, which is

suspected to have a strong impact on hole capture processes in NBTI and

has therefore been phenomenologically introduced in the two-stage model

(TSM) [61].

, which is

suspected to have a strong impact on hole capture processes in NBTI and

has therefore been phenomenologically introduced in the two-stage model

(TSM) [61].

The concept of NMP has been used in a slightly modified variant termed

multiphonon field-assisted tunneling (MPFAT) [116, 115, 116, 117, 125, 55], which

was proposed for ionization of deep impurity centers. The underlying theory accounts

for the fact that the emission of charge carriers out of bulk traps is accelerated in the

presence of an electric field. This effect is eventually related to the shortened

tunneling distance through a triangular barrier when considering thermal

excitation of the charge carriers. According to theoretical calculations of

Ganichev et al. [117], it yields a field enhancement factor  , which is

suspected to have a strong impact on hole capture processes in NBTI and

has therefore been phenomenologically introduced in the two-stage model

(TSM) [61].

, which is

suspected to have a strong impact on hole capture processes in NBTI and

has therefore been phenomenologically introduced in the two-stage model

(TSM) [61].

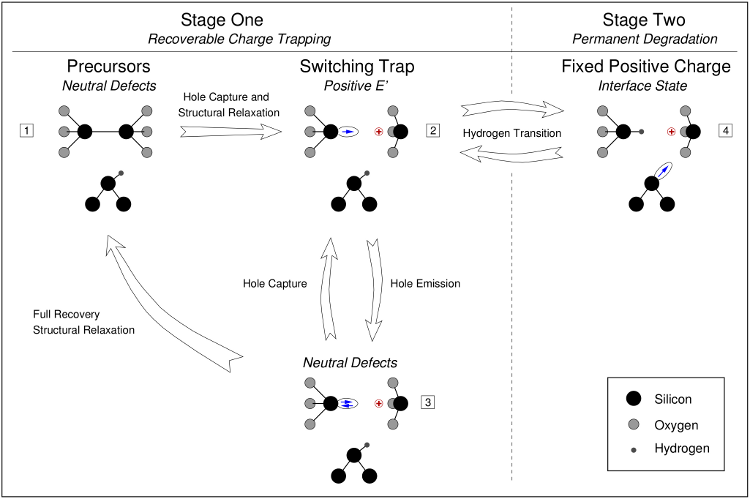

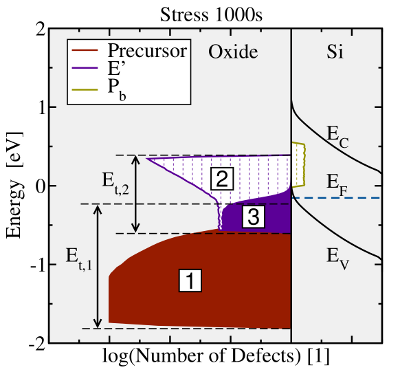

The TSM relies on the Harry-Diamond-Laboratories (HDL) [15] model but is

extended by a second stage accounting for the permanent component of NBTI (cf.

Fig. 6.3). The defect precursor, an oxygen vacancy according to the HDL model, is

capable of capturing substrate holes via the aforementioned MPFAT mechanism. The

trap level  of the precursor is located below the substrate valence band and

subject to a wide distribution due to the amorphousness of

of the precursor is located below the substrate valence band and

subject to a wide distribution due to the amorphousness of  . Upon hole

capture, the defect undergoes a transformation to an

. Upon hole

capture, the defect undergoes a transformation to an  center, which is visible in

ESR measurements [43]. In this new configuration, it features a

center, which is visible in

ESR measurements [43]. In this new configuration, it features a  dangling bond

associated with a defect level

dangling bond

associated with a defect level  within or close to within the substrate bandgap

in accordance to [162]. The level shift from

within or close to within the substrate bandgap

in accordance to [162]. The level shift from  to

to  arises from the change to

a new ‘stable’ defect configuration, namely the

arises from the change to

a new ‘stable’ defect configuration, namely the  dangling bond. In the

dangling bond. In the  center configuration, the defect can be repeatedly charged and discharged by

electrons tunneling in or out of its dangling bond. The associated switching

behavior1

is in agreement with the experimental observations made in electrical

measurements [15, 16]. Only in the neutral state

center configuration, the defect can be repeatedly charged and discharged by

electrons tunneling in or out of its dangling bond. The associated switching

behavior1

is in agreement with the experimental observations made in electrical

measurements [15, 16]. Only in the neutral state  , in which the

, in which the  dangling bond

is doubly occupied by an electron, the

dangling bond

is doubly occupied by an electron, the  center can be annealed, thereby becoming

an oxygen vacancy again.

