|  |  |

While the Lagrangian formalism already provides extensive capabilities to handle elaborate problems, further refinement is possible resulting in the so called phase space, which also makes concepts available, which can even be carried beyond the confines of classical mechanics.

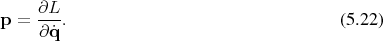

Motivated by the aim to find a simpler, more symmetric expression of the equation of motion as given in Equation 5.14, it is fruitful to utilize the fact from the settings of the Lagrangian in Equation 5.10 and Equation 5.12, from which follows that the momentum is expressible as

using a

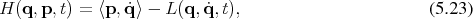

Legendre map (Definition 53) results in

using a

Legendre map (Definition 53) results in

, the Hamiltonian is a function on the co-tangent bundle

, the Hamiltonian is a function on the co-tangent bundle  ,

which is called the phase space.

,

which is called the phase space.

of an

of an  dimensional base manifold into a symplectic manifold (Definition 82)

of dimension

dimensional base manifold into a symplectic manifold (Definition 82)

of dimension  . Among the great strengths of the Hamilton formalism is the fact that

Hamilton’s equations can be expressed using this geometric structure inherent to the phase

space.

. Among the great strengths of the Hamilton formalism is the fact that

Hamilton’s equations can be expressed using this geometric structure inherent to the phase

space.

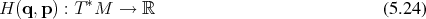

The symplectic nature of the manifold used ensures that it is always possible, as asserted by Definition 84, to find coordinates such that

called canonical coordinates.

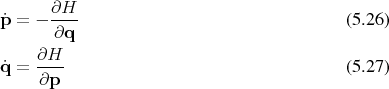

The equations of motion as observed in the Lagrangian case take on the simpler, almost symmetric form

(Definition 62) along with

associated integral curves

(Definition 62) along with

associated integral curves  (Definition 63), which all taken together define the phase flow

(Definition 63), which all taken together define the phase flow

(Definition 67). This phase flow is a symplectomorphism (Definition 83), thus leaving the

symplectic structure (Definition 81) of the manifold invariant.

(Definition 67). This phase flow is a symplectomorphism (Definition 83), thus leaving the

symplectic structure (Definition 81) of the manifold invariant.

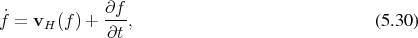

The vector field due to the Hamiltonian  can be expressed utilizing the geometrical structure (compare

Equation 4.162) inherent to the phase space.

can be expressed utilizing the geometrical structure (compare

Equation 4.162) inherent to the phase space.

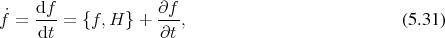

changes. In case of a function

changes. In case of a function  , which measures a quantity of interest in the phase

space

, which measures a quantity of interest in the phase

space

due to the Hamiltonian and its own dependence on the

parameter is then simply given by

due to the Hamiltonian and its own dependence on the

parameter is then simply given by

(see Equation 4.109),

which is usually given explicitly using the Poisson bracket (Definition 86) in the form

(see Equation 4.109),

which is usually given explicitly using the Poisson bracket (Definition 86) in the form

|  |  |