8.1 Rate Equations

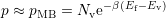

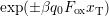

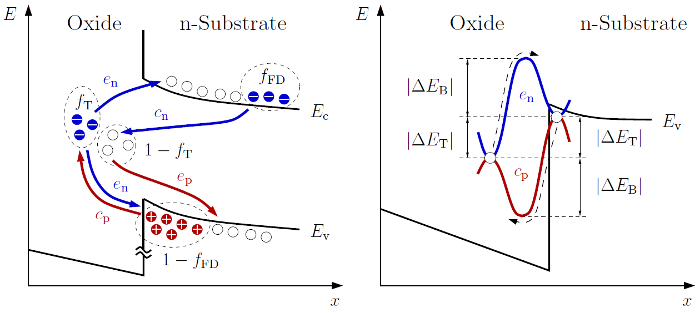

Based on the existence of oxide defects and the band-to-trap transition

possibilities, depicted in Fig. 8.1, already a single defect system has to consider

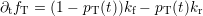

all transitions originating from various band states. This means that the whole

conduction or valence band has to be considered, instead of only  or

or

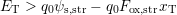

. On the basis of the statistical description of the recombination of

electrons and holes under the release of energy in terms of lattice vibrations

(Shockley-Read-Hall theory [122]), the determination of effective rates in and out

of a specific defect system is possible. The corresponding rate equations are

. On the basis of the statistical description of the recombination of

electrons and holes under the release of energy in terms of lattice vibrations

(Shockley-Read-Hall theory [122]), the determination of effective rates in and out

of a specific defect system is possible. The corresponding rate equations are

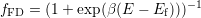

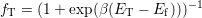

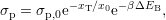

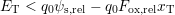

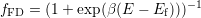

with the trap occupancy in the oxide  and the Fermi-Dirac distribution

and the Fermi-Dirac distribution  ,

which represents the probability of an occupied quantum state in the substrate.

Since the Fermi-Dirac distribution is valid in thermal equilibrium and still a very

good approximation during BTI, as there is nearly no channel current

[129, 130], the distributions write as

,

which represents the probability of an occupied quantum state in the substrate.

Since the Fermi-Dirac distribution is valid in thermal equilibrium and still a very

good approximation during BTI, as there is nearly no channel current

[129, 130], the distributions write as  and

and

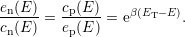

. The quantities

. The quantities  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  stand for

the coefficients of electron capture, electron emission, hole emission, and hole

capture. The density of states (DOS) is split into a conduction band part

stand for

the coefficients of electron capture, electron emission, hole emission, and hole

capture. The density of states (DOS) is split into a conduction band part  and a valence band part

and a valence band part  .

.

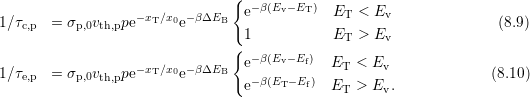

Assuming detailed balance [122], which means that each process is balanced

by its reverse process, both rates have to equal within (8.1) and (8.2). This

yields

| (8.3) |

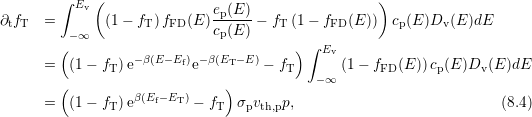

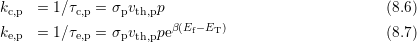

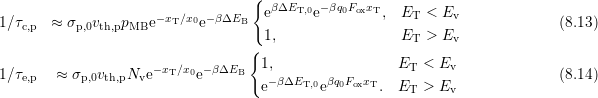

Combining (8.3) with (8.2)

and evaluating the integral finally gives the capture time constant  of the

holes

of the

holes

with the cross section  and thermal velocity

and thermal velocity  of the holes with density

of the holes with density

. The term outside the brackets can be identified as the capture rate, which

can be seen when (8.4) is compared to the simple rate equation of a two-state

defect

. The term outside the brackets can be identified as the capture rate, which

can be seen when (8.4) is compared to the simple rate equation of a two-state

defect

| (8.5) |

with the rate  to fill the defect at

to fill the defect at  and

and  for the reverse rate.

Furthermore,

for the reverse rate.

Furthermore,  gives the probability that the defect is actually filled.

Consequently, the capture and emission rates can be written as

gives the probability that the defect is actually filled.