center can be annealed, thereby becoming

an oxygen vacancy again.

and

and  . From

the neutral charge state

. From

the neutral charge state  , the defect can undergo structural relaxation over a

thermal barrier and arrives at its initial configuration. The second stage gives

an explanation for the permanent component, which is attributed to a hydrogen

transition from state

, the defect can undergo structural relaxation over a

thermal barrier and arrives at its initial configuration. The second stage gives

an explanation for the permanent component, which is attributed to a hydrogen

transition from state  to

to  . This transition fixes the positive charge (red

plus sign) in the defect and creates a new interface state (ellipse with one or

two blue arrows).

. This transition fixes the positive charge (red

plus sign) in the defect and creates a new interface state (ellipse with one or

two blue arrows).The second stage involves an amphoteric trap, most probably a  center, which

has been found to interact with the switching trap as observed in irradiation

experiments [43]. That is, a hydrogen is detached from an interfacial

center, which

has been found to interact with the switching trap as observed in irradiation

experiments [43]. That is, a hydrogen is detached from an interfacial  -

- bond

and leaves behind a

bond

and leaves behind a  center. In a subsequent reaction, it saturates the

dangling bond of the

center. In a subsequent reaction, it saturates the

dangling bond of the  center. This stage fixes the positive charge at

the oxide defect and creates a new interface state, whose charge state is

controlled by the substrate Fermi level. Since the hydrogen transition is

assumed to last much longer than the hole capture or emission process, this

stage corresponds to the permanent or slowly recoverable component of

NBTI.

center. This stage fixes the positive charge at

the oxide defect and creates a new interface state, whose charge state is

controlled by the substrate Fermi level. Since the hydrogen transition is

assumed to last much longer than the hole capture or emission process, this

stage corresponds to the permanent or slowly recoverable component of

NBTI.

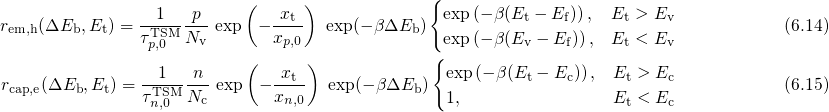

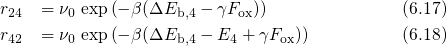

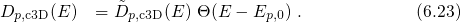

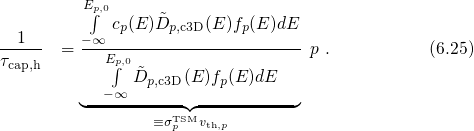

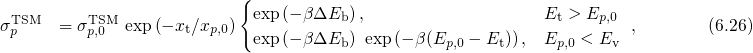

Mathematically, the dynamics of this complex mechanism are described by the set of the following rate equations:

The subscript of

of  stands for the state according to the numbering in Fig. 6.3.

The transition rates are denoted as

stands for the state according to the numbering in Fig. 6.3.

The transition rates are denoted as  , with

, with  and

and  as the initial and the final

states, respectively. The rate

as the initial and the final

states, respectively. The rate  is derived from the SRH equations (2.69),

in which the empirical enhancement factor

is derived from the SRH equations (2.69),

in which the empirical enhancement factor  for the MPFAT

transition2

for the MPFAT

transition2

has been phenomenologically introduced. Then the transition rates read

with The quantity

has been phenomenologically introduced. Then the transition rates read

with The quantity  is the equivalent of

is the equivalent of  in the TSM and can be calculated

according to equation (2.76). The barriers

in the TSM and can be calculated

according to equation (2.76). The barriers  and

and  are defined

analogously to the barrier

are defined

analogously to the barrier  in Fig. 2.5. Therefore, they corresponds to the

barrier component, which must be overcome in both directions of the transitions

in Fig. 2.5. Therefore, they corresponds to the

barrier component, which must be overcome in both directions of the transitions

and

and  , respectively (cf. Fig 2.5). For the transitions between the states

, respectively (cf. Fig 2.5). For the transitions between the states

and

and  the capture and emission of electrons as well as holes are taken into account.

the capture and emission of electrons as well as holes are taken into account.

