:

: The last section has been devoted to the possible physical explanations for the charge trapping process in NBTI. The involved mechanisms, such as quantum mechanical tunneling for instance, are characterized by their stochastic nature. This means that one must deal with probabilities instead of pre-determined transition times for the trapping events. Such problems can be best handled within the framework of homogeneous continuous-time Markov chain theory [131], which rests on the assumption that the transition rates do not depend on the past of the investigated system.

The continuous time Markov chain theory presumes a set of discrete states

:

:

are the time-dependent occupation probabilities, which fulfill the

normalization condition

are the time-dependent occupation probabilities, which fulfill the

normalization condition

equals unity. The time-dependent probability

equals unity. The time-dependent probability  for a transition from state

for a transition from state

to state

to state  can be formulated as where

can be formulated as where  denotes the transition rate belonging to

denotes the transition rate belonging to  . The time evolution of

the system can be described by the first-order partial differential equation

The above equation is referred to as the Master or rate equation and controls the

time-dependent occupation probabilities. The first term on the right-hand side

represents the transitions

. The time evolution of

the system can be described by the first-order partial differential equation

The above equation is referred to as the Master or rate equation and controls the

time-dependent occupation probabilities. The first term on the right-hand side

represents the transitions  while the second term stands for the opposite

direction. With the definition

while the second term stands for the opposite

direction. With the definition

denotes the matrix belonging to the elements

denotes the matrix belonging to the elements  . The solution of

equation (3.19) is given by

. The solution of

equation (3.19) is given by

vanishes and the equilibrium

occupation probabilities

vanishes and the equilibrium

occupation probabilities  must satisfy

must satisfy

In the case of charge trapping, a single defect is represented by one vector  .

When considering a large ensemble of defects, the stochastic behavior vanishes and

.

When considering a large ensemble of defects, the stochastic behavior vanishes and

and

and  can be replaced by their corresponding expectation values

can be replaced by their corresponding expectation values

and

and  , respectively. Then the equations (3.19) and (3.22) read

, respectively. Then the equations (3.19) and (3.22) read

When applying Markov theory to charge trapping in NBTI, each state must be

assigned to a certain configuration and a certain charge state of a defect. The rates

linking the states

linking the states  and

and  must be related to certain defect transitions, such

as charge transfer reactions or thermally activated rearrangements of the defect

structure. The trapping dynamics are then governed by equation (3.23), which must

be solved as a function of time. The details of the applied numerical procedures are

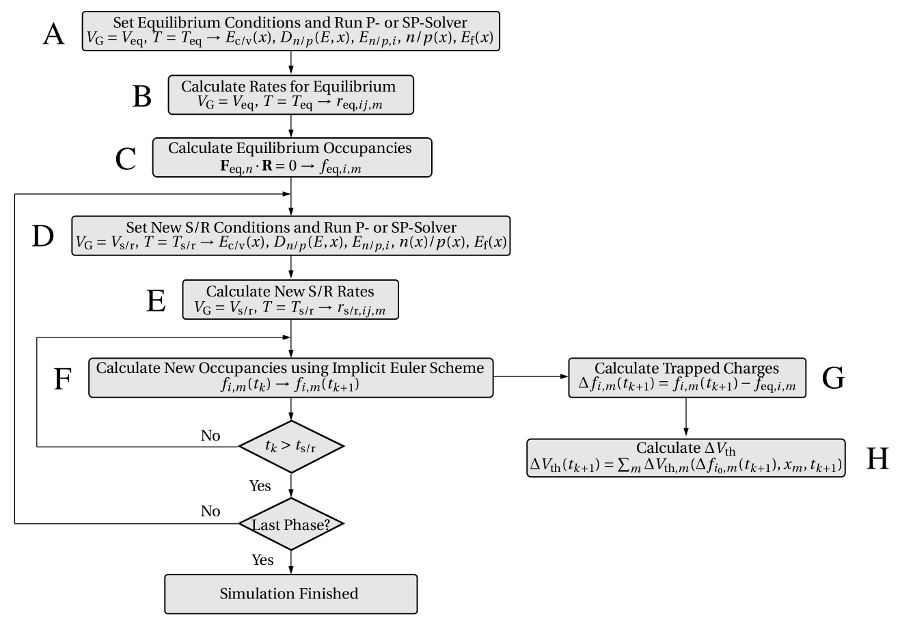

outlined in Fig. 3.2.

must be related to certain defect transitions, such

as charge transfer reactions or thermally activated rearrangements of the defect

structure. The trapping dynamics are then governed by equation (3.23), which must

be solved as a function of time. The details of the applied numerical procedures are

outlined in Fig. 3.2.

,

,  ) are

calculated in steps A, B, and C. During one stress or relaxation cycle, the band

edges (D) and the transition rates (E) must be determined at first. Then the

corresponding the time-dependent occupations (F) and the resulting threshold

voltage shift (G,F) are evaluated at each time step

) are

calculated in steps A, B, and C. During one stress or relaxation cycle, the band

edges (D) and the transition rates (E) must be determined at first. Then the

corresponding the time-dependent occupations (F) and the resulting threshold

voltage shift (G,F) are evaluated at each time step  . This complete cycle

must be performed for each stress or relaxation phase.

