5.6 Extrapolation of Oxide Trap Contribution

As demonstrated above, during an OFIT measurement a distortion of  due

to oxide charges and due to the creation of defects during the low-level is

monitored. In order to analyze this distortion,

due

to oxide charges and due to the creation of defects during the low-level is

monitored. In order to analyze this distortion,  is determined to be the

lowest value of

is determined to be the

lowest value of  at which no hysteresis is observed. The dataset

at which no hysteresis is observed. The dataset

is then used to extrapolate the impact of oxide charges

is then used to extrapolate the impact of oxide charges  down to the stress-level. It is not possible to obtain this information

from the stress pulse because of the contribution of both parts

down to the stress-level. It is not possible to obtain this information

from the stress pulse because of the contribution of both parts  and

and  . Quite remarkably, the data [78] can be fit by a quadratic

polynomial, consistent with our NBTI experiments where we also observe a

quadratic (

. Quite remarkably, the data [78] can be fit by a quadratic

polynomial, consistent with our NBTI experiments where we also observe a

quadratic ( ) dependence of the hole-trapping component [99, 18, 98].

The hole-trapping theory developed in [98] was applied to our data and

excellent agreement was obtained. The difference between the actual signal

(

) dependence of the hole-trapping component [99, 18, 98].

The hole-trapping theory developed in [98] was applied to our data and

excellent agreement was obtained. The difference between the actual signal

( ) and the extrapolated curve in Fig. 5.15 and Fig. 5.16 finally gives

) and the extrapolated curve in Fig. 5.15 and Fig. 5.16 finally gives

.

.

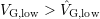

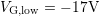

In Fig. 5.15 and Fig. 5.16 the extraction algorithm for  and

and  is

demonstrated. Stress and relaxation pulse responses both consist of two branches,

one falling and one rising, as marked by arrows. In the falling branch,

is

demonstrated. Stress and relaxation pulse responses both consist of two branches,

one falling and one rising, as marked by arrows. In the falling branch,  varies from

varies from  to

to  . In the rising branch,

. In the rising branch,  varies from

varies from  to

to

. Only pulses with constant

. Only pulses with constant  (or even without a hysteresis, i.e.

(or even without a hysteresis, i.e.

) can be used to create an extrapolation guess for higher

) can be used to create an extrapolation guess for higher  .

This ‘safe window’ ranges from

.

This ‘safe window’ ranges from  to

to  , where both branches are

indistinguishable.

, where both branches are

indistinguishable.

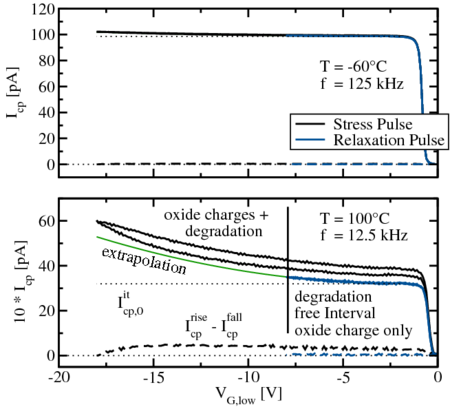

The extracted components for different temperatures and frequencies are

given in Fig. 5.17. The additionally created oxide traps  depend on

frequency as well as on temperature and clearly show

depend on

frequency as well as on temperature and clearly show  behavior.

The hysteresis due to additionally created traps

behavior.

The hysteresis due to additionally created traps  is independent of

frequency, but strongly dependent on temperature.

is independent of

frequency, but strongly dependent on temperature.

due

to oxide charges and due to the creation of defects during the low-level is

monitored. In order to analyze this distortion,

due

to oxide charges and due to the creation of defects during the low-level is

monitored. In order to analyze this distortion,  is determined to be the

lowest value of

is determined to be the

lowest value of  at which no hysteresis is observed. The dataset

at which no hysteresis is observed. The dataset

is then used to extrapolate the impact of oxide charges

is then used to extrapolate the impact of oxide charges  down to the stress-level. It is not possible to obtain this information

from the stress pulse because of the contribution of both parts

down to the stress-level. It is not possible to obtain this information

from the stress pulse because of the contribution of both parts  and

and  . Quite remarkably, the data [78] can be fit by a quadratic

polynomial, consistent with our NBTI experiments where we also observe a

quadratic (

. Quite remarkably, the data [78] can be fit by a quadratic

polynomial, consistent with our NBTI experiments where we also observe a

quadratic ( ) dependence of the hole-trapping component [99, 18, 98].

The hole-trapping theory developed in [98] was applied to our data and

excellent agreement was obtained. The difference between the actual signal

(

) dependence of the hole-trapping component [99, 18, 98].

The hole-trapping theory developed in [98] was applied to our data and

excellent agreement was obtained. The difference between the actual signal

( ) and the extrapolated curve in Fig. 5.15 and Fig. 5.16 finally gives

) and the extrapolated curve in Fig. 5.15 and Fig. 5.16 finally gives

.

.

for the stress pulse (

for the stress pulse ( =

=  ) and the relaxation pulse (

) and the relaxation pulse ( =

=  ), shown in

Fig.

), shown in

Fig.  . In the range

. In the range

, this difference is constant, implying no additional

creation of interface states. From this ‘safe window’ we extrapolate to

the minimum low-level to estimate the contribution due to oxide charges.

Note that the first branches

, this difference is constant, implying no additional

creation of interface states. From this ‘safe window’ we extrapolate to

the minimum low-level to estimate the contribution due to oxide charges.

Note that the first branches  of the stress and relaxation pulse differ

from each other due to pre-stress pulses between

of the stress and relaxation pulse differ

from each other due to pre-stress pulses between  and

and

. In fact, when using fresh devices for each measurement all

. In fact, when using fresh devices for each measurement all

would coincide.

would coincide.  and

and  is

demonstrated. Stress and relaxation pulse responses both consist of two branches,

one falling and one rising, as marked by arrows. In the falling branch,

is

demonstrated. Stress and relaxation pulse responses both consist of two branches,

one falling and one rising, as marked by arrows. In the falling branch,  varies from

varies from  to

to  . In the rising branch,

. In the rising branch,  varies from

varies from  to

to

. Only pulses with constant

. Only pulses with constant  (or even without a hysteresis, i.e.

(or even without a hysteresis, i.e.

) can be used to create an extrapolation guess for higher

) can be used to create an extrapolation guess for higher  .

This ‘safe window’ ranges from

.

This ‘safe window’ ranges from  to

to  , where both branches are

indistinguishable.

, where both branches are

indistinguishable.

.

.  depend on

frequency as well as on temperature and clearly show

depend on

frequency as well as on temperature and clearly show  behavior.

The hysteresis due to additionally created traps

behavior.

The hysteresis due to additionally created traps  is independent of

frequency, but strongly dependent on temperature.

is independent of

frequency, but strongly dependent on temperature.

follows

follows  , and depends on the frequency as well as on the temperature.

The hystereses displayed in the previous figures are due to additionally

created traps,

, and depends on the frequency as well as on the temperature.

The hystereses displayed in the previous figures are due to additionally

created traps,  , which are independent of the frequency but strongly

dependent on the temperature.

, which are independent of the frequency but strongly

dependent on the temperature.