|  |  |

While mechanics in its classical form describes the world with determinism, even if predictability is undermined, when turning to statistical methods, this is drastically changed in a quantum mechanical setting. Already well established and tangible concepts such as particles are recast in the setting of quantum mechanics using wave functions. This makes effects describable, which are completely unavailable to the classical setting, without changing the Newtonian structure of the universe with its absolute time.

Quantum mechanics is often introduced in a detached manner with little to no connection to the classical settings supporting utterly alien effects which even border on the bizarre. It is therefore interesting to note that the governing structures so painstakingly uncovered by scientists over the course of time for the classical case are still present in the quantum setting. This comes as no surprise in light that the macroscopic world of every day life follows classical rules, wherefore the descriptions of quantum systems should always yield classical behaviour, when taken to the appropriate limit.

The setting of the quantum world is chosen to be a complex Hilbert space from which functions are chosen to represent the state of a system. The structure of this complex Hilbert space together with a link to the macroscopic world is sufficient to extract the governing equation of the system.

The wave functions  , which are drawn from the complex Hilbert space

, which are drawn from the complex Hilbert space  are acted upon mappings,

which are often called operators in this context, to describe transitions of states. While the

are acted upon mappings,

which are often called operators in this context, to describe transitions of states. While the  are

capable of encoding the state of a quantum system, they elude observations completely. At first this

seems to contradict the requirement that scientific theories must be falsifiable [93] and thus accessible

to some form of experiments and measurement. However, observables can be constructed from

are

capable of encoding the state of a quantum system, they elude observations completely. At first this

seems to contradict the requirement that scientific theories must be falsifiable [93] and thus accessible

to some form of experiments and measurement. However, observables can be constructed from  in a

systematic fashion, which are again accessible to measurements and thus to testing of the theory.

Without touching upon the, for many researchers sensitive, topic of the many different interpretations of

quantum mechanics [94][95][96][97] the wave functions

in a

systematic fashion, which are again accessible to measurements and thus to testing of the theory.

Without touching upon the, for many researchers sensitive, topic of the many different interpretations of

quantum mechanics [94][95][96][97] the wave functions  need to meet the following

property

need to meet the following

property

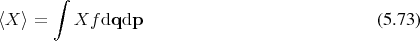

The prescription of constructing observables yields expectation values (Definition 101) of previously classically determined entities such as location or momentum. It is thus a reasonable demand that this mapping shall produce entities with their expected structures, e.g., appropriate tensors (Definition 54).

and classical observables is established

and classical observables is established

is the classical expectation value (Definition 101) and

is the classical expectation value (Definition 101) and  is a operator on elements of the

Hilbert space. This defines the observable operators on

is a operator on elements of the

Hilbert space. This defines the observable operators on  .

.

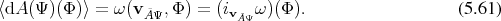

As in the classical case, a differential form (Definition 59) is derivable with a function  on the

Hilbert space

on the

Hilbert space  . At a point

. At a point  for a tangent vector

for a tangent vector  (Definition 48) using an arbitrary

parameter

(Definition 48) using an arbitrary

parameter  this gives

this gives

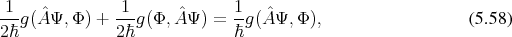

In case  is self adjoint with respect to the scalar product, this can be reshuffled to

is self adjoint with respect to the scalar product, this can be reshuffled to

is also a K¨ahler space (Definition 85), the Hermitian inner

product (Definition 77) of

is also a K¨ahler space (Definition 85), the Hermitian inner

product (Definition 77) of  may be rendered as a composition of a Riemannian component

may be rendered as a composition of a Riemannian component

(Definition 76) and a symplectic component

(Definition 76) and a symplectic component  (Definition 81).

(Definition 81).

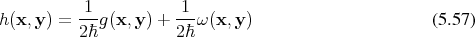

with an operator

with an operator  by

by

.

.

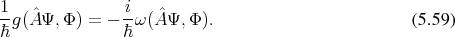

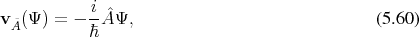

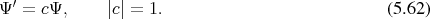

Thus the structures governing the evolution of the classical case, in the form of Hamiltonian vector fields, are also recognizable in a quantum system. While all of the Hilbert space is endowed with the symplectic structure, the normalization requirement confines the selection of states to the unit hyper-sphere. However, this restriction is not sufficient to remove all ambiguity, since it still remains in the form of uni-modular factors

. This projective space may now be regarded as a phase space connected to a physical

system.

. This projective space may now be regarded as a phase space connected to a physical

system.

In case of the Hamiltonian operator, the prescription 5.60 of assigning vector fields to operators yields exactly Schr¨odinger’s equation as can be seen by

which is the main governing equation of the quantum system. Thus the Hamiltonian vector field defined in this fashion is indeed responsible for the evolution of the quantum system in the Schr¨odinger picture of quantum mechanics, where operators remain constant and the states evolve.

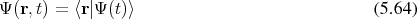

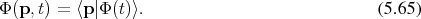

While a function  captures a state completely, descriptions usually employ a representation

using either position

captures a state completely, descriptions usually employ a representation

using either position  or momentum

or momentum  representations, which may be obtained by (utilizing Bra-Ket

notation introduced in Section 4.6.2)

representations, which may be obtained by (utilizing Bra-Ket

notation introduced in Section 4.6.2)

where  is the spatial dimension of the problem under investigation.

is the spatial dimension of the problem under investigation.

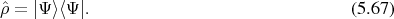

These descriptions account for half the degrees of freedom implicitly, while exposing only the other half. It is, however, possible to construct a representation, which explicitly recovers all degrees of freedom. The density operator and the density matrix are such representations. The density operator is given by

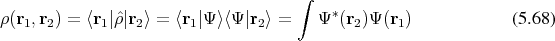

is obtained, which may be seen as a measure of correlation between two

positions

is obtained, which may be seen as a measure of correlation between two

positions  and

and  and retains all state information encoded in

and retains all state information encoded in  , as may be reinforced when

reformulating Equation (5.54) as

, as may be reinforced when

reformulating Equation (5.54) as

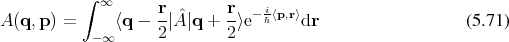

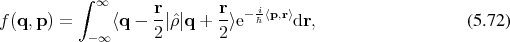

Utilizing such a representation, which provides information about the correlation of all of the points in

the problem domain, it is possible to also construct a representation which uses the position  and the

momentum

and the

momentum  , or wave vector

, or wave vector  associated by

associated by

is obtained,

is obtained,

.

.

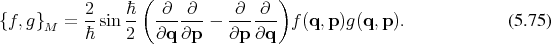

Since the transform linking the representations in terms of  and

and  is linear, the evolution of the

system may be expressed in either of them equivalently. The structures inherent to the space of quantum

mechanics also allow to formulate the evolution of a physical quantity, such as for the

is linear, the evolution of the

system may be expressed in either of them equivalently. The structures inherent to the space of quantum

mechanics also allow to formulate the evolution of a physical quantity, such as for the  as

as

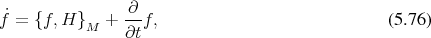

![[ ]

ˆρ˙= ρˆ, ˆH + ∂-ˆρ, (5 .74)

∂t](whole939x.png)

, thus this construct meets a basic property demanded from a quantum

description.

, thus this construct meets a basic property demanded from a quantum

description.

|  |  |