6.2 Standard Model of Kirton and Uren

Since the McWhorter model suffers from a weak temperature dependence of  and small time constants, Kirton and Uren [56] incorporated field-independent

barriers

and small time constants, Kirton and Uren [56] incorporated field-independent

barriers  in the cross sections

in the cross sections  and

and  (see Section 2.5). The ‘ad

hoc’ introduction of these barriers has been motivated by the theory of nonradiative

multi-phonon transitions (NMP) process [115]. However, Kirton and Uren have not

provided a detailed theoretical derivation based on this NMP theory. Nevertheless,

their work is regarded as a substantial improvement in the interpretation of charge

trapping at semiconductor-oxide interfaces and thus also referred to as the standard

model throughout this thesis. In an extended version of the McWhorter

model, the holes can also be captured by traps with an energy below the

substrate valence band. As illustrated in Fig. 2.5 of Section 2.5.2, the required

barriers consist of two components, namely

(see Section 2.5). The ‘ad

hoc’ introduction of these barriers has been motivated by the theory of nonradiative

multi-phonon transitions (NMP) process [115]. However, Kirton and Uren have not

provided a detailed theoretical derivation based on this NMP theory. Nevertheless,

their work is regarded as a substantial improvement in the interpretation of charge

trapping at semiconductor-oxide interfaces and thus also referred to as the standard

model throughout this thesis. In an extended version of the McWhorter

model, the holes can also be captured by traps with an energy below the

substrate valence band. As illustrated in Fig. 2.5 of Section 2.5.2, the required

barriers consist of two components, namely  and

and  . The latter is

the required minimum energy for a hole capture process while

. The latter is

the required minimum energy for a hole capture process while  is

the barrier component which must be overcome for hole capture as well

as emission. In this variant, the capture and emission time constants read

is

the barrier component which must be overcome for hole capture as well

as emission. In this variant, the capture and emission time constants read

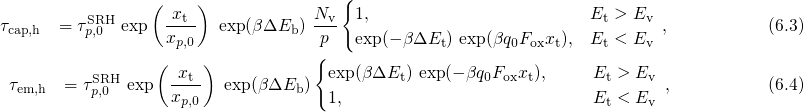

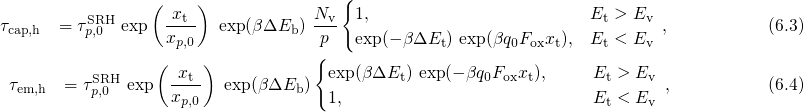

where the traps are not restricted to lie within the bandgap. Its behavior with

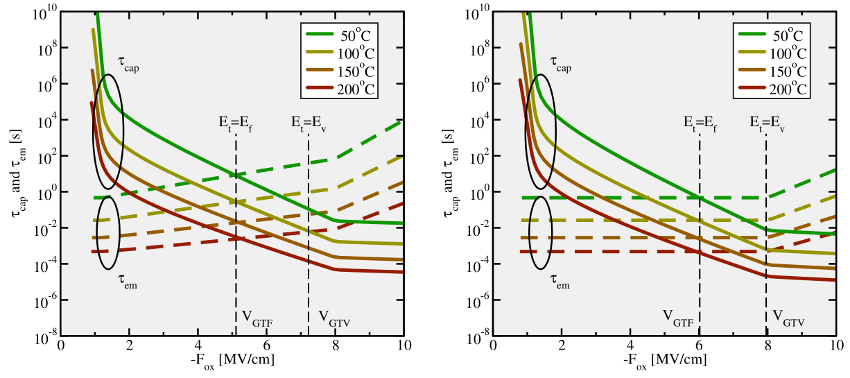

respect to the temperature and the oxide field is illustrated in Fig. 6.1 and evaluated

based on the TDDS checklist in Table 6.1. When the trap level lies below the valence

band edge ( ),

),  shows an exponential field dependence, which is

superimposed by a sharp peak due to a drop of the hole concentration at weak

oxide fields. Comparing the model to the experimental TDDS data (see

Section 1.3.4), this exponential behavior allows for reasonable and approximative fits

to

shows an exponential field dependence, which is

superimposed by a sharp peak due to a drop of the hole concentration at weak

oxide fields. Comparing the model to the experimental TDDS data (see

Section 1.3.4), this exponential behavior allows for reasonable and approximative fits

to  but it is incompatible with the observed curvature in

but it is incompatible with the observed curvature in  .

