4.2 Elastic Tunneling

Tewksbury[23] assumed elastic tunneling of electrons and holes into and out of oxide

defects as the mechanism responsible for charge trapping. The use of his model

has been suggested by Huard et al. [58] in order to explain the recoverable

part of the NBTI degradation. In this section, Tewksbury’s model will be

reviewed, extended for an application of present-day devices with small gate

thicknesses, and referred to as the elastic tunneling model (ETM) in the

following.

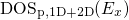

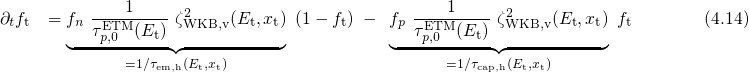

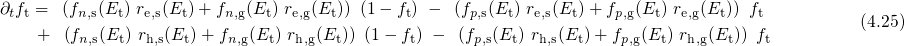

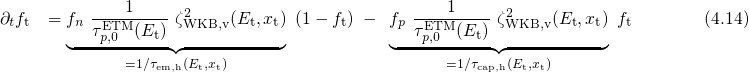

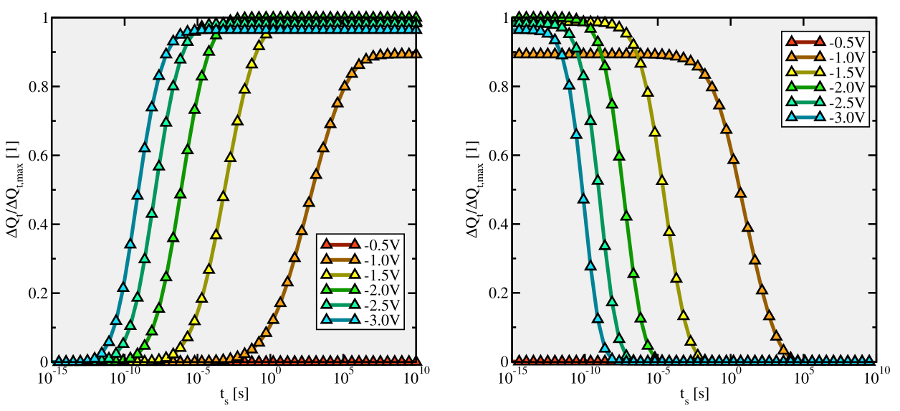

The approach applied in this thesis relies on rate equations for tunneling into one

trap. The required rate expressions  and

and  are given by the equations

(2.45) and (2.46), which already incorporate all elastic tunneling transitions between

one trap and the numerous band states. Due to their analytical complexity, these rate

equations are solved numerically using the numerical iteration scheme presented in

Section 3.2. The used simple first-order partial differential equation reads

are given by the equations

(2.45) and (2.46), which already incorporate all elastic tunneling transitions between

one trap and the numerous band states. Due to their analytical complexity, these rate

equations are solved numerically using the numerical iteration scheme presented in

Section 3.2. The used simple first-order partial differential equation reads

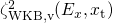

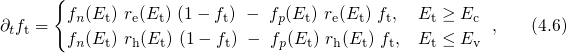

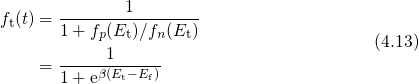

with the electron and hole trapping times approximated as The electron ( ) and hole (

) and hole ( ) occupancy are defined as with

) occupancy are defined as with  being the Fermi-Dirac distribution. The above rate equation features the

same structure as that of equation (4.1). Therefore, the same mathematical

implications as for the phenomenological model hold true for the ETM.

