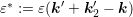

, the modulus

, the modulus  of the wave vector as a function of energy, the generalized density of

states

of the wave vector as a function of energy, the generalized density of

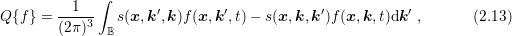

states  , and the scattering operator

, and the scattering operator  . However, the velocity term

. However, the velocity term  and the

density of states

and the

density of states  are not independent and depend on the dispersion relation

are not independent and depend on the dispersion relation  by

by

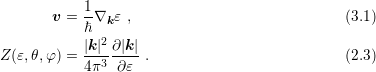

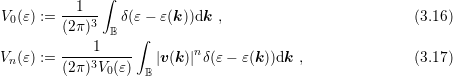

The SHE equations (2.34) and (2.35) incorporate material-specific properties by the velocity term

, the modulus

, the modulus  of the wave vector as a function of energy, the generalized density of

states

of the wave vector as a function of energy, the generalized density of

states  , and the scattering operator

, and the scattering operator  . However, the velocity term

. However, the velocity term  and the

density of states

and the

density of states  are not independent and depend on the dispersion relation

are not independent and depend on the dispersion relation  by

by

The second half of this chapter is devoted to the various scattering effects. Since scattering balances the energy gain of carriers due to the electric field, accurate expressions for the scattering operators are mandatory. Scattering mechanisms leading to a linear operator are discussed in Sec. 3.3, while the case of nonlinear scattering operators is investigated in Sec. 3.4.

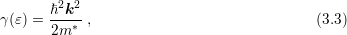

Due to the nonuniformity of the crystal lattice in silicon with respect to a change in direction, the dispersion relation linking the particle momentum with the particle energy cannot be accurately described by the idealized setting of an infinitely deep quantum well, for which the solution of Schrödinger’s equation yields a parabolic dependence of the energy on the wave vector:

is the scaled Planck constant and

is the scaled Planck constant and  is the effective mass. Still, this quadratic

relationship termed parabolic band approximation is a good approximation near the minimum of

the energy valley. Due to its simple analytical form, the parabolic dispersion relation is often

used up to high energies, for which it fails to provide an accurate description of the

material.

is the effective mass. Still, this quadratic

relationship termed parabolic band approximation is a good approximation near the minimum of

the energy valley. Due to its simple analytical form, the parabolic dispersion relation is often

used up to high energies, for which it fails to provide an accurate description of the

material.

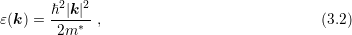

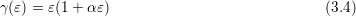

A more accurate approximation to the band structure in silicon can be obtained by a slight modification of the form

is called nonparabolicity factor; in the case

is called nonparabolicity factor; in the case

one obtains again (3.2). More complicated analytical dependencies of the energy on the

wave vector are certainly possible, but (3.4) already provides very good results in the

low-energy regime. The choice

one obtains again (3.2). More complicated analytical dependencies of the energy on the

wave vector are certainly possible, but (3.4) already provides very good results in the

low-energy regime. The choice  provides a good approximation of the dispersion

relation for electrons in relaxed silicon. However, for kinetic energies above

provides a good approximation of the dispersion

relation for electrons in relaxed silicon. However, for kinetic energies above  eV the

nonparabolic approximation fails to describe the nonmonotonicity of the density of states in

silicon.

eV the

nonparabolic approximation fails to describe the nonmonotonicity of the density of states in

silicon.