Furthermore, the model predicts

.

Furthermore, the model predicts  to be field insensitive for

to be field insensitive for  according to the equations (6.4). It should be mentioned at this point that the

derivation of the analytical expression (6.3) and (6.4) is based on Boltzmann

statistics, leading to small deviations in

according to the equations (6.4). It should be mentioned at this point that the

derivation of the analytical expression (6.3) and (6.4) is based on Boltzmann

statistics, leading to small deviations in  and

and  compared to the

simulations of Fig. 6.1 (left) using Fermi-Dirac statistics. The weak field

dependence of the simulated

compared to the

simulations of Fig. 6.1 (left) using Fermi-Dirac statistics. The weak field

dependence of the simulated  reasonably agrees with the behavior

of ‘normal’ (constant emission times) but is inconsistent with as well as

‘anomalous’ traps (a drop at weak oxide fields). Nevertheless, Fig. 6.1 reveals that

the introduction of

reasonably agrees with the behavior

of ‘normal’ (constant emission times) but is inconsistent with as well as

‘anomalous’ traps (a drop at weak oxide fields). Nevertheless, Fig. 6.1 reveals that

the introduction of  yields the required temperature activation and

larger time constants in agreement with the points (ii) and (v) of the TDDS

findings.

yields the required temperature activation and

larger time constants in agreement with the points (ii) and (v) of the TDDS

findings.

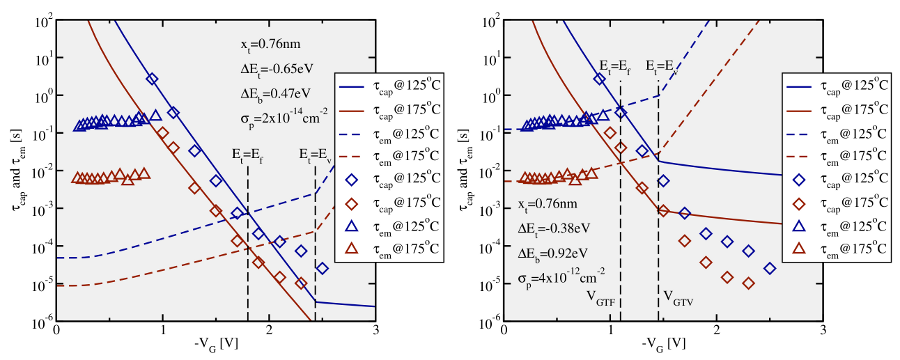

A fit of the Kirton model to the experimental TDDS data is presented in Fig. 6.2.

Although the model can reproduce some features seen in the TDDS data, except

for the curvature in  , no reasonable agreement with the measurement

data could be achieved. This discrepancy can be explained as follows: The

exponential bias dependence extends up to a voltage

, no reasonable agreement with the measurement

data could be achieved. This discrepancy can be explained as follows: The

exponential bias dependence extends up to a voltage  at which

at which  coincides with

coincides with  . In Fig. 6.2 (left)

. In Fig. 6.2 (left)  is approximately

is approximately  so

that

so

that  shows an exponential bias dependence up to this value and

becomes constant afterwards. Therefore,

shows an exponential bias dependence up to this value and

becomes constant afterwards. Therefore,  must be chosen such that

must be chosen such that  lies above the voltage range used in the measurements. This is only the

case for defects whose trap levels

lies above the voltage range used in the measurements. This is only the

case for defects whose trap levels  are situated sufficiently low. Note

that those defects are also characterized by a large

are situated sufficiently low. Note

that those defects are also characterized by a large  , which marks the

voltage where

, which marks the

voltage where  coincides with

coincides with  . After equation (2.66), their

. After equation (2.66), their  must equal their

must equal their  at

at  , visible as the crossings between

, visible as the crossings between  and

and  in Fig. 6.2. At a low gate bias, their trap levels are moved far

below

in Fig. 6.2. At a low gate bias, their trap levels are moved far

below  so that their emission times fall several orders of magnitude below

their corresponding capture time constants. The large difference between

so that their emission times fall several orders of magnitude below

their corresponding capture time constants. The large difference between

and

and  predicted by the Kirton model is inconsistent with the

experimental TDDS data. Additionally, a fit of the Kirton model to

predicted by the Kirton model is inconsistent with the

experimental TDDS data. Additionally, a fit of the Kirton model to  is

presented in Fig. 6.1 (right). It clearly shows that the simulated

is

presented in Fig. 6.1 (right). It clearly shows that the simulated  fails to

reproduce the experimentally obtained

fails to

reproduce the experimentally obtained  when a good match with

when a good match with  is

achieved.

is

achieved.