) is represented by the rate

) is represented by the rate  , which is

modeled by a structural relaxation over a thermal barrier

, which is

modeled by a structural relaxation over a thermal barrier  .

.

denotes the attempt frequency, which is usually in the order of

denotes the attempt frequency, which is usually in the order of  . The

hydrogen transition

. The

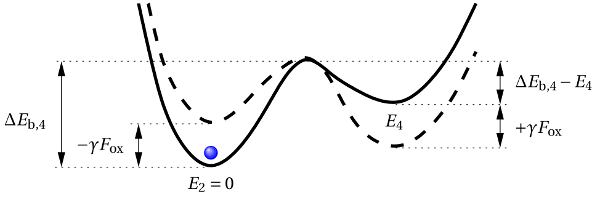

hydrogen transition  is modeled assuming a field-dependent thermal barrier, as

shown in Fig. 6.4.

is modeled assuming a field-dependent thermal barrier, as

shown in Fig. 6.4.

) but lowers that of state 4 (

) but lowers that of state 4 ( ). Since the interfacial

). Since the interfacial

-

- bonds are associated with a dipole moment, the shift of the energy

minima depends linearly on the oxide field with a proportionality constant of

bonds are associated with a dipole moment, the shift of the energy

minima depends linearly on the oxide field with a proportionality constant of

. The applied oxide field gives rise to a reduced forward barrier (

. The applied oxide field gives rise to a reduced forward barrier ( ) and

an increased reverse barrier (

) and

an increased reverse barrier ( ). Without loss of generality, the value of

). Without loss of generality, the value of

is set to zero.

is set to zero.The following simulations are based on the same numerical scheme as has

been presented in Section 3.2 and are used for the ETM and the LSM in

Chapter 4 and 5. Each representative trap in this scheme is characterized by its

individual set of defect levels and barriers. The generated random numbers are

homogeneously distributed for  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  while they follow a

Fermi-derivative (Gaussian-like) distribution [90] for

while they follow a

Fermi-derivative (Gaussian-like) distribution [90] for  and

and  . The

remaining quantities including

. The

remaining quantities including  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  , and

, and  are assumed to be

single-valued.

are assumed to be

single-valued.

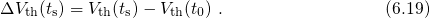

In contrast to previous models, oxide charges (state 2) as well as interface traps

(state 4) are incorporated into the TSM so that two states must be considered for

the calculation of  . It is important to note that only a part of the

overall degradation during stress is observed within the experimental time

window. As demonstrated in Fig. 6.5, a large fraction already occurs before the

beginning of the OTF measurement (

. It is important to note that only a part of the

overall degradation during stress is observed within the experimental time

window. As demonstrated in Fig. 6.5, a large fraction already occurs before the

beginning of the OTF measurement ( ) and only a part of the

) and only a part of the  degradation can be monitored by this technique (cf. Section 1.3.2). As a

consequence, the measured threshold voltage shift must be calculated as

degradation can be monitored by this technique (cf. Section 1.3.2). As a

consequence, the measured threshold voltage shift must be calculated as

so that

only the tails of the real recovery curve can be assessed experimentally.

so that

only the tails of the real recovery curve can be assessed experimentally.

shift from the recorded drain current during the relaxation

phase. Note that OTF only assesses the change of threshold voltage referred to

the first measurement point, but disregards the degradation accumulated before.

Analogously, the NBTI recovery may start already before

shift from the recorded drain current during the relaxation

phase. Note that OTF only assesses the change of threshold voltage referred to

the first measurement point, but disregards the degradation accumulated before.

Analogously, the NBTI recovery may start already before  but the MSM

technique can only monitor the tails of the degradation curves.