Consequently, the capture and emission rates can be written as

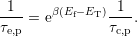

or as the relation

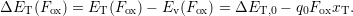

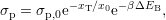

In addition to a tunneling coefficient of  to account for the oxide

trap depth after [121], the cross section is considered to be thermally activated

with a bias independent barrier

to account for the oxide

trap depth after [121], the cross section is considered to be thermally activated

with a bias independent barrier  [124]. Putting these assumptions together

yields

[124]. Putting these assumptions together

yields

| (8.8) |

with a constant prefactor  [131, 124]. With the knowledge that whether the

defect level lies below or above

[131, 124]. With the knowledge that whether the

defect level lies below or above  , different barriers are obtained after

Fig. 8.1, equations (8.6) to (8.8) are now used to calculate the capture rates

, different barriers are obtained after

Fig. 8.1, equations (8.6) to (8.8) are now used to calculate the capture rates

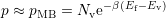

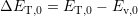

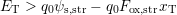

As thermal equilibrium is assumed and the density of states is low enough to rule

out quantum effects, the Fermi-Dirac-distribution can be replaced by the

Maxwell–Boltzmann-distribution [10]

| (8.11) |

with  as effective valence band weight,

as effective valence band weight,

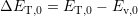

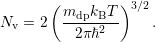

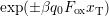

The trapping barrier  can further be written as a superposition of the

energy distance during flatband

can further be written as a superposition of the

energy distance during flatband  and the applied field

and the applied field  which changes the relative barrier between semiconductor and oxide, cf. Fig. 8.1

(right) and Fig. 8.2 (right)

which changes the relative barrier between semiconductor and oxide, cf. Fig. 8.1

(right) and Fig. 8.2 (right)

| (8.12) |

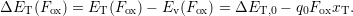

With the help of (8.11) and (8.12) the time constants in (8.9) and (8.10) finally

read as

At first only the part of (8.13) and (8.14), which depends on the relative position

of  to

to  is discussed. The temperature dependence here is dominated by

the thermal barrier

is discussed. The temperature dependence here is dominated by

the thermal barrier  . While the barrier

. While the barrier  determines hole capture

when

determines hole capture

when  holds, the barrier

holds, the barrier  contributes to hole emission only

when

contributes to hole emission only

when  . So the barriers are either relevant for

. So the barriers are either relevant for  or

or  and do not

affect both rates. This is due to the relative position of the energetic defect level

and its reservoir, as depicted in Fig. 8.1 (left). When looking at the term

and do not

affect both rates. This is due to the relative position of the energetic defect level

and its reservoir, as depicted in Fig. 8.1 (left). When looking at the term

, it can be seen that the applied field either lowers

or rises the barrier, but again the field dependence is only included in

either

, it can be seen that the applied field either lowers

or rises the barrier, but again the field dependence is only included in

either  or

or  . Additional bias dependencies arise from the surface

hole concentration, especially below

. Additional bias dependencies arise from the surface

hole concentration, especially below  , and the tunneling coefficient

[130].

, and the tunneling coefficient

[130].

In a typical BTI stress/relaxation sequence all defects are in thermal

equilibrium prior to stress. Due to stress the Fermi level  is shifted

below

is shifted

below  . For defects with

. For defects with  the resulting barrier

the resulting barrier  can

only be balanced by the

can

only be balanced by the  term in (8.13). After (8.12) this means

that energetically deeper defects also need to be located deeper in the

oxide in order to become charged during stress, i.e. only defects with

term in (8.13). After (8.12) this means

that energetically deeper defects also need to be located deeper in the

oxide in order to become charged during stress, i.e. only defects with

, where

, where  denotes the potential at the interface,

are accessible during stress [130]. When the stress is completely removed,

denotes the potential at the interface,

are accessible during stress [130]. When the stress is completely removed,  is shifted back above

is shifted back above  and the previously charged defects will by

moved back below

and the previously charged defects will by

moved back below  . According to (8.14) they can be emptied over a

small barrier if there is any. Thereby accessible oxide defects now feature

. According to (8.14) they can be emptied over a

small barrier if there is any. Thereby accessible oxide defects now feature

during relaxation [130]. Thus, the exact defect level

is not of particular interest for the capture and emission process.

during relaxation [130]. Thus, the exact defect level

is not of particular interest for the capture and emission process.  only has to lie inside the accessible energy region, i.e. above

only has to lie inside the accessible energy region, i.e. above  for

stress and below

for

stress and below  for relaxation. This means that the conditional

part of (8.13) and (8.14) only exhibits a small temperature and field

dependence.

for relaxation. This means that the conditional

part of (8.13) and (8.14) only exhibits a small temperature and field

dependence.

It is important to realize that it is the thermal barrier  in (8.13) and

(8.14) introduced by Kirton and Uren, which gives the required temperature

dependence, though this dependence is not fully correct, as will be shown

later. To first order, the capture

in (8.13) and

(8.14) introduced by Kirton and Uren, which gives the required temperature

dependence, though this dependence is not fully correct, as will be shown

later. To first order, the capture  and emission times

and emission times  of the

defects are determined by

of the

defects are determined by  and

and  , making another fact visible:

, making another fact visible:

and

and  are correlated, while measurement results determining

these times during BTI revealed uncorrelated behavior [111, 116]. This

rules out the possibility of describing oxide defects by an extended SRH

theory.

are correlated, while measurement results determining

these times during BTI revealed uncorrelated behavior [111, 116]. This

rules out the possibility of describing oxide defects by an extended SRH

theory.

