depending on gate bias and

temperature. Long term extrapolation does not only allow lifetime projection relevant

for industrial purposes but also should be viewed as a touchstone for subsequent

modeling attempts.

depending on gate bias and

temperature. Long term extrapolation does not only allow lifetime projection relevant

for industrial purposes but also should be viewed as a touchstone for subsequent

modeling attempts.

Before embarking on detailed physical models, the focus is now put on a

phenomenological understanding of NBTI. In this respect, special attention is put on

the functional form of the time evolution of  depending on gate bias and

temperature. Long term extrapolation does not only allow lifetime projection relevant

for industrial purposes but also should be viewed as a touchstone for subsequent

modeling attempts.

depending on gate bias and

temperature. Long term extrapolation does not only allow lifetime projection relevant

for industrial purposes but also should be viewed as a touchstone for subsequent

modeling attempts.

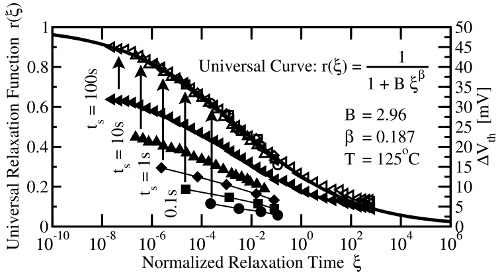

Grasser et al. [24] recognized that the recorded threshold voltage curves follow the same pattern at different stress temperatures and voltages. Therefore, these curves can be scaled so that they overlap for the stress and the relaxation phase. Mathematically, this can be described by

represents the temperature (

represents the temperature ( ) and oxide field

(

) and oxide field

( ) dependence, which is best approximated by

) dependence, which is best approximated by

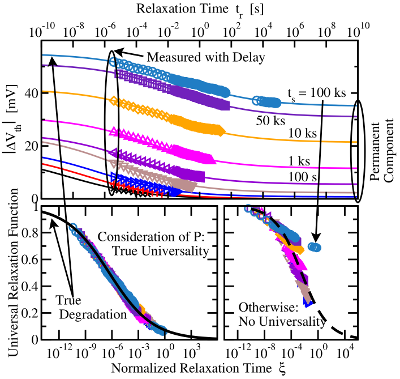

mimics a universally valid shape of the threshold voltage curves. A

series of stress sequences for different temperatures are depicted in Fig. 1.3 in order

to illustrate the common pattern of the threshold voltage data. As a proof for

scalability, all curves line up to one curve by dividing them by their corresponding

mimics a universally valid shape of the threshold voltage curves. A

series of stress sequences for different temperatures are depicted in Fig. 1.3 in order

to illustrate the common pattern of the threshold voltage data. As a proof for

scalability, all curves line up to one curve by dividing them by their corresponding

. As demonstrated in Fig. 1.3, the initial part of the stress phase shows a

logarithmic behavior up to a stress time

. As demonstrated in Fig. 1.3, the initial part of the stress phase shows a

logarithmic behavior up to a stress time  while the subsequent part follows

a power-law with an exponent of

while the subsequent part follows

a power-law with an exponent of  afterwards. The stress phase [24] can be

expressed as

afterwards. The stress phase [24] can be

expressed as

denotes the first stress measurement point. However, Huard [57] reported

that, for some devices, the scalability property is violated for the long term

degradation with stress times larger

denotes the first stress measurement point. However, Huard [57] reported

that, for some devices, the scalability property is violated for the long term

degradation with stress times larger  . Depending on the details of the

fabrication process, the long term part has a scaling factor, which is estimated as

. Depending on the details of the

fabrication process, the long term part has a scaling factor, which is estimated as

being an activation energy of

being an activation energy of  .

.

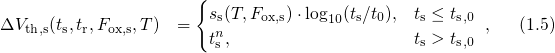

) applying the extended MSM (eMSM)

scheme [25, 26]. In this method, the investigated device is subject to

exponentially growing stress intervals (

) applying the extended MSM (eMSM)

scheme [25, 26]. In this method, the investigated device is subject to

exponentially growing stress intervals ( ) with interruptions of

) with interruptions of  (visible as spikes in the plots). During stress, the OTF technique is employed,

in which the degradation of threshold voltage is estimated using the expression

(visible as spikes in the plots). During stress, the OTF technique is employed,

in which the degradation of threshold voltage is estimated using the expression

. During the short relaxation periods,

the drain current is converted to the threshold voltage using a initially recorded

. During the short relaxation periods,

the drain current is converted to the threshold voltage using a initially recorded

curve. Right: The same data as in the left figure, where each curve

is multiplied with a suitably chosen factor. All curves share the same shape as

proven by the nearly perfect overlap. Note that the degradation lost during the

short stress interruptions is restored within less than one decade and thus does

not affect the extracted exponent

curve. Right: The same data as in the left figure, where each curve

is multiplied with a suitably chosen factor. All curves share the same shape as

proven by the nearly perfect overlap. Note that the degradation lost during the

short stress interruptions is restored within less than one decade and thus does

not affect the extracted exponent  of the time power-law.

of the time power-law.In the context of the universal behavior, special attention has been paid to the recovery phase. This was motivated by the notion that NBTI underlies reversible reaction kinetics. The degradation during the stress phase was assumed to be caused by the combination of a forward and a reverse rate. Therefore, the kinetics during stress were supposed to cover the whole physics, however, the individual contributions of the forward and the reverse rate are obscured. By contrast, only the reverse rate is activated during the relaxation phase, which is thus more suited for analyzing NBTI. In the following, some observations on the relaxation phase are summarized:

.