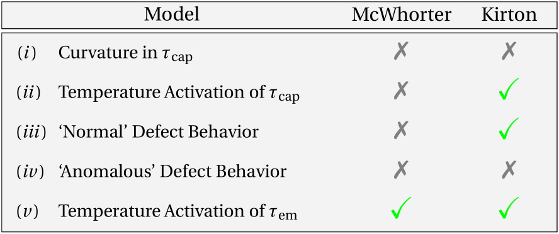

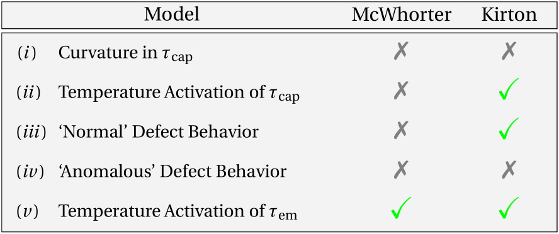

Table 6.1: Checklist for a TDDS defect. The individual criteria stem from the

TDDS data addressed in Section 1.3.4. The McWhorter as well as the Kirton

model do not fulfill all criteria and thus do not describe the defects seen in

TDDS experiments.

and small time constants, Kirton and Uren [56] incorporated field-independent

barriers

and small time constants, Kirton and Uren [56] incorporated field-independent

barriers  in the cross sections

in the cross sections  and

and  (see Section 2.5). The ‘ad

hoc’ introduction of these barriers has been motivated by the theory of nonradiative

multi-phonon transitions (NMP) process [115]. However, Kirton and Uren have not

provided a detailed theoretical derivation based on this NMP theory. Nevertheless,

their work is regarded as a substantial improvement in the interpretation of charge

trapping at semiconductor-oxide interfaces and thus also referred to as the standard

model throughout this thesis. In an extended version of the McWhorter

model, the holes can also be captured by traps with an energy below the

substrate valence band. As illustrated in Fig. 2.5 of Section 2.5.2, the required

barriers consist of two components, namely

(see Section 2.5). The ‘ad

hoc’ introduction of these barriers has been motivated by the theory of nonradiative

multi-phonon transitions (NMP) process [115]. However, Kirton and Uren have not

provided a detailed theoretical derivation based on this NMP theory. Nevertheless,

their work is regarded as a substantial improvement in the interpretation of charge

trapping at semiconductor-oxide interfaces and thus also referred to as the standard

model throughout this thesis. In an extended version of the McWhorter

model, the holes can also be captured by traps with an energy below the

substrate valence band. As illustrated in Fig. 2.5 of Section 2.5.2, the required

barriers consist of two components, namely  and

and  . The latter is

the required minimum energy for a hole capture process while

. The latter is

the required minimum energy for a hole capture process while  is

the barrier component which must be overcome for hole capture as well

as emission. In this variant, the capture and emission time constants read

is

the barrier component which must be overcome for hole capture as well

as emission. In this variant, the capture and emission time constants read

),

),  shows an exponential field dependence, which is

superimposed by a sharp peak due to a drop of the hole concentration at weak

oxide fields. Comparing the model to the experimental TDDS data (see

Section 1.3.4), this exponential behavior allows for reasonable and approximative fits

to

shows an exponential field dependence, which is

superimposed by a sharp peak due to a drop of the hole concentration at weak

oxide fields. Comparing the model to the experimental TDDS data (see

Section 1.3.4), this exponential behavior allows for reasonable and approximative fits

to  but it is incompatible with the observed curvature in

but it is incompatible with the observed curvature in  .

Furthermore, the model predicts

.