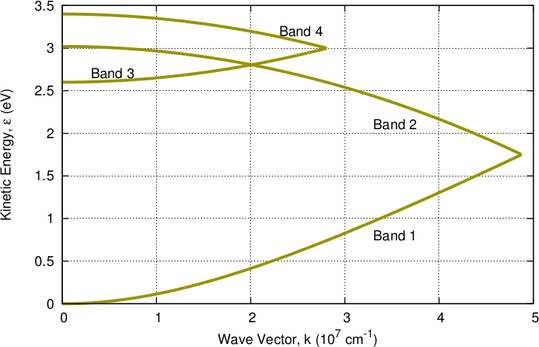

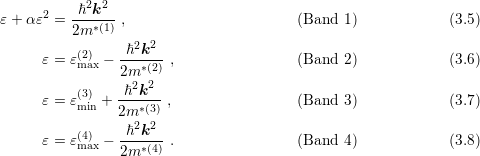

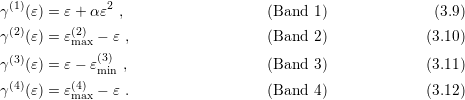

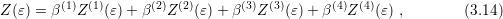

The deficiencies of the nonparabolic dispersion relation can be mitigated by a combination of four energy bands as proposed by Brunetti et. al. [11]:

,

,  and

and  respectively. The specific form of each

band is given by

respectively. The specific form of each

band is given by

is computed from the individual

densities of states by a weighted sum:

is computed from the individual

densities of states by a weighted sum:

,

,  account for the number of equivalent

symmetrical bands of the

account for the number of equivalent

symmetrical bands of the  -th band can be found together with the other parameters of the

multi-band model in Tab. 3.1.

-th band can be found together with the other parameters of the

multi-band model in Tab. 3.1.

| Band |  |  |  |  |  |

| 1 | 0.320 | 0 | 1.75 | 6 | 0.35 |

| 2 | 0.712 | 1.75 | 3.02 | 6 | 0 |

| 3 | 0.750 | 2.60 | 3.00 | 12 | 0 |

| 4 | 0.750 | 3.00 | 3.40 | 12 | 0 |

denotes the electron mass,

denotes the electron mass,  the multiplicity of the respective band and

the multiplicity of the respective band and  is the

nonparabolicity factor. Each band extends from

is the

nonparabolicity factor. Each band extends from  to

to  .

. The BTE has in principle to be solved in each energy band with index  for a distribution

function

for a distribution

function  . However, since the individual distribution functions for each energy band are not

of particular interest, it is preferred to have a single dispersion relation describing the total

distribution function

. However, since the individual distribution functions for each energy band are not

of particular interest, it is preferred to have a single dispersion relation describing the total

distribution function  .

.

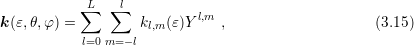

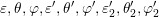

In order to account for the angular dependence of the energy on the wave vector in a semiconductor, the inverse dispersion relation is expanded as

and nonnegative

and nonnegative  -values,

which are a multiple of four, lead to nonzero expansion coefficients. The expansion coefficients

-values,

which are a multiple of four, lead to nonzero expansion coefficients. The expansion coefficients

can either be determined by an integration over spheres in

can either be determined by an integration over spheres in  -space, cf. (2.2), or by

minimization of certain target functionals such as the quadratic error of the scaled

moments

-space, cf. (2.2), or by

minimization of certain target functionals such as the quadratic error of the scaled

moments

denotes the Brillouin zone.

denotes the Brillouin zone.

A SHE of the valence band has been carried out by Kosina et al. [60] up to  eV.

Pham et al. [73] proposed a refined method for an expansion also including higher

energies. A fitted band structure based on SHE for the conduction band has been

presented by Matz et al. [69]. Due to the bijective mapping between energy and wave

vector, the velocity and the density of states are not in perfect agreement with full-band

data. Nevertheless, good results compared to the Monte Carlo method are obtained

[45].

eV.

Pham et al. [73] proposed a refined method for an expansion also including higher

energies. A fitted band structure based on SHE for the conduction band has been

presented by Matz et al. [69]. Due to the bijective mapping between energy and wave

vector, the velocity and the density of states are not in perfect agreement with full-band

data. Nevertheless, good results compared to the Monte Carlo method are obtained

[45].

is labelled Modena model, as it is

also used in e.g. [42].

is labelled Modena model, as it is

also used in e.g. [42].