but the MSM

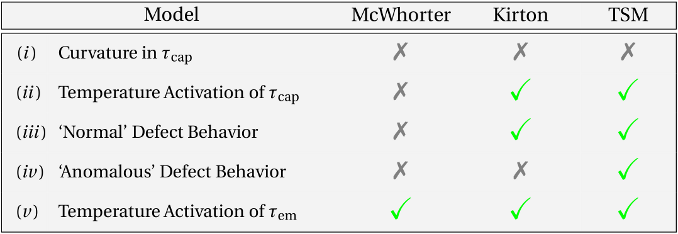

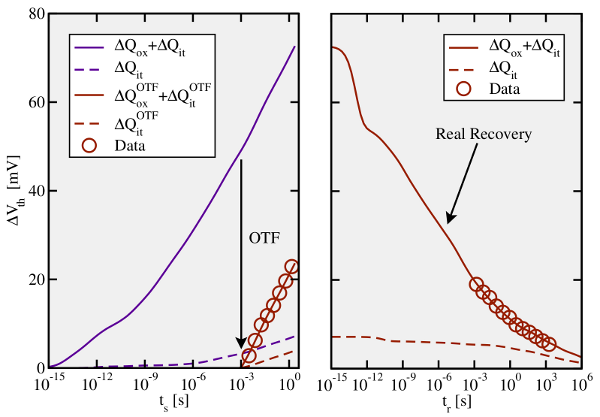

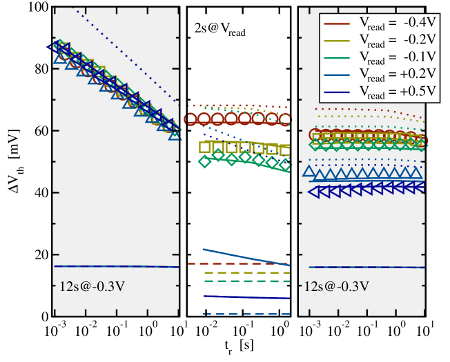

technique can only monitor the tails of the degradation curves.The TSM [61] has been compared to a large set of measurement data, including

various combinations of stress voltages and temperatures. For illustration, a fit to the

eMSM (cf. Section 1.4) data at  is depicted in Fig. 6.6. The findings of this

model are evaluated in the following:

is depicted in Fig. 6.6. The findings of this

model are evaluated in the following:

) is determined and no sign of saturation appears until

) is determined and no sign of saturation appears until  .

Detrapping during relaxation extends over the whole experimental time

window ranging from

.

Detrapping during relaxation extends over the whole experimental time

window ranging from  to

to  .

.

follows a logarithmic time behavior during the whole stress

phase.

follows a logarithmic time behavior during the whole stress

phase.

where the

where the  curve starts to level off. This is

due to the fact that the TSM also accounts for the permanent component

of NBTI.

curve starts to level off. This is

due to the fact that the TSM also accounts for the permanent component

of NBTI.

during the stress and the relaxation phase

exhibit a ratio of

during the stress and the relaxation phase

exhibit a ratio of  in agreement with [61]. This asymmetry is

demonstrated by the temporal change of the trap occupancy in Fig. 6.6 (right).

After the level shift from

in agreement with [61]. This asymmetry is

demonstrated by the temporal change of the trap occupancy in Fig. 6.6 (right).

After the level shift from  to

to  , when the defect transforms from an

oxygen vacancy to an

, when the defect transforms from an

oxygen vacancy to an  center, the trap level

center, the trap level  lies closer to the

substrate valence bandedge than

lies closer to the

substrate valence bandedge than  . This results in higher trapping rates

for hole capture (

. This results in higher trapping rates

for hole capture ( ) and emission (

) and emission ( ) so that the subsystem

of states

) so that the subsystem

of states  and

and  is only weakly affected by

is only weakly affected by  during recovery.

Therefore, this reduced system is close to equilibrium, meaning that

during recovery.

Therefore, this reduced system is close to equilibrium, meaning that

. Then the occupation

. Then the occupation  is given by and can be interpreted as the electron occupancy

is given by and can be interpreted as the electron occupancy  of the

of the  center with

the defect level

center with

the defect level  . According to the above equation, the defect occupancy in

the whole defect system of the TSM follows the substrate Fermi level, which

thus controls the annealing rate

. According to the above equation, the defect occupancy in

the whole defect system of the TSM follows the substrate Fermi level, which

thus controls the annealing rate  and can slow down the recovery. Due to

this ‘occupancy effect’, the TSM is able to capture the asymmetry between

stress and relaxation.

and can slow down the recovery. Due to

this ‘occupancy effect’, the TSM is able to capture the asymmetry between

stress and relaxation.

device (symbols) for 8 different stress voltages at a

temperature of

device (symbols) for 8 different stress voltages at a

temperature of  . The field acceleration as well as the asymmetry between

stress and relaxation have been nicely reproduced. Right: Averaged trap

occupancy during stress and recovery for a single trap. The dotted lines refer

to oxide defects in state

. The field acceleration as well as the asymmetry between

stress and relaxation have been nicely reproduced. Right: Averaged trap

occupancy during stress and recovery for a single trap. The dotted lines refer

to oxide defects in state  or

or  , while the solid lines include the positively

charged defects (state

, while the solid lines include the positively

charged defects (state  ) only. The ratio between the slope of the stress (

) only. The ratio between the slope of the stress ( )

and the relaxation (

)

and the relaxation ( ) curve yields

) curve yields  , as observed experimentally

in [61].