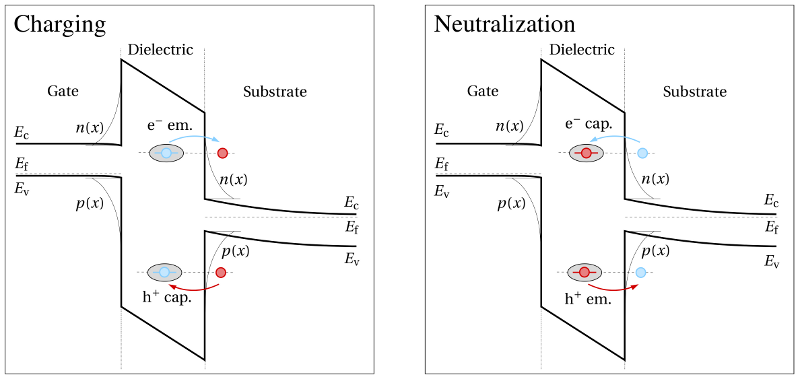

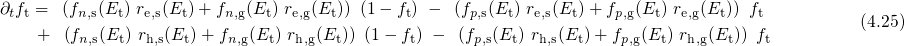

Furthermore, equation (4.6) covers all four basic transitions illustrated Fig. 4.2 so

that it can be viewed as a comprehensive description of elastic tunneling in

MOSFETs.

being the Fermi-Dirac distribution. The above rate equation features the

same structure as that of equation (4.1). Therefore, the same mathematical

implications as for the phenomenological model hold true for the ETM.

Furthermore, equation (4.6) covers all four basic transitions illustrated Fig. 4.2 so

that it can be viewed as a comprehensive description of elastic tunneling in

MOSFETs.

4.2.1 The Behavior of A Single Trap

In this chapter, the investigations are focused on NBTI in pMOSFETs since these

devices attract a large industrial interest at the moment. Therefore, only hole

tunneling from the substrate valence band will be addressed in the following.

Naturally, the basic statements will also remain valid for electron tunneling in the

case of PBTI in nMOSFETs and for the different dielectric materials used in modern

device technologies. For the trapping dynamics,  and

and  in

in

and

and  of equation (4.6) are the most sensitive factors.

These quantities determine the basic properties of the ETM and will be discussed in

detail in this section.

of equation (4.6) are the most sensitive factors.

These quantities determine the basic properties of the ETM and will be discussed in

detail in this section.

The trapping dynamics are described by the rate equation (4.6), which has

the same forward  and reverse

and reverse  rate considering hole trapping

(

rate considering hole trapping

( ).

This special form implies that the occupancy of the trap

).

This special form implies that the occupancy of the trap  equilibrates to that of