A comparison of the presented energy band models is given in Fig. 3.2. Slight deviations of

the many-band model and the full-band density of states are due to different Monte Carlo data

used in [11]. While the many-band model provides a good fit for the density of states, it fails to

approximate the carrier velocity and is worse than the nonparabolic model (3.3). As expected, the

fitted band model provides the best accuracy, even though approximations are less accurate at

energies above  eV.

eV.

Vecchi et al. [107] used full-band Monte Carlo data for the velocity  and the generalized

density of states

and the generalized

density of states  for a first-order SHE. This is possible because in this case all terms with an

explicit representation of the band structure, i.e.

for a first-order SHE. This is possible because in this case all terms with an

explicit representation of the band structure, i.e.  , vanish. However, higher-order SHE does

not allow for a similar procedure, because the angular coupling term (2.33) does not

vanish any longer and an explicit expression for the modulus of the wave vector is

required.

, vanish. However, higher-order SHE does

not allow for a similar procedure, because the angular coupling term (2.33) does not

vanish any longer and an explicit expression for the modulus of the wave vector is

required.

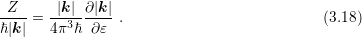

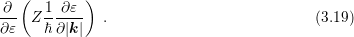

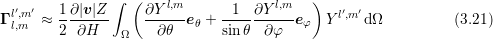

Recently, Jin et al. [48] suggested a reformulation as follows: Consider

, the expression can be further rearranged

to

, the expression can be further rearranged

to

While the band structure links the particle energy with the particle momentum, it does not fully describe the propagation of carriers. In the presence of an electrostatic force, carriers would be accelerated and thus gain energy indefinitely unless scattering with the crystal lattice or with other carriers is included in the model. The most important scattering mechanisms are discussed in the following. The scattering operator is assumed to be given in the form

,

need to be taken into account when comparing scattering rates from different sources. Note that

the numerator of the prefactor differs from the numerator used for the spherical projection (2.6)

due to the assumption that scattering does not change spin. Moreover, it should be noted again

that the commonly written small sample volume

,

need to be taken into account when comparing scattering rates from different sources. Note that

the numerator of the prefactor differs from the numerator used for the spherical projection (2.6)

due to the assumption that scattering does not change spin. Moreover, it should be noted again

that the commonly written small sample volume  as prefactor for the scattering integral is not

written explicitly in the following.

as prefactor for the scattering integral is not

written explicitly in the following.

Atoms in the crystal lattice vibrate around their fixed equilibrium locations at nonzero

temperature. These vibrations are quantized by phonons with energy  . Acoustic

vibrations refer to a coherent movement of the lattice atoms out of their equilibrium positions.

Depending on the displacements with respect to the direction of propagation of the lattice wave,

transversal (TA) and longitudinal (LA) acoustic modes are distinguished.

. Acoustic

vibrations refer to a coherent movement of the lattice atoms out of their equilibrium positions.

Depending on the displacements with respect to the direction of propagation of the lattice wave,

transversal (TA) and longitudinal (LA) acoustic modes are distinguished.

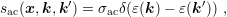

Since the change in particle energy due to acoustic phonon scattering is very small, the process is typically modelled as an elastic process [47], which does not couple different energy levels. The scattering rate can thus be written as

| (3.22) |

where the coefficient  is given by

is given by

is the deformation potential,

is the deformation potential,  is the density of mass, and

is the density of mass, and  is the longitudinal

sound velocity, cf. Tab. 3.2.

is the longitudinal

sound velocity, cf. Tab. 3.2.

| Si | Ge | |

|  g/cm g/cm | 5.32 g/cm |

|  cm/s cm/s |  cm/s cm/s |

|  |  |

|  eV eV |  eV eV |

|  eV eV |  eV eV |

and

and  are used to distinguish between electrons and holes.

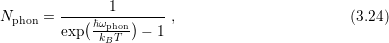

are used to distinguish between electrons and holes.Optical phonon scattering refers to an out-of-phase movement of lattice atoms. In ionic crystals, these vibrations can be excited by infrared radition, which explains the name. Similar to acoustic phonon scattering, transversal (TO) and longitudinal (LO) modes are distinguised.

