Next: 2 Estimating the Void

Up: 6 Simulation Results

Previous: 6 Simulation Results

1 Two-Dimensional Void Evolution

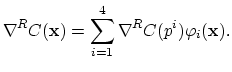

In all following simulations a circle was chosen as initial void shape. The

resolution of the parameter  profile can be manipulated by setting

parameter

profile can be manipulated by setting

parameter  which is the mean number of triangles across

the void-metal interface. On Fig. 4.8 initial grids for

which is the mean number of triangles across

the void-metal interface. On Fig. 4.8 initial grids for  and

and

are presented.

are presented.

Figure 4.8:

Initial grid refinements.

|

|

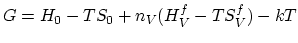

We consider a two-dimensional, stress free, electricaly conducting

interconnect via.

Figure 4.9:

Interconnect via with initial void.

|

constant voltage is applied between points

constant voltage is applied between points  and

and

(Figure 4.9). At

(Figure 4.9). At  a refractory

layer is assumed. Because of geometrical

reasons there is current crowding in the adjacencies of the corners

a refractory

layer is assumed. Because of geometrical

reasons there is current crowding in the adjacencies of the corners

and

and  .

The analytical solution of equation (4.52) has at these points

actually a singularity [90,76].

.

The analytical solution of equation (4.52) has at these points

actually a singularity [90,76].

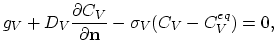

High electrical field gradients in the area around the corner points

increase overall error of the finite element scheme for the equation

(4.52) which is overcome by applying an additional refinement of

the basic mesh  according to the local value of the electric

field gradient (Figure 4.10).

according to the local value of the electric

field gradient (Figure 4.10).

Figure 4.10:

Profile of the current density (in  ) at the corners of

the interconnect.

) at the corners of

the interconnect.

|

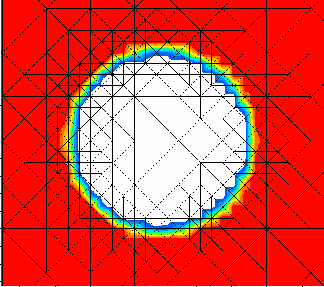

A fine triangulated belt area which is attached to the void-metal

interface at the initial simulations step follows the

interfacial area throughout the simulations whereby the interconnect area

outside the interface is coarsened to the level of the basic grid

(Figure 4.11).

(Figure 4.11).

Figure 4.11:

Refined grid around the void in the proximity of the

interconnect corner.

|

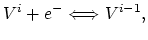

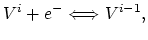

Figure 4.12:

Void evolving through interconnect in the electric current direction

|

Figure 4.13:

Time dependent resistance change during void evolution for

the different initial void radius  .

.

|

In our simulations a void evolving through the straight part of the

interconnect geometry exhibits similar shape changes as observed in earlier models [60,59]. There is also no significant

fluctuation of the resistance during this period of interconnect

evolution.

The situation changes when the void evolves in the

proximity of the interconnect corner (Figure 4.12).

Due to current crowding in this

area the influence of the electromigration force on the material transport on the void surface

is more pronounced than the chemical potential gradient. This

unbalance leads to higher asymmetry in the void shape then observed in

the straight part of the interconnect (Figure 4.12).

A void evolving in the proximity of the interconnect corner causes significant

fluctuations in the interconnect resistance due to void asymmetry and

position.

The resistance change shows a charasteristic

profile with two peaks and a valley (Figure 4.13). The extremes are

more pronounced for the larger initial voids.

The capability of the applied adaptation scheme is also presented in the

simulation of void collision with the interconnect refractory layer (Figure 4.14).

The time step  for the numerical scheme

(4.55)-(4.58) is fitted at the simulations begin taking into account

inverse proportionality of the speed of the evolving void-metal interface to the initial void radius [60]:

for the numerical scheme

(4.55)-(4.58) is fitted at the simulations begin taking into account

inverse proportionality of the speed of the evolving void-metal interface to the initial void radius [60]:

|

(272) |

Figure 4.14:

Grid adaptation in the case of void collision with the refractory layer.

|

is the characteristical length of via geometry.

An appropriate choice of the time step ensures that the evolving

void-metal interface will stay inside the fine grid belt during the

simulation.

The dynamics of the evolving void-metal interface simulated with a

the presented numerical scheme complies with the mass conservation law,

the void area (where

is the characteristical length of via geometry.

An appropriate choice of the time step ensures that the evolving

void-metal interface will stay inside the fine grid belt during the

simulation.

The dynamics of the evolving void-metal interface simulated with a

the presented numerical scheme complies with the mass conservation law,

the void area (where  ) remains approximately the same during

the whole simulation.

Notable area deviations during the simulation appear only, if a

relatively large factor

) remains approximately the same during

the whole simulation.

Notable area deviations during the simulation appear only, if a

relatively large factor  has been chosen.

As scaling length we took

has been chosen.

As scaling length we took  and for the initial void radius

and for the initial void radius

,

,

, and

, and

.

Our simulations have shown that for all considered initial void radii,

voids follow the electric current direction (Figure 4.13) and do not transform in slit or wedge like formations which

have been found to be a main cause for a complete interconnect

failure [54].

Already with

.

Our simulations have shown that for all considered initial void radii,

voids follow the electric current direction (Figure 4.13) and do not transform in slit or wedge like formations which

have been found to be a main cause for a complete interconnect

failure [54].

Already with

good approximations are achieved.

The number of elements on the cross section of the void-metal

interface was chosen between 6 and 10 with the interface width of

good approximations are achieved.

The number of elements on the cross section of the void-metal

interface was chosen between 6 and 10 with the interface width of

.

.

Next: 2 Estimating the Void

Up: 6 Simulation Results

Previous: 6 Simulation Results

J. Cervenka: Three-Dimensional Mesh Generation for Device and Process Simulation

![]() profile can be manipulated by setting

parameter

profile can be manipulated by setting

parameter ![]() which is the mean number of triangles across

the void-metal interface. On Fig. 4.8 initial grids for

which is the mean number of triangles across

the void-metal interface. On Fig. 4.8 initial grids for ![]() and

and

![]() are presented.

are presented.