the valence band states at the same energy

equilibrates to that of

the valence band states at the same energy  . For steady state conditions,

. For steady state conditions,  reads

reads

where  and

and  take the role of

take the role of  and

and  in (4.2), respectively. The

above equation shows that the trap occupancy is eventually governed by the

relative magnitude of

in (4.2), respectively. The

above equation shows that the trap occupancy is eventually governed by the

relative magnitude of  and

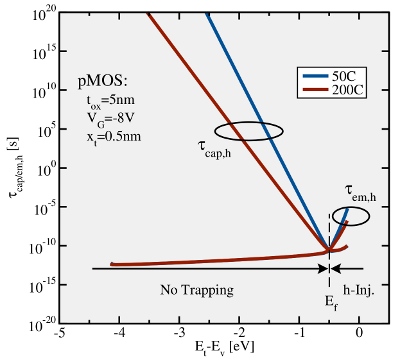

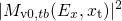

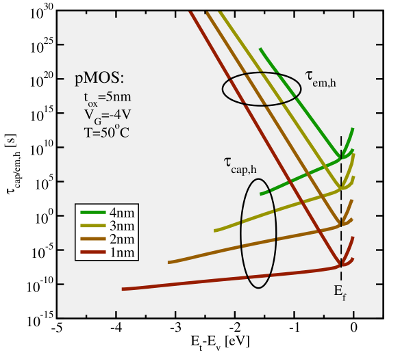

and  . Both time constants are most

strongly affected by the exponential decay of the Fermi-Dirac distribution. This

dependence is pointed out in Fig. 4.3, where the hole capture and emission

times are plotted with respect to the trap energy

. Both time constants are most

strongly affected by the exponential decay of the Fermi-Dirac distribution. This

dependence is pointed out in Fig. 4.3, where the hole capture and emission

times are plotted with respect to the trap energy  . In the region below

. In the region below

, the hole occupancy

, the hole occupancy  decreases by several orders of magnitude per

decreases by several orders of magnitude per

so that the hole capture times

so that the hole capture times  by far exceed the corresponding

emission times

by far exceed the corresponding

emission times  . Therefore, no effective hole trapping can take place in

this region, irrespectively of the temperature. By contrast above

. Therefore, no effective hole trapping can take place in

this region, irrespectively of the temperature. By contrast above  , the

exponential decay of

, the

exponential decay of  causes an increase in the hole emission times

causes an increase in the hole emission times  ,

which gives rise to hole trapping there. That is,

,

which gives rise to hole trapping there. That is,  can be regarded as a

demarcation energy between both regions. This fact is also reflected in the

equilibrium solution (4.12) when using the definitions of

can be regarded as a

demarcation energy between both regions. This fact is also reflected in the

equilibrium solution (4.12) when using the definitions of  and

and  .

.

As a consequence, the trap occupancy is governed by the position of the substrate Fermi level

in equilibrium.

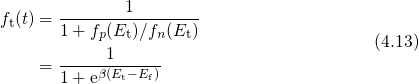

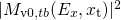

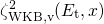

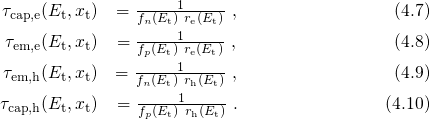

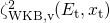

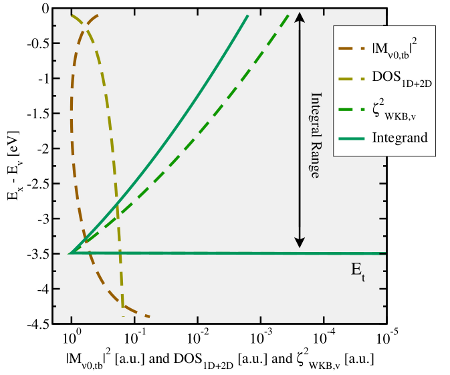

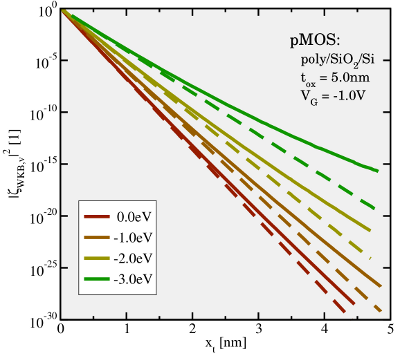

As mentioned before, the most sensitive factors in the tunneling rates of equation

(4.6) are the Fermi-Dirac distribution and the WKB factor. In contrast to  and

and

, the latter is a function of

, the latter is a function of  and cannot be taken out of the integrals in the

rate expressions (2.45) and (2.46). As shown in Fig. 4.4,

and cannot be taken out of the integrals in the

rate expressions (2.45) and (2.46). As shown in Fig. 4.4,  and

and

, the matrix element without the WKB factor, are subject

to small variations so that they weakly affect the tunneling rates. Since

the WKB factor falls off quickly with increasing

, the matrix element without the WKB factor, are subject

to small variations so that they weakly affect the tunneling rates. Since

the WKB factor falls off quickly with increasing  , the integral (2.46)

delivers the largest contribution close to the trap level

, the integral (2.46)

delivers the largest contribution close to the trap level  . Therefore, it

makes sense to approximate the rate integral (2.46) by dividing it through

. Therefore, it

makes sense to approximate the rate integral (2.46) by dividing it through

and define the resulting expression as

and define the resulting expression as  . This new

quantity incorporates the weak dependences on

. This new

quantity incorporates the weak dependences on  while the sensitive factors,

namely

while the sensitive factors,

namely  or

or  and the WKB factor, are separated. Due to the small variations

of

and the WKB factor, are separated. Due to the small variations

of  and

and  ,

,  shows small changes with

shows small changes with

compared to

compared to  and

and  (see Fig. 4.5). This fact justifies

approximations[23, 160, 106, 105], in which

(see Fig. 4.5). This fact justifies

approximations[23, 160, 106, 105], in which  as a prefactor of the WKB

factor is approximated as a constant. Using the above definitions, the rate equation

for holes reads:

as a prefactor of the WKB

factor is approximated as a constant. Using the above definitions, the rate equation

for holes reads:

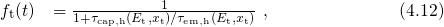

For the time evolution of charge trapping,  becomes the essential

factor (cf. Fig. 4.6). It shows an exponential decay with increasing trap depth, which

results in a shift of

becomes the essential

factor (cf. Fig. 4.6). It shows an exponential decay with increasing trap depth, which

results in a shift of  and

and  towards larger times (cf. Fig. 4.7). Note that the

energy of the tunneling charge carrier also impacts the WKB factor and the capture

and the emission times. Since the energy dependence of the WKB factor enters

both the capture and the emission times, their relative magnitude remains

unaffected and the above argumentation of

towards larger times (cf. Fig. 4.7). Note that the

energy of the tunneling charge carrier also impacts the WKB factor and the capture

and the emission times. Since the energy dependence of the WKB factor enters

both the capture and the emission times, their relative magnitude remains

unaffected and the above argumentation of  as a demarcation energy remains

valid.

as a demarcation energy remains

valid.

In conclusion, the following findings have been made: The equilibrium charge state of

an oxide defect is directly determined by the Fermi level in the substrate. When  is situated above

is situated above  , the defect will capture a hole if the defect is initially occupied

by an electron. Vice versa, positively charged defects with

, the defect will capture a hole if the defect is initially occupied

by an electron. Vice versa, positively charged defects with  below

below  will

emit their holes. However, this relationship does not make any statement

about the time point when the tunneling transitions occur. This is solely

given by the respective capture (

will

emit their holes. However, this relationship does not make any statement

about the time point when the tunneling transitions occur. This is solely

given by the respective capture ( ) or emission (

) or emission ( ) time constant.

The actual trapping times are given by the WKB factor, which predicts

increasing capture (

) time constant.

The actual trapping times are given by the WKB factor, which predicts

increasing capture ( ) and emission (

) and emission ( ) times for larger tunneling

distances.

) times for larger tunneling

distances.

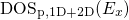

4.2.2 Spatially and Energetically Distributed Traps

In the previous sections, only the behavior of single traps has been addressed but

NBTI is actually caused by charging or discharging of a multitude of defects. This

means that the degradation has to be understood as a superposition of several

trapping events. It must be considered that the individual defects differ in their

properties, such as their spatial depth and their energetical position within the oxide

bandgap. The defects in this model are assumed to be bulk traps, which are

scattered across the whole dielectric. The distribution in the trap levels

can be attributed to variations in bond length and angles, which impact

the energy levels of the defect orbitals according to quantum mechanical

considerations[161, 162, 23]. Therefore, large variances up to a few electron Volts

have been assumed in the ETM. However, the defect levels of the hydrogen

interstitial[163] and the oxygen vacancy[164, 165] are found to have a spread

below  . Hence, distributions of energy levels with a spread larger

than

. Hence, distributions of energy levels with a spread larger

than  seem to be unrealistic and must be verified by detailed atomistic

investigations.

seem to be unrealistic and must be verified by detailed atomistic

investigations.

The following simulations, unless otherwise stated, are carried out on a pMOSFET

( ) with a strongly doped p-poly gate (

) with a strongly doped p-poly gate ( ) on

top of a

) on

top of a  thick

thick  layer. The traps in the dielectric are uniformly

distributed in space while their corresponding levels span a range from

layer. The traps in the dielectric are uniformly

distributed in space while their corresponding levels span a range from  to

to  below

below  . The operation temperature is

. The operation temperature is  so that this

value lies in the center of the temperature range relevant for NBTI. For

simplicity, only charge injection from the valence band has been taken into

account. Nevertheless, this does not affect the general findings of the model

discussion.

so that this

value lies in the center of the temperature range relevant for NBTI. For

simplicity, only charge injection from the valence band has been taken into

account. Nevertheless, this does not affect the general findings of the model

discussion.