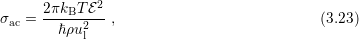

Since the involved phonon energies are rather high, cf. Tab. 3.3, optical phonon scattering is

typically modeled as an inelastic process leading to a change of the particle energy. With the

phonon occupation number  given by the Bose-Einstein statistics

given by the Bose-Einstein statistics

and the final state

and the final state  can be written as

can be written as

![[

sop(x,k,k′) = σopNphon δ(ε(k) − ε(k′) + ℏωop)

+ (1+ N )δ(ε(k) − ε(k′) − ℏω )] ,

phon op](diss-et545x.png) | (3.25) |

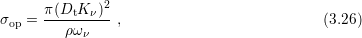

where  is symmetric in

is symmetric in  and

and  and given by

and given by

, mass density

, mass density  , and phonon frequency

, and phonon frequency  . Values for the

individual modes can be found in Tab. 3.3. It should be noted that optical phonon

scattering couples the energy levels

. Values for the

individual modes can be found in Tab. 3.3. It should be noted that optical phonon

scattering couples the energy levels  ,

,  and

and  in an asymmetric

manner, because scattering from higher energy to lower energy is more likely than vice

versa.

in an asymmetric

manner, because scattering from higher energy to lower energy is more likely than vice

versa.

| Si | Ge | ||||

| Mode |  |  |  |  |

| TA |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |

| LA |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |

| LO |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |

| TA |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |

| LA |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |

| TO |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |  eV/cm eV/cm |  meV meV |

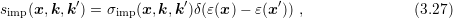

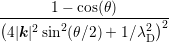

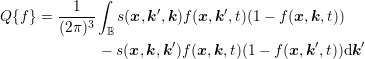

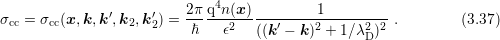

Dopants in a semiconductor are fixed charges inside the crystal lattice. Since carriers are charged particles as well, their trajectories are influenced by these fixed charges, leading to a change of their momentum. The model by Brooks and Herring [10, 47] suggests an elastic scattering process with scattering coefficient

is symmetric in

is symmetric in  and

and  and given by

and given by

and

and  denote the acceptor

and donator concentrations respectively. The Debye length

denote the acceptor

and donator concentrations respectively. The Debye length  under assumption of local

equilibrium is given by

under assumption of local

equilibrium is given by

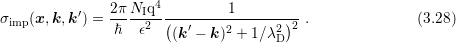

. This complication can be circumvented by approximating the anisotropic

coefficient (3.27) by an elastic-isotropic process with the same momentum relaxation time

. This complication can be circumvented by approximating the anisotropic

coefficient (3.27) by an elastic-isotropic process with the same momentum relaxation time  [52]. The momentum relaxation time is computed for an isotropic dispersion relation by an

integration over the whole Brillouin zone and by weighting the change of direction of the

momentum [67]:

[52]. The momentum relaxation time is computed for an isotropic dispersion relation by an

integration over the whole Brillouin zone and by weighting the change of direction of the

momentum [67]:

= =  ∫

Bsimp(x,k,k′)(1 − cos(θ))dk3 ∫

Bsimp(x,k,k′)(1 − cos(θ))dk3 |

-axis for the integration in the Brillouin zone is chosen such that it is aligned with

-axis for the integration in the Brillouin zone is chosen such that it is aligned with

, hence the angle between

, hence the angle between  and

and  is given by the inclination

is given by the inclination  . Transformation to

spherical coordinates leads to

. Transformation to

spherical coordinates leads to

= =  ∫

0∞∫

0π ∫

0∞∫

0π sinθdθZdε sinθdθZdε |

is independent of the angles because of the assumption of an

isotropic dispersion relation. The integral over the inclination

is independent of the angles because of the assumption of an

isotropic dispersion relation. The integral over the inclination  can be computed analytically

as

can be computed analytically

as

∫

0π sinθdθ = sinθdθ =  ![[ 2 2 ]

ln(1 + 4λ2D|k|2)− --4λD-|k2|---

1 + 4λD|k|2](diss-et616x.png) . . |

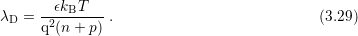

![4 [ 2 2 ]