or

or

. On the basis of the statistical description of the recombination of

electrons and holes under the release of energy in terms of lattice vibrations

(Shockley-Read-Hall theory [122]), the determination of effective rates in and out

of a specific defect system is possible. The corresponding rate equations are

. On the basis of the statistical description of the recombination of

electrons and holes under the release of energy in terms of lattice vibrations

(Shockley-Read-Hall theory [122]), the determination of effective rates in and out

of a specific defect system is possible. The corresponding rate equations are

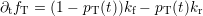

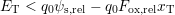

![∫ ∞

∂tfT = [(1 − fT) fFD(E)cn(E )− fT (1 − fFD(E ))en(E)]Dc (E )dE (8.1 )

∫Ec

Ev

= [(1− fT)fFD(E )ep(E )− fT (1− fFD (E))cp(E )]Dv (E )dE, (8.2 )

−∞](diss1617x.png)

and the Fermi-Dirac distribution

and the Fermi-Dirac distribution  ,

which represents the probability of an occupied quantum state in the substrate.

Since the Fermi-Dirac distribution is valid in thermal equilibrium and still a very

good approximation during BTI, as there is nearly no channel current

,

which represents the probability of an occupied quantum state in the substrate.

Since the Fermi-Dirac distribution is valid in thermal equilibrium and still a very

good approximation during BTI, as there is nearly no channel current

and

and

. The quantities

. The quantities  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  stand for

the coefficients of electron capture, electron emission, hole emission, and hole

capture. The density of states (DOS) is split into a conduction band part

stand for

the coefficients of electron capture, electron emission, hole emission, and hole

capture. The density of states (DOS) is split into a conduction band part  and a valence band part

and a valence band part  .

.

and an

additional barrier

and an

additional barrier  .

.

of the

holes

of the

holes

and thermal velocity

and thermal velocity  of the holes with density

of the holes with density

. The term outside the brackets can be identified as the capture rate, which

can be seen when (8.4) is compared to the simple rate equation of a two-state

defect

. The term outside the brackets can be identified as the capture rate, which

can be seen when (8.4) is compared to the simple rate equation of a two-state

defect

to fill the defect at

to fill the defect at  and

and  for the reverse rate.

Furthermore,

for the reverse rate.

Furthermore,  gives the probability that the defect is actually filled.

Consequently, the capture and emission rates can be written as

gives the probability that the defect is actually filled.

Consequently, the capture and emission rates can be written as

to account for the oxide

trap depth after

to account for the oxide

trap depth after

, different barriers are obtained after

Fig.

, different barriers are obtained after

Fig.

as effective valence band weight,

as effective valence band weight,

can further be written as a superposition of the

energy distance during flatband

can further be written as a superposition of the

energy distance during flatband  and the applied field

and the applied field  which changes the relative barrier between semiconductor and oxide, cf. Fig.

which changes the relative barrier between semiconductor and oxide, cf. Fig.

to

to  is discussed. The temperature dependence here is dominated by

the thermal barrier

is discussed. The temperature dependence here is dominated by

the thermal barrier  . While the barrier

. While the barrier  determines hole capture

when

determines hole capture

when  holds, the barrier

holds, the barrier  contributes to hole emission only

when

contributes to hole emission only

when  . So the barriers are either relevant for

. So the barriers are either relevant for  or

or  and do not

affect both rates. This is due to the relative position of the energetic defect level

and its reservoir, as depicted in Fig. 8.1 (left). When looking at the term

and do not

affect both rates. This is due to the relative position of the energetic defect level

and its reservoir, as depicted in Fig. 8.1 (left). When looking at the term

, it can be seen that the applied field either lowers

or rises the barrier, but again the field dependence is only included in

either

, it can be seen that the applied field either lowers

or rises the barrier, but again the field dependence is only included in

either  or

or  . Additional bias dependencies arise from the surface

hole concentration, especially below

. Additional bias dependencies arise from the surface

hole concentration, especially below  , and the tunneling coefficient

, and the tunneling coefficient

is shifted

below

is shifted

below  . For defects with

. For defects with  the resulting barrier

the resulting barrier  can

only be balanced by the

can

only be balanced by the  term in (

term in ( , where

, where  denotes the potential at the interface,

are accessible during stress

denotes the potential at the interface,

are accessible during stress  is shifted back above

is shifted back above  and the previously charged defects will by

moved back below

and the previously charged defects will by

moved back below  . According to (

. According to ( during relaxation

during relaxation  only has to lie inside the accessible energy region, i.e. above

only has to lie inside the accessible energy region, i.e. above  for

stress and below

for

stress and below  for relaxation. This means that the conditional

part of (

for relaxation. This means that the conditional

part of ( in (

in ( and emission times

and emission times  of the

defects are determined by

of the

defects are determined by  and

and  , making another fact visible:

, making another fact visible:

and

and  are correlated, while measurement results determining

these times during BTI revealed uncorrelated behavior

are correlated, while measurement results determining

these times during BTI revealed uncorrelated behavior