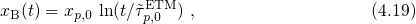

4.2.3 Time Behavior during Stress

In the following, the ETM will be tested whether it is consistent with the

experimental findings presented in Section 1.4. For this model evaluation, the

temporal behavior during the stress phase is the most essential criterion. It is

depicted in Fig. 4.8 as the evolution of trapped charges  and the threshold

voltage shift

and the threshold

voltage shift  . The former reveals a logarithmic time behavior, which

is preserved for a large time range and by far exceeds the measurement

window ranging from

. The former reveals a logarithmic time behavior, which

is preserved for a large time range and by far exceeds the measurement

window ranging from  to

to  . Recall that the behavior of one defect is

described by the rate equation (4.6), which has the form of an ordinary

first-order differential equation (4.1). It has been pointed out in Section 4.1

that the change in the occupancy

. Recall that the behavior of one defect is

described by the rate equation (4.6), which has the form of an ordinary

first-order differential equation (4.1). It has been pointed out in Section 4.1

that the change in the occupancy  is given by the dominating time

constants in the exponential term of equation (4.2). In the hole trapping

region (cf. Fig. 4.3),

is given by the dominating time

constants in the exponential term of equation (4.2). In the hole trapping

region (cf. Fig. 4.3),  holds. Then equation (4.2) simplifies to

holds. Then equation (4.2) simplifies to

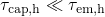

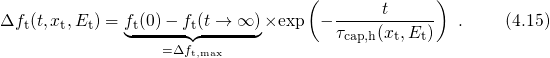

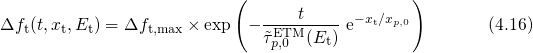

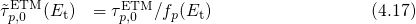

Assuming a rectangular tunneling barrier for the WKB factor, one obtains

using the definitions and The exponential term on the right-hand side of equation (4.16) is characterized by a

sharp drop at which suggests the following approximation The sharp drop at  represents a border between defects which ‘already

have’ and ‘still do not have’ captured holes from the substrate until the

time

represents a border between defects which ‘already

have’ and ‘still do not have’ captured holes from the substrate until the

time  . This border moves away from the substrate towards deep into the

dielectric as time progresses (see Fig. 4.9). Its shift follows a time logarithmic

law according to equation (4.19) and results in straight lines in

. This border moves away from the substrate towards deep into the

dielectric as time progresses (see Fig. 4.9). Its shift follows a time logarithmic

law according to equation (4.19) and results in straight lines in  of

Fig. 4.8. When the border arrives at the gate, hole trapping stops, which

becomes visible as a saturation in

of

Fig. 4.8. When the border arrives at the gate, hole trapping stops, which

becomes visible as a saturation in  and

and  . According to

the charge sheet approximation, charges more distant from the substrate

oxide interface make a smaller contribution to

. According to

the charge sheet approximation, charges more distant from the substrate

oxide interface make a smaller contribution to  due to their smaller

weighting factors

due to their smaller

weighting factors  in equation (3.25). This yields the curvature seen

in

in equation (3.25). This yields the curvature seen

in  plots of Fig. 4.8. However, the resulting curves still roughly

follow a logarithmic time behavior. When disregarding the oxide field and

temperature dependence for the time being, this fact might be misinterpreted as

an agreement with the experimentally observed logarithmic time behavior

(1.8).

plots of Fig. 4.8. However, the resulting curves still roughly

follow a logarithmic time behavior. When disregarding the oxide field and

temperature dependence for the time being, this fact might be misinterpreted as

an agreement with the experimentally observed logarithmic time behavior

(1.8).