σimp;iso(x,k,k ′) = π-NIq---1--- ln(1 + 4λ2|k|2)− --4λD-|k-|-- (3.30)

ℏ ϵ2 4|k |4 D 1 + 4λ2D |k|2](diss-et617x.png)

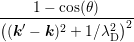

should

be evaluated consistently with the approximated band, therefore the transformation (3.20) needs

to be employed for the full-band case. Moreover, since the Brooks-Herring model fails to correctly

describe the carrier mobility at high doping concentrations, an empirical fit factor depicted in

Fig. 3.3 is usually employed additionally [52] in order to reproduce the Caughey-Thomas

expression for the mobility [15].

should

be evaluated consistently with the approximated band, therefore the transformation (3.20) needs

to be employed for the full-band case. Moreover, since the Brooks-Herring model fails to correctly

describe the carrier mobility at high doping concentrations, an empirical fit factor depicted in

Fig. 3.3 is usually employed additionally [52] in order to reproduce the Caughey-Thomas

expression for the mobility [15].

The scattering operator in low-density approximation for single carrier processes is linear, which is very attractive from a computational point of view. Consequently, scattering processes leading to a nonlinear scattering operator are often neglected in order to avoid nonlinear iteration schemes. In the following, two such types of scattering mechanisms are considered.

A high population of the conduction band can lead to the case that the distribution function

takes large values near the band edge, thus the term  cannot be approximated with

cannot be approximated with  any longer:

any longer:

| (3.31) |

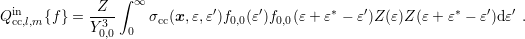

Repeating the steps from Sec. 2.2, one finally obtains for the projected in-scattering operator assuming velocity randomization and a scattering rate independent of the angles

![[ ][f] (x,ε± ℏω ,t)

Qiηn,l,m{f } = σ η(x, ε± ℏω η,ε) Zl,m(ε)− [f]l,m---0,0---------η---. (3.32)

Y0,0](diss-et623x.png)

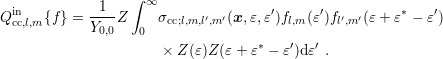

![[ ]

Qout {f } = σ (x,ε,ε± ℏω )Z (ε± ℏω )− [f] (x, ε± ℏω ,t) [f]l,m . (3.33)

η,l,m η η 0,0 η 0,0 η Y0,0](diss-et624x.png)

Numerical results in [43] confirm that the low-density approximation does not have a high impact on macroscopic quantities such as the electron density or carrier velocities, but notable differences in the distribution function are obtained near the band edge. The carrier population is then shifted towards higher energies, because all states at lower energies are already populated.

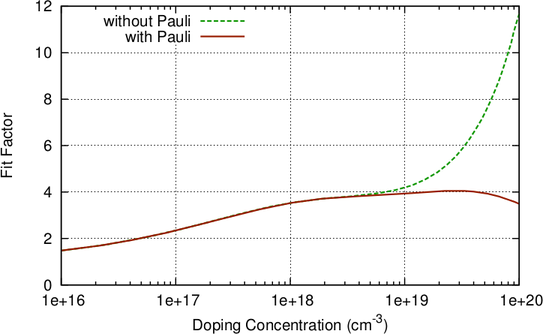

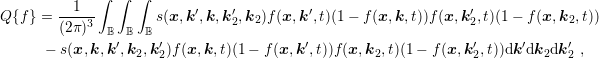

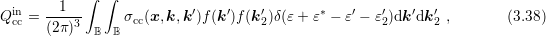

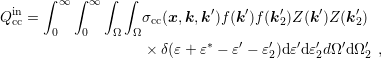

The linear scattering operators in Sec. 3.3 stem from the scattering of carriers with noncarriers. Very important for particularly the high energy tail of the distribution function is carrier-carrier scattering [79]. A carrier-carrier scattering mechanism requires that the two source states are occupied, and the two final states after scattering are empty. This leads to a scattering operator of the form