, as observed experimentally

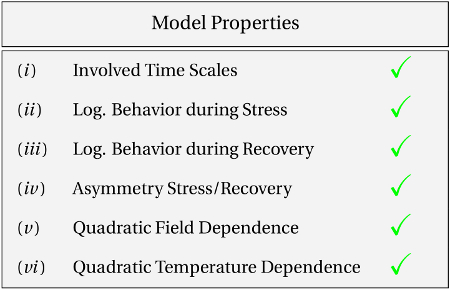

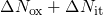

in [61].The TSM is found to satisfy all criteria of Table 6.2 and therefore seems to properly

describe NBTI degradation. Besides that, it also agrees well with the observation of a

field-dependent recovery, which is demonstrated by the measurements shown in

Fig. 6.7. Due to the occupancy effect, the substrate Fermi level  controls the

portion of neutral

controls the

portion of neutral  centers (state 3) which can return to state

centers (state 3) which can return to state  by structural

relaxation and contribute to the NBTI recovery. Interestingly, this field dependence is

compatible with the finding that the emission times of ‘anomalous defects’ are

field-sensitive.

by structural

relaxation and contribute to the NBTI recovery. Interestingly, this field dependence is

compatible with the finding that the emission times of ‘anomalous defects’ are

field-sensitive.

under the same conditions (

under the same conditions ( ,

,  ). The following

recovery phase (left and right panel) was interrupted for a period of time during

which

). The following

recovery phase (left and right panel) was interrupted for a period of time during

which  was switched from the recovery voltage of

was switched from the recovery voltage of  to

to  for

for

(middle panel). The experimental data are marked by symbols, while the

simulations are represented by lines (dotted:

(middle panel). The experimental data are marked by symbols, while the

simulations are represented by lines (dotted:  , solid:

, solid:  due to

due to

, dashed:

, dashed:  due to

due to  ). The measurements demonstrate

that the recovery is clearly affected by variations of the recovery bias. This

effect is reminiscent of the field-dependent emission times seen in TDDS. The

agreement of the simulations with the measurements shows that the TSM can

explain the field-dependent NBTI recovery.

). The measurements demonstrate

that the recovery is clearly affected by variations of the recovery bias. This

effect is reminiscent of the field-dependent emission times seen in TDDS. The

agreement of the simulations with the measurements shows that the TSM can

explain the field-dependent NBTI recovery.The distributions of trap levels obtained from the model calibration are depicted in

Fig. 6.8. The trap levels  of the precursors (state

of the precursors (state  ) are uniformly distributed

between

) are uniformly distributed

between  and

and  in qualitative agreement with the values in [39].

The defects located the highest have also the highest substrate hole capture rates

in qualitative agreement with the values in [39].

The defects located the highest have also the highest substrate hole capture rates

and therefore have already been transformed

and therefore have already been transformed  centers (states

centers (states  and

and  )

after a stress time of

)

after a stress time of  . In this new configuration, they feature a trap

level

. In this new configuration, they feature a trap

level  in the range between

in the range between  and

and  in qualitative

agreement with the values published in [39]. According to equation (6.21), the

occupancy of the

in qualitative

agreement with the values published in [39]. According to equation (6.21), the

occupancy of the  levels is determined by the substrate Fermi energy

and thus the number of neutralized defects in the

levels is determined by the substrate Fermi energy

and thus the number of neutralized defects in the  center configuration

(state

center configuration

(state  ) increases with a lower energies. Since only defects in this state

transformed to a precursor (state

) increases with a lower energies. Since only defects in this state

transformed to a precursor (state  ) again, the number of traps in state

) again, the number of traps in state  diminished towards the substrate Fermi energy (cf. Fig. 6.8). The donor

levels of the interface states have been assumed to be uniformly distributed

and are located within the lower part of the substrate bandgap consistent

with [64].

diminished towards the substrate Fermi energy (cf. Fig. 6.8). The donor

levels of the interface states have been assumed to be uniformly distributed

and are located within the lower part of the substrate bandgap consistent

with [64].