4.2.4 Time Range of Trapping

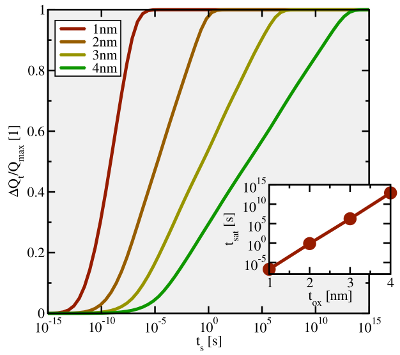

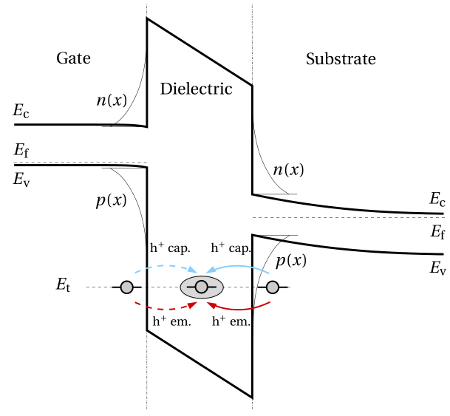

The simulations in Fig. 4.8 reveal that hole trapping sets in around  and lasts

over approximately 15 decades. In this context one should consider that the electrical

characterization methods used in NBTI have a limited time resolution of about

and lasts

over approximately 15 decades. In this context one should consider that the electrical

characterization methods used in NBTI have a limited time resolution of about  .

Therefore, they can only assess the accumulated degradation within a small

measurement window while a large part of the real degradation is invisible in the

experimental data. However, note that despite the wide time range, hole trapping is

limited to a few seconds in a

.

Therefore, they can only assess the accumulated degradation within a small

measurement window while a large part of the real degradation is invisible in the

experimental data. However, note that despite the wide time range, hole trapping is

limited to a few seconds in a  thick device (cf. Fig. 4.10). By contrast, no sign

of saturation has been experimentally observed in the stress phase of NBTI so

far.

thick device (cf. Fig. 4.10). By contrast, no sign

of saturation has been experimentally observed in the stress phase of NBTI so

far.

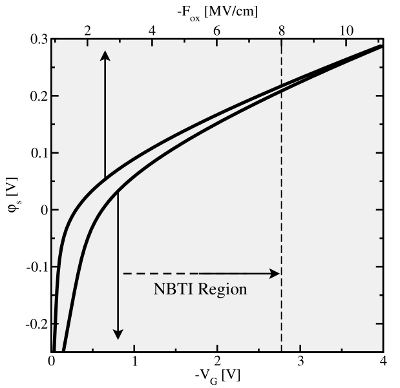

4.2.5 Oxide Field Dependence

The simulated curves in Fig. 4.8 have the same shape irrespective of the applied gate

bias and can be made overlap by multiplying them with appropriate scaling factors

. According to measurement data,

. According to measurement data,  should follow a quadratic

field dependence up to approximately

should follow a quadratic

field dependence up to approximately  . However, the required scaling

factors do not show the correct tendency. Recall that only defects energetically

shifted above

. However, the required scaling

factors do not show the correct tendency. Recall that only defects energetically

shifted above  are capable of capturing holes. Therefore, the amount of

trapped charges per unit time is determined by the difference between

are capable of capturing holes. Therefore, the amount of

trapped charges per unit time is determined by the difference between  and

and

before and during the application of the stress voltage. The relative

shift of these both energies is directly related to the surface potential

before and during the application of the stress voltage. The relative

shift of these both energies is directly related to the surface potential  according to equation (3.9). The simulations in Fig. 4.11 demonstrate that

according to equation (3.9). The simulations in Fig. 4.11 demonstrate that  follows a nearly linear behavior over a wide range of the electric fields. As a

result, one obtains a linear dependence for

follows a nearly linear behavior over a wide range of the electric fields. As a

result, one obtains a linear dependence for  in the NBTI region

(indicated in Fig. 4.11), opposed to the quadratic field-acceleration observed in

experiments.

in the NBTI region

(indicated in Fig. 4.11), opposed to the quadratic field-acceleration observed in

experiments.