| (3.34) |

where the scattering coefficient  now depends on the spatial location and on two pairs

of initial and final states. With a low-density approximation, the nonlinearity of degree four of the

carrier-carrier scattering operator reduces to second order:

now depends on the spatial location and on two pairs

of initial and final states. With a low-density approximation, the nonlinearity of degree four of the

carrier-carrier scattering operator reduces to second order:

| (3.35) |

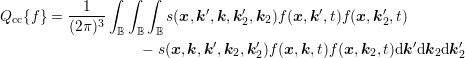

The scattering coefficient can be derived to be of the form [96, 99]

replaced by the carrier density

replaced by the carrier density  . Since

. Since  only depends via

only depends via  on the difference of

the initial and the final state of one of the two carriers, the shorthand notation

on the difference of

the initial and the final state of one of the two carriers, the shorthand notation  is

used in the following.

is

used in the following.

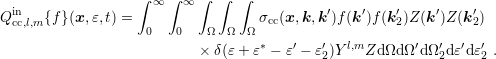

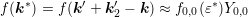

Carrier-carrier scattering, particularly electron-electron scattering, has so far been discussed for first-order SHE only [108, 110]. In a joint work with Peter Willibald Lagger [62], the author has recently extended the method to arbitrary-order SHE, and the derivation is given in the following.

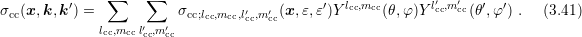

The scattering operator (3.35) is again split into an in-scattering term  and an

out-scattering term

and an

out-scattering term  as in Sec. 2.2. Inserting (3.36) into (3.35), one integration can be

carried out due to the momentum conservation. An integration with respect to

as in Sec. 2.2. Inserting (3.36) into (3.35), one integration can be

carried out due to the momentum conservation. An integration with respect to  yields

yields

of the second particle involved in the

scattering process. A transformation of the two integrals to spherical coordinates leads

to

of the second particle involved in the

scattering process. A transformation of the two integrals to spherical coordinates leads

to

| (3.39) |

where  and similarly for

and similarly for  and

and  . A projection onto the spherical harmonic

. A projection onto the spherical harmonic

yields

yields

| (3.40) |

Up to now, no approximations have been applied. However, a direct evaluation of these nested integrals at each node in the simulation domain is certainly prohibitive for the use within a simulator due to excessive execution times. Consequently, the further derivation is based on the following two assumptions:

can be taken as an external parameter. In principle, the energy

can be taken as an external parameter. In principle, the energy

of the second particle before scattering depends due to energy conservation on

all variables, i.e.

of the second particle before scattering depends due to energy conservation on

all variables, i.e.  . Because the asymptotically exponential

distribution of carriers with respect to energy, it is plausible, yet heuristic, that the

second particle has an energy close to the band gap. Since no additional information

about the second particle involved is known, the average energy is taken for

. Because the asymptotically exponential

distribution of carriers with respect to energy, it is plausible, yet heuristic, that the

second particle has an energy close to the band gap. Since no additional information

about the second particle involved is known, the average energy is taken for  ,

which is accessible due to the nonlinear iteration scheme required for the solution of

the discrete set of equations.

,

which is accessible due to the nonlinear iteration scheme required for the solution of

the discrete set of equations.

can be expanded into spherical harmonics with

respect to

can be expanded into spherical harmonics with

respect to  and

and  . This can for example be achieved by using the isotropic

approximation (3.30) in order to obtain an isotropic scattering rate with equal

macroscopic relaxation time. As an alternative, one may directly compute a spherical

projection in order to obtain the expansion coefficients

. This can for example be achieved by using the isotropic

approximation (3.30) in order to obtain an isotropic scattering rate with equal

macroscopic relaxation time. As an alternative, one may directly compute a spherical

projection in order to obtain the expansion coefficients  of the

expansion

of the

expansion

in the following. The same derivations

can also be carried out for the coefficients

in the following. The same derivations

can also be carried out for the coefficients  , but only the final result for this more

general case is given at the end of the derivation.