. The numbers in the white filled boxes denote the state of the defects.

The area in the plain red color gives the number of precursors (state

. The numbers in the white filled boxes denote the state of the defects.

The area in the plain red color gives the number of precursors (state  ) with

the trap level

) with

the trap level  . The rest of the defects is in the

. The rest of the defects is in the  center configuration,

in which they can be positively charged (purple striped pattern) or neutralized

(plain purple color) and have a trap level of

center configuration,

in which they can be positively charged (purple striped pattern) or neutralized

(plain purple color) and have a trap level of  . The occupied (plain) and

unoccupied (striped) interface states are depicted as beige areas. The beige

striped area gives the density of interface states originating from the

. The occupied (plain) and

unoccupied (striped) interface states are depicted as beige areas. The beige

striped area gives the density of interface states originating from the  centers.

centers.So far, classical calculations of the band diagram have been performed to obtain the

interface quantities, such as the position of the bandedges ( ,

,  ), the Fermi

level (

), the Fermi

level ( ), and the electric field (

), and the electric field ( ) within the dielectric. These quantities enter

the expressions of the rates and will significantly alter them due to their exponential

dependences. However, the SRH rates (6.9) used in Section 6.3.1 are valid for a

three-dimensional electron gas [55] but this assumption breaks down for an

inversion layer of MOS structures. In the one-dimensional triangular potential

well in the channel, quasi-bound states build up and form subbands, which

correspond to the new initial or final energy levels for the charge carriers

undergoing an NMP transitions. The quantum mechanical transition rates are

obtained following the derivation in Section 2.5.2 but using the DOS for

one-dimensionally confined holes. Then the rate equation (2.59) modifies to

) within the dielectric. These quantities enter

the expressions of the rates and will significantly alter them due to their exponential

dependences. However, the SRH rates (6.9) used in Section 6.3.1 are valid for a

three-dimensional electron gas [55] but this assumption breaks down for an

inversion layer of MOS structures. In the one-dimensional triangular potential

well in the channel, quasi-bound states build up and form subbands, which

correspond to the new initial or final energy levels for the charge carriers

undergoing an NMP transitions. The quantum mechanical transition rates are

obtained following the derivation in Section 2.5.2 but using the DOS for

one-dimensionally confined holes. Then the rate equation (2.59) modifies to

does not enter this derivation

and consequently the DOS can be expressed as

does not enter this derivation

and consequently the DOS can be expressed as

can be identified as

can be identified as

(cf. Fig. 6.9).

(cf. Fig. 6.9).

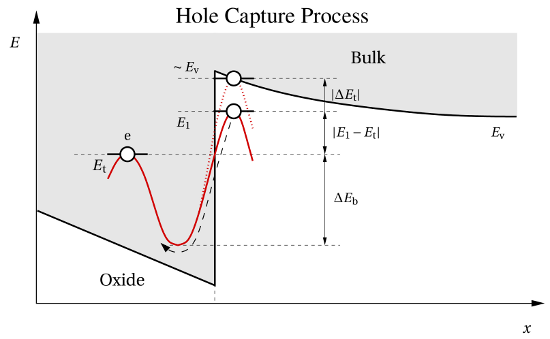

corresponds to the first bound state. Inserting the modified cross section

in equation (2.65) and (2.66) yields and

corresponds to the first bound state. Inserting the modified cross section

in equation (2.65) and (2.66) yields and

when quantum confinement

is taken into account. The shift of the initial energy level from

when quantum confinement

is taken into account. The shift of the initial energy level from  to

to  reduces the corresponding NMP barriers (red lines) and thus enhances the hole

capture rates. Note that the energy difference between

reduces the corresponding NMP barriers (red lines) and thus enhances the hole

capture rates. Note that the energy difference between  and

and  varies with

the oxide field and thus affects the field dependence of

varies with

the oxide field and thus affects the field dependence of  and

and  .