Furthermore, the model predicts  to be field insensitive for

to be field insensitive for  according to the equations (6.4). It should be mentioned at this point that the

derivation of the analytical expression (6.3) and (6.4) is based on Boltzmann

statistics, leading to small deviations in

according to the equations (6.4). It should be mentioned at this point that the

derivation of the analytical expression (6.3) and (6.4) is based on Boltzmann

statistics, leading to small deviations in  and

and  compared to the

simulations of Fig. 6.1 (left) using Fermi-Dirac statistics. The weak field

dependence of the simulated

compared to the

simulations of Fig. 6.1 (left) using Fermi-Dirac statistics. The weak field

dependence of the simulated  reasonably agrees with the behavior

of ‘normal’ (constant emission times) but is inconsistent with as well as

‘anomalous’ traps (a drop at weak oxide fields). Nevertheless, Fig. 6.1 reveals that

the introduction of

reasonably agrees with the behavior

of ‘normal’ (constant emission times) but is inconsistent with as well as

‘anomalous’ traps (a drop at weak oxide fields). Nevertheless, Fig. 6.1 reveals that

the introduction of  yields the required temperature activation and

larger time constants in agreement with the points (

yields the required temperature activation and

larger time constants in agreement with the points (

are plotted as solid lines, while the

are plotted as solid lines, while the  are

depicted by dashed lines. The vertical dashed lines mark the values of

are

depicted by dashed lines. The vertical dashed lines mark the values of  or

or

when the trap level

when the trap level  passes either the Fermi level or the valence band

edge in the substrate, respectively. Equation (

passes either the Fermi level or the valence band

edge in the substrate, respectively. Equation ( remains constant in the region

remains constant in the region  as

shown in the right figure. Using more accurate Fermi-Dirac statistics the

emission time constants are subject to a weak field dependence (cf. left figure).

On the logarithmic scale, the

as

shown in the right figure. Using more accurate Fermi-Dirac statistics the

emission time constants are subject to a weak field dependence (cf. left figure).

On the logarithmic scale, the  follow a linear behavior in

follow a linear behavior in  over a wide

range but do not have the same curvature as present in the TDDS data. The

over a wide

range but do not have the same curvature as present in the TDDS data. The

show neither a plateau nor a drop towards weak fields. Compared to the

McWhorter model,

show neither a plateau nor a drop towards weak fields. Compared to the

McWhorter model,  and

and  exhibit a clear temperature activation

over the whole range of oxide fields so that their values are moved to larger time

scales relevant for NBTI.

exhibit a clear temperature activation

over the whole range of oxide fields so that their values are moved to larger time

scales relevant for NBTI. , no reasonable agreement with the measurement

data could be achieved. This discrepancy can be explained as follows: The

exponential bias dependence extends up to a voltage

, no reasonable agreement with the measurement

data could be achieved. This discrepancy can be explained as follows: The

exponential bias dependence extends up to a voltage  at which

at which  coincides with

coincides with  . In Fig.

. In Fig.  is approximately

is approximately  so

that

so

that  shows an exponential bias dependence up to this value and

becomes constant afterwards. Therefore,

shows an exponential bias dependence up to this value and

becomes constant afterwards. Therefore,  must be chosen such that

must be chosen such that  lies above the voltage range used in the measurements. This is only the

case for defects whose trap levels

lies above the voltage range used in the measurements. This is only the

case for defects whose trap levels  are situated sufficiently low. Note

that those defects are also characterized by a large

are situated sufficiently low. Note

that those defects are also characterized by a large  , which marks the

voltage where

, which marks the

voltage where  coincides with

coincides with  . After equation (

. After equation ( must equal their

must equal their  at

at  , visible as the crossings between

, visible as the crossings between  and

and  in Fig.

in Fig.  so that their emission times fall several orders of magnitude below

their corresponding capture time constants. The large difference between

so that their emission times fall several orders of magnitude below

their corresponding capture time constants. The large difference between

and

and  predicted by the Kirton model is inconsistent with the

experimental TDDS data. Additionally, a fit of the Kirton model to

predicted by the Kirton model is inconsistent with the

experimental TDDS data. Additionally, a fit of the Kirton model to  is

presented in Fig.

is

presented in Fig.  fails to

reproduce the experimentally obtained

fails to

reproduce the experimentally obtained  when a good match with

when a good match with  is

achieved.

is

achieved.

(left),

reasonable fits can be achieved for them but

(left),

reasonable fits can be achieved for them but  is predicted three orders of

magnitudes too low. Alternatively, a good agreement (right) can be obtained

for the hole emission times

is predicted three orders of

magnitudes too low. Alternatively, a good agreement (right) can be obtained

for the hole emission times  but with a strong mismatch of the capture

times

but with a strong mismatch of the capture

times  for

for  . From this it is concluded that the Kirton model

is not capable of fitting

. From this it is concluded that the Kirton model

is not capable of fitting  and

and  at the same time.

at the same time.