, but only the final result for this more

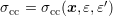

general case is given at the end of the derivation.With these assumptions, one can split the integrands to

| (3.42) |

An expansion of  into spherical harmonics, the use of the delta distribution for an

elimination of the integral over

into spherical harmonics, the use of the delta distribution for an

elimination of the integral over  , and the assumption of spherical energy bands leads

to

, and the assumption of spherical energy bands leads

to

| (3.43) |

Summing up, the projected in-scattering operator is given by

| (3.44) |

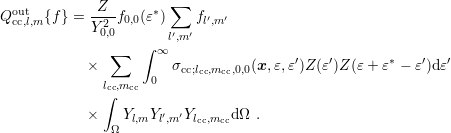

For the more general case of an expansion of the scattering coefficient (3.41), one obtains again with the assumption of spherical energy bands

| (3.45) |

The projection of the out-scattering operator starts with the same steps as for the in-scattering operator in order to arrive at

| (3.46) |

The angles  and

and  depend in a complicated way on the other angles, therefore rather crude

simplifications are applied. Scattering with another carrier is to a first approximation determined

by the density of carriers at the particular location inside the device. Consequently, the

distribution function of the second particle, which is described by

depend in a complicated way on the other angles, therefore rather crude

simplifications are applied. Scattering with another carrier is to a first approximation determined

by the density of carriers at the particular location inside the device. Consequently, the

distribution function of the second particle, which is described by  and

and  , is

approximated by the isotropic part of the distribution function only, since it fully describes the

carrier density. With

, is

approximated by the isotropic part of the distribution function only, since it fully describes the

carrier density. With  and considering

and considering  again as the

average energy, (3.46) simplifies to

again as the

average energy, (3.46) simplifies to

| (3.47) |

The more general case of an expansion of the scattering coefficient (3.41) results in

| (3.48) |

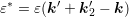

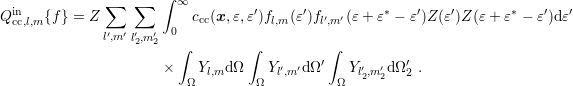

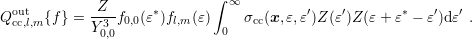

For the full projected scattering operator, one thus obtains

![Z ∫ ∞ [

Qcc,l,m {f} = --3- σcc(x,ε,ε′)f0,0(ε′)f0,0(ε+ ε∗ − ε′)

Y0,0 0 ]

− f0,0(ε∗)fl,m (ε)Z (ε)Z(ε+ ε∗ − ε′)dε′ .](diss-et672x.png) | (3.49) |

With the use of an expansion of the scattering coefficient (3.41), one obtains

![∑ ∑ ∫ ∞

Qcc,l,m {f} = -Z-- σcc;l ,m ,l′,m′ (x, ε,ε′)

Y02,0l ,m l′,m′ 0 cc cc cc cc

cc cccc cc [

Y0,0flcc,mcc(ε′)fl′cc,m′cc(ε + ε∗ − ε′)

∑ ∫ ]

− f0,0(ε∗) fl′,m′ Yl,mYl′,m ′Ylcc,mccdΩ

l′,m′ Ω

∗ ′ ′

× Z (ε)Z(ε+ ε − ε)dε .](diss-et673x.png) | (3.50) |

One can immediately see that the full scatter operator vanishes for the equilibrium case, where

is given by a Maxwell distribution. Therefore, even though simplifications have been used for

the separate derivation of the projected equations for the in- and the out-scattering operators, the

resulting expressions are consistent.

is given by a Maxwell distribution. Therefore, even though simplifications have been used for

the separate derivation of the projected equations for the in- and the out-scattering operators, the

resulting expressions are consistent.