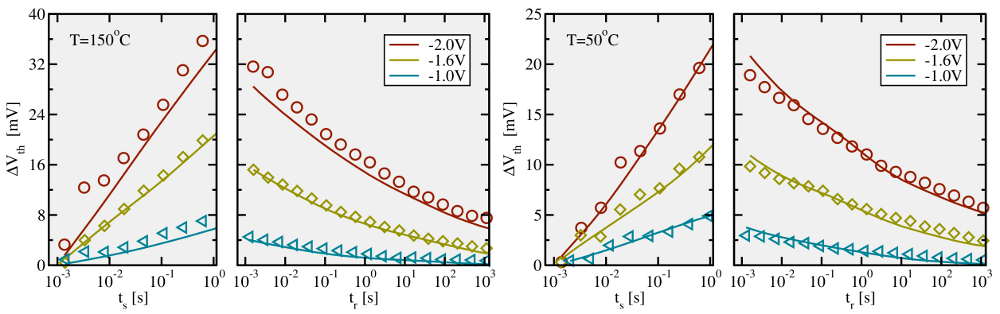

.These rates have been used to incorporate the aforementioned quantum effects into

the TSM, which has been evaluated against the same set of experimental data. For a

proper comparison with the classical variant of TSM, only the NMP parameters

( ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  ) have been optimized while all other parameters

have been held fixed. The simulated degradation curves show a good agreement with

experimental data (see Fig. 6.10) so that the quantum mechanically refined variant

of the TSM still fulfills all criteria listed in Table 6.2. It is noted here that

these simulations yield an the uppermost trap levels

) have been optimized while all other parameters

have been held fixed. The simulated degradation curves show a good agreement with

experimental data (see Fig. 6.10) so that the quantum mechanically refined variant

of the TSM still fulfills all criteria listed in Table 6.2. It is noted here that

these simulations yield an the uppermost trap levels  , which have been

shifted downwards by about the same energy as the separation of

, which have been

shifted downwards by about the same energy as the separation of  and

and

(ranging between

(ranging between  and

and  ). This can be explained when

considering that, first,

). This can be explained when

considering that, first,  is replaced

is replaced  in the rate equations (6.27) and

(6.28) and, second, the NMP barrier for hole capture is reduced by this

energy difference. From this it follows that also the trap levels

in the rate equations (6.27) and

(6.28) and, second, the NMP barrier for hole capture is reduced by this

energy difference. From this it follows that also the trap levels  must

be shifted down by approximately the same energy in order to obtain hole

capture rates of an equal magnitude. In summary, it has been assured that

also the quantum mechanically refined variant of the TSM can explain the

NBTI data and must therefore be considered as a reasonable NBTI model.

must

be shifted down by approximately the same energy in order to obtain hole

capture rates of an equal magnitude. In summary, it has been assured that

also the quantum mechanically refined variant of the TSM can explain the

NBTI data and must therefore be considered as a reasonable NBTI model.

is

subjected to two different temperatures (

is

subjected to two different temperatures ( left panels,

left panels,  tight

panels) and three different gate voltages for

tight

panels) and three different gate voltages for  during the first phase termed

trapping/stress (left hand side). After the gate voltage is removed, the second

phase called detrapping/relaxation phase (right-hand side) sets in. Symbols

mark measurement data while solid lines belong to simulation data. Note that

the temperature and field dependence is well reproduced simultaneously for

relaxation phase. The slight tendency of the simulations to underestimate the

measurements at high stress temperatures during the stress phase appear in

the classical as well as in the quantum mechanical simulations. They may be

traced back to the mobility degradation of the drain current during the MSM

measurements [26].

during the first phase termed

trapping/stress (left hand side). After the gate voltage is removed, the second

phase called detrapping/relaxation phase (right-hand side) sets in. Symbols

mark measurement data while solid lines belong to simulation data. Note that

the temperature and field dependence is well reproduced simultaneously for

relaxation phase. The slight tendency of the simulations to underestimate the

measurements at high stress temperatures during the stress phase appear in

the classical as well as in the quantum mechanical simulations. They may be

traced back to the mobility degradation of the drain current during the MSM

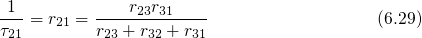

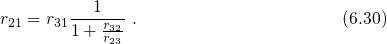

measurements [26].The criteria in Table 4.1 have been successfully satisfied by the TSM. With this

respect, the TSM should be regarded as model qualified to describe NBTI. However,

these criteria only evaluate the degradation produced by an ensemble of defects but

do not consider whether the behavior of a single defect is correctly reproduced. For

this reason, the TSM will be investigated using the time constant plots in the

following. Since the TDDS measurements cannot capture the permanent component

of NBTI, the transition state diagram must be reduced to stage one. This means that

the equation (6.8) and the rates  and

and  in equation (6.6) must be omitted.