.

.

.These observations suggest the following procedure to process the recorded NBTI recovery data: First, the relaxation curves must be normalized to their last respective stress points, which are generally unknown but can be obtained using the back-extrapolation method proposed in [31]. Second, the relaxation times have to be scaled to their last accumulated stress time. The resulting curve can be best analytically described by the empirical relation [31] (cf. Fig. 1.4)

with ,

,  , and

, and  . In a further step, the universal

relaxation is extended by the so-called permanent component [58, 28, 26] attributed

to a mechanism with another physical origin. This permanent component, however, is

ascertained to be a slowly recovering component rather than a constant contribution

and is best represented by a power-law [59]. Separating the permanent from the

recoverable component

. In a further step, the universal

relaxation is extended by the so-called permanent component [58, 28, 26] attributed

to a mechanism with another physical origin. This permanent component, however, is

ascertained to be a slowly recovering component rather than a constant contribution

and is best represented by a power-law [59]. Separating the permanent from the

recoverable component  , the degradation during stress can be written as

with

, the degradation during stress can be written as

with  being the first stress measurement point. Alternatively, it can also be

formulated as

being the first stress measurement point. Alternatively, it can also be

formulated as  is the prefactor of a power law with exponent

is the prefactor of a power law with exponent  , where the subscripts

, where the subscripts  and

and  refer to the recoverable or the permanent component, respectively. Note that

refer to the recoverable or the permanent component, respectively. Note that

is larger than

is larger than  in equation (1.9) indicating that the permanent component

becomes dominant at large stress times [59]. The impact of the permanent

component is demonstrated in Fig. 1.5, where the long term recovery tails deviate

from the universal curve. However, universality is regained by accounting

for the permanent component. For times longer than

in equation (1.9) indicating that the permanent component

becomes dominant at large stress times [59]. The impact of the permanent

component is demonstrated in Fig. 1.5, where the long term recovery tails deviate

from the universal curve. However, universality is regained by accounting

for the permanent component. For times longer than  , the relaxation

data can be well approximated by a logarithmic behavior [60, 61] using the

expression

with

, the relaxation

data can be well approximated by a logarithmic behavior [60, 61] using the

expression

with  being a parameter. The first term at the right hand side of equation (1.10)

represents the recovering component, which shows a nearly logarithmic behavior, and

compares well with the short term part of expression (1.7) [60, 31]. In [61] the

prefactors

being a parameter. The first term at the right hand side of equation (1.10)

represents the recovering component, which shows a nearly logarithmic behavior, and

compares well with the short term part of expression (1.7) [60, 31]. In [61] the

prefactors  and

and  have been extracted from the eMSM data in

Fig. 1.3 for the time range

have been extracted from the eMSM data in

Fig. 1.3 for the time range  during stress and

during stress and  during

relaxation. A comparison of the prefactors has revealed a certain ratio

during

relaxation. A comparison of the prefactors has revealed a certain ratio  ,

meaning that the stress and relaxation curves have different slopes. This

asymmetry has long remained unrecognized but rules out several proposed NBTI

models.

,

meaning that the stress and relaxation curves have different slopes. This

asymmetry has long remained unrecognized but rules out several proposed NBTI

models.

clearly indicate the existence of a permanent component.

Bottom Right: The same as in the top panel but scaled to the last stress

value and normalized to the stress time. One can clearly recognize the deviation

from the universal behavior

clearly indicate the existence of a permanent component.

Bottom Right: The same as in the top panel but scaled to the last stress

value and normalized to the stress time. One can clearly recognize the deviation

from the universal behavior  . Bottom Left: Only a combination of a

recoverable and a permanent component can reproduce the expected universal

behavior.

. Bottom Left: Only a combination of a

recoverable and a permanent component can reproduce the expected universal

behavior.The logarithmic and power-law-like part of the stress curve along with the two components during recovery raise the question whether NBTI is governed by two mechanisms with one of them dominating in each of the time regimes. If this is the case, each of these mechanisms is highly likely to be subject to different field and temperature acceleration. Then the transition between these regimes should be controllable by varying the temperature and the electric field. However, no such transition has been observed so far. In [63], it has been argued that NBTI must be caused by either a single process or two tightly coupled ones. In the latter case, the interplay of both process enforces a single field dependence and temperature dependence without any transitions.