|  |  |

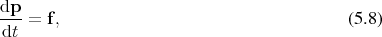

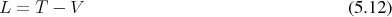

As Newton’s ideas and methods were adopted and applied to address problems of increasing sophistication its limits were also made apparent by the increase in the complexity of the used notation. Consequently, further development had the goal of addressing these shortcomings by simplifying calculations and establishing the foundations for a wider variety of treatable problems. Therefore, computational methods and notations to handle the increasing intricacies of the posed problems have been developed by Euler [64], Laplace [85] and Lagrange [86], without altering the fundamentals or the nature of Newton’s world. Where Newton’s description focuses on forces and accelerations using second order differential equations, the Lagrangian formulation recasts them as a set of first order differential equations. It does so by redirecting attention from the explicit treatment of forces and accelerations to expressions linked to energy. Starting from an expression for Newton’s second law

is linkable to kinetic energy

is linkable to kinetic energy  and expressible as

and expressible as

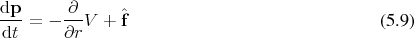

Based on the Lagrangian, a motion takes the form

and

and  , where

, where  corresponds to a base

manifold

corresponds to a base

manifold  ,

,  is from the tangent space

is from the tangent space  Thus this description can be summarized

to take place in the tangent bundle

Thus this description can be summarized

to take place in the tangent bundle  . Where previously a location, a velocity and an

acceleration were required, it is now sufficient to provide a point in this tangent bundle,

called the configuration space. This does not change the Galilean structure of the world,

however.

. Where previously a location, a velocity and an

acceleration were required, it is now sufficient to provide a point in this tangent bundle,

called the configuration space. This does not change the Galilean structure of the world,

however.

A trajectory which is used to describe a motion within the manifold  (Definition 35) may be

associated with a curve (Definition 45) in the tangent bundle

(Definition 35) may be

associated with a curve (Definition 45) in the tangent bundle  (Definition 52) of

(Definition 52) of  using a

lift (Definition 26). Among all of the possible choices to lift a curve

using a

lift (Definition 26). Among all of the possible choices to lift a curve  , the one of the form

, the one of the form

The curve to be lifted connects a starting point to an end point, thus changing the description from an initial value problem, to a boundary value problem. In order to appreciate the geometric nature of Lagrange’s formalism a short exploration of the concepts behind the distance of two points in a more traditional geometric setting is explored.

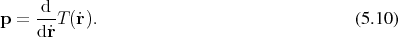

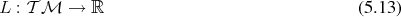

Using the clearly geometric construction presented in Section 4.8, with the Lagrangian  taking the

place of the metric field, it is possible to evaluate the Lagrangian along a lifted curve and, again using

the notion of a curve integral (Definition 95), assign values, called actions, to sections of any curve in

the following fashion

taking the

place of the metric field, it is possible to evaluate the Lagrangian along a lifted curve and, again using

the notion of a curve integral (Definition 95), assign values, called actions, to sections of any curve in

the following fashion

![∫ ∫ ∫

S = [t,t]L (¯γ (t),t)dt = [t,t]L(γ, ˙γ,t)dt = [t ,t]L (q, ˙q,t)dt, (5 .16)

0 1 0 1 0 1](whole786x.png)

and

and  correspond to the points

correspond to the points  and

and  as indicated in Figure 5.2. In

mimicking the definition of distance, this allows to distinguish the various trajectories from each other,

thus providing a selection criterion in the form of the extrema which can be derived using

a simple homotopy (Definition 32) for variation, as can be shown in a short calculation.

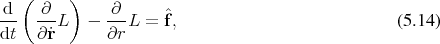

as indicated in Figure 5.2. In

mimicking the definition of distance, this allows to distinguish the various trajectories from each other,

thus providing a selection criterion in the form of the extrema which can be derived using

a simple homotopy (Definition 32) for variation, as can be shown in a short calculation.

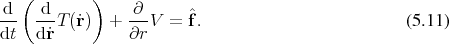

![d ∫

S = --|s=0 L(γ + sη, ˙γ + s˙η)dt = 0 (5.17)

ds [t0,t1]](whole791x.png)

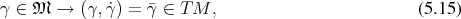

![∫ ∫ [ ]

S=d| L(α,α˙)dt = -∂-L(γ, ˙γ)∂γ-+ ∂--L(γ,γ˙)∂˙γ- dt = 0. (5.19)

dss=0 [t0,t1] [t0,t1] ∂γ ∂t ∂˙γ ∂t](whole793x.png)

![∫ ∂ ∂˙γ ∫ ∂ ( ∂ ) ∂γ

---L(γ,γ˙)---dt = − --- --L (γ, ˙γ) --dt, (5 .20)

[t0,t1]∂γ˙ ∂t [t0,t1]∂t ∂˙γ ∂t](whole794x.png)

![∫ [ ( ) ]

∂ ∂ ∂

∂t- ∂γ˙L(γ, ˙γ) − ∂-γL (γ, ˙γ) ˙γdt = 0, (5 .21)

[t0,t1]](whole795x.png)

, which pass through

the given points

, which pass through

the given points  and

and  , as shown in Figure 5.2, the actual realization can be found by the

minimization of the action defined in Equation 5.16 as in this case the equations of motion in the form

of the Euler-Lagrange Equation are met.

, as shown in Figure 5.2, the actual realization can be found by the

minimization of the action defined in Equation 5.16 as in this case the equations of motion in the form

of the Euler-Lagrange Equation are met.

|  |  |