Since the trap level

in equation (6.6) must be omitted.

Since the trap level  is assumed to lie closer to the valence band edge

than

is assumed to lie closer to the valence band edge

than  , the accociated rate

, the accociated rate  and

and  are much larger than

are much larger than  .

Thus the fast switching between state

.

Thus the fast switching between state  and

and  produces noise, which is

undesired for the analysis of

produces noise, which is

undesired for the analysis of  in the time constant plots. Therefore, a

compact rate expression for the transition

in the time constant plots. Therefore, a

compact rate expression for the transition  is sought. One can

calculate the corresponding emission time

is sought. One can

calculate the corresponding emission time  as the mean first passage time

in continuous time Markov chain theory [131] (discussed in Section 3.2).

as the mean first passage time

in continuous time Markov chain theory [131] (discussed in Section 3.2).

and

and  , the above expression can be simplified to

, the above expression can be simplified to

,

,

, and

, and  can be neglected. This reduced variant of the TSM is fitted against the TDDS data and will be

evaluated according to the list of criteria established in Section 1.3.4.

can be neglected. This reduced variant of the TSM is fitted against the TDDS data and will be

evaluated according to the list of criteria established in Section 1.3.4.

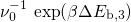

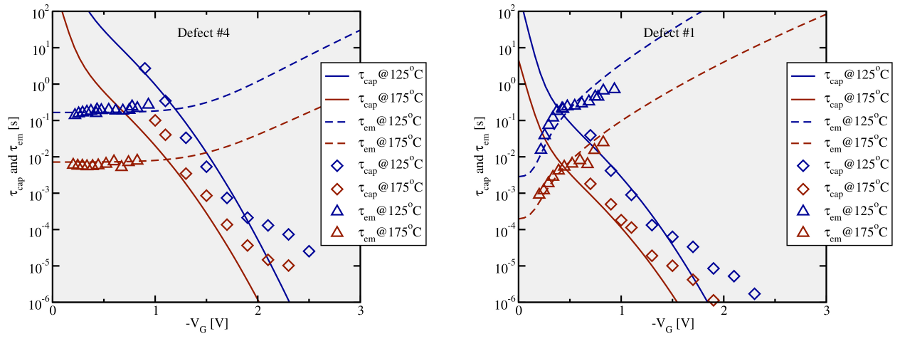

in the time constant plot of Fig. 6.11 has a wrong

curvature. This can be traced back to the fact that

in the time constant plot of Fig. 6.11 has a wrong

curvature. This can be traced back to the fact that  is proportional

to

is proportional

to  according to equation (6.31).

according to equation (6.31).

.

.

as demonstrated in Fig. 6.11.

However, this is only true for defects with a trap level

as demonstrated in Fig. 6.11.

However, this is only true for defects with a trap level  above

above

. In this case,

. In this case,  approximates to

approximates to  and

and  is given by

is given by

.

.

if

if  is located slightly

below

is located slightly

below  at the relaxation voltage. Then the field dependence is caused

by the term

at the relaxation voltage. Then the field dependence is caused

by the term  in equation (6.32).

in equation (6.32).

is thermally-activated.

is thermally-activated.

, the

TSM can explain both defect behaviors. However, it does not give the correct

curvature of

, the

TSM can explain both defect behaviors. However, it does not give the correct

curvature of  due to the field enhancement factor.

due to the field enhancement factor.As demonstrated in the previous section, the TSM is indeed an important

improvement of the NBTI model. Regarding the time constant plots (cf. Table 6.3),

the introduction of the state  gives an explanation for ‘normal’ as well

as the ‘anomalous’ defect behavior. However, the TSM predicts a wrong

curvature of

gives an explanation for ‘normal’ as well

as the ‘anomalous’ defect behavior. However, the TSM predicts a wrong

curvature of  and thus cannot be reconciled with the TDDS data. As a

consequence, it can be concluded that the TSM performs well for stress

and relaxation curves but fails to describe the behavior of single defects.

and thus cannot be reconciled with the TDDS data. As a

consequence, it can be concluded that the TSM performs well for stress

and relaxation curves but fails to describe the behavior of single defects.