. This complete cycle

must be performed for each stress or relaxation phase.Before the real device is subject to stress, the device is assumed to be in equilibrium.

The corresponding band diagram is computed by a P/SP-solver (A) for the

equilibrium conditions  and

and  . Based on this information, the

transition rates

. Based on this information, the

transition rates  (B) can be evaluated for each defect

(B) can be evaluated for each defect  . With the

rates

. With the

rates  at hand, the equilibrium occupation probabilities

at hand, the equilibrium occupation probabilities  are calculated using the equation (3.24) and must be subsequently stored

(C). When stress sets in, the gate voltage

are calculated using the equation (3.24) and must be subsequently stored

(C). When stress sets in, the gate voltage  and the temperature

and the temperature  are

changed to

are

changed to  and

and  , respectively. Since this alters the band diagram and

in consequence the transition rates

, respectively. Since this alters the band diagram and

in consequence the transition rates  , the S/SP-solver step (D) and

the calculation of the rates (E) must be repeated. Then the implicit Euler

method is employed for the numerical time integration of equation (3.23).

This iteration scheme must be continued until the end of the stress time

, the S/SP-solver step (D) and

the calculation of the rates (E) must be repeated. Then the implicit Euler

method is employed for the numerical time integration of equation (3.23).

This iteration scheme must be continued until the end of the stress time

has been reached. At each

has been reached. At each  , the change in the defect occupancies

, the change in the defect occupancies

(G) and the corresponding threshold voltage shift

(G) and the corresponding threshold voltage shift  (H) are

computed. With the beginning of the relaxation phase,

(H) are

computed. With the beginning of the relaxation phase,  and

and  are

modified again and the whole iteration loop including the steps D, E, F, G, and

H must be repeated. This can be continued for several stress/relaxation

cycles with different stress/relaxation conditions. The steps E, F, and G

of numerical procedure in Fig. 3.2 must be repeated for each individual

defect, where the calculation of the rates requires most of the computation

time.

are

modified again and the whole iteration loop including the steps D, E, F, G, and

H must be repeated. This can be continued for several stress/relaxation

cycles with different stress/relaxation conditions. The steps E, F, and G

of numerical procedure in Fig. 3.2 must be repeated for each individual

defect, where the calculation of the rates requires most of the computation

time.

For the evaluation of  , the charge sheet approximation is employed.

, the charge sheet approximation is employed.

and

and  are the trap depth and the thickness of the dielectric, respectively. The

above expression gives the threshold voltage shift

are the trap depth and the thickness of the dielectric, respectively. The

above expression gives the threshold voltage shift  due to a single trap

due to a single trap  in

the ‘charged’ state

in

the ‘charged’ state  . It is noted that the term in the parentheses of equation (3.25)

accounts for the trap depth dependence of

. It is noted that the term in the parentheses of equation (3.25)

accounts for the trap depth dependence of  according to which

traps closer to the interface have a larger impact on the threshold voltage.

However, there also exists a strong dependence on the lateral location of the

traps, totally neglected in the above equation. Recall in this context that

the

according to which

traps closer to the interface have a larger impact on the threshold voltage.

However, there also exists a strong dependence on the lateral location of the

traps, totally neglected in the above equation. Recall in this context that

the  steps in the TDDS measurements have also been caused by single

charged traps. The wide variations of these steps have been ascribed to the

position of the traps relative to the current percolation path and follow an

exponential distribution according to an investigation carried out by Kazcer et

al. [50]. This issue has been intensively studied under the name random

dopant fluctuations [132, 133, 134, 50] and gained large interest due to its

serious influence on the lifetime projection. For instance, the charging of one

defect can even produce step heights in the threshold voltage beyond

steps in the TDDS measurements have also been caused by single

charged traps. The wide variations of these steps have been ascribed to the

position of the traps relative to the current percolation path and follow an

exponential distribution according to an investigation carried out by Kazcer et

al. [50]. This issue has been intensively studied under the name random

dopant fluctuations [132, 133, 134, 50] and gained large interest due to its

serious influence on the lifetime projection. For instance, the charging of one

defect can even produce step heights in the threshold voltage beyond  ,

which already violates typical lifetime criteria. By contrast, the charge sheet

approximation rests on the assumption that a trapped charge is distributed over the

whole plane parallel to the interface. Therefore, variations in the threshold

voltage shift due to random dopant fluctuations remain unconsidered in this

approximation.

,

which already violates typical lifetime criteria. By contrast, the charge sheet

approximation rests on the assumption that a trapped charge is distributed over the

whole plane parallel to the interface. Therefore, variations in the threshold

voltage shift due to random dopant fluctuations remain unconsidered in this

approximation.

Small-area devices often contain only a handful of defects. Then the steps B, C, E, F, G, and H can be performed at computationally feasible costs. But since the calculation time increases with the number of defects, the simulation of large-area devices can become time-consuming. In order to reduce computation time for these simulations, a certain number of defects with similar properties are grouped together and replaced by one representative trap. This approach implies that the channel area covers several defects with similar properties including the trap level and the spatial location among others1. Furthermore, it is important to note here that the value of trap density is often quite inaccurate and can differ by some orders of magnitude. Therefore, the number of traps must be treated as a variable in the simulations. This means that the calculated degradation curves can be scaled to the experimental data in order to achieve reasonable agreement of the simulations with the measurements.