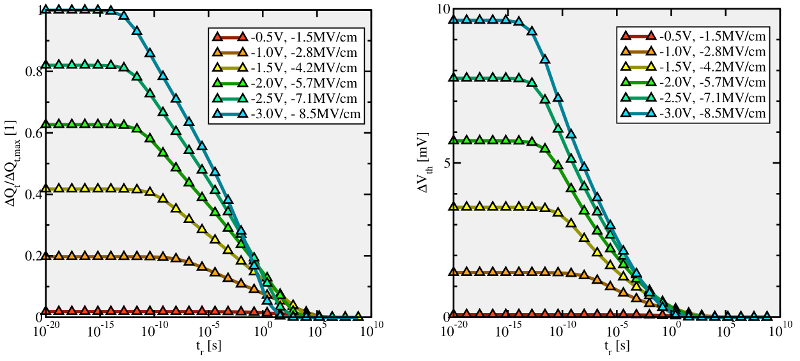

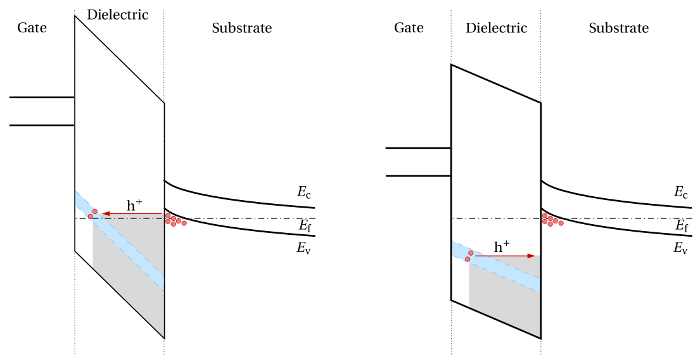

4.2.6 Time Behavior during Relaxation

In the simulated relaxation data in Fig. 4.12, the degradation returns back to its

pre-stress value, meaning that all defects charged during the stress phase also take

part in the recovery phase via hole emission. In these simulations it has been

presumed that the trapped holes can only tunneling back to the substrate. However

in devices with a small oxide thickness, the trapped charges can in principle be

emitted to the poly-gate contact. This case will be addressed in detail in

Section 4.2.8.

The simulations in Fig. 4.12 exhibit a logarithmic time behavior as

observed in experiments (see Section 1.4). As for the stress phase, hole

tunneling is determined by the WKB factor so that the tunneling times

increase exponentially with larger  . This gives rise to a tunneling

electron

front, which starts out from the substrate and continues deep into the dielectric as

illustrated in Fig. 4.13. The annihilation of trapped holes becomes visible as

straight lines in Fig. 4.12, consistent with the experimental findings for

the recovery phase. Against intuition, devices stressed at a higher gate bias

recover faster. This can be traced back to the fact that spatially deeper traps

have a reduced tunneling barrier when they are shifted down in the band

energy diagram during relaxation (see Fig. 4.14). The above behavior has not

been observed in measurements. This deviation from experimental data

could, in principle, also originate from an additional permanent or slowly

recovering component which is not accounted for in the present simulations.

As compared to the stress phase, the time span for the relaxation phase is

shortened for higher gate biases so that the recovery already ends before

. This gives rise to a tunneling

electron

front, which starts out from the substrate and continues deep into the dielectric as

illustrated in Fig. 4.13. The annihilation of trapped holes becomes visible as

straight lines in Fig. 4.12, consistent with the experimental findings for

the recovery phase. Against intuition, devices stressed at a higher gate bias

recover faster. This can be traced back to the fact that spatially deeper traps

have a reduced tunneling barrier when they are shifted down in the band

energy diagram during relaxation (see Fig. 4.14). The above behavior has not

been observed in measurements. This deviation from experimental data

could, in principle, also originate from an additional permanent or slowly

recovering component which is not accounted for in the present simulations.

As compared to the stress phase, the time span for the relaxation phase is

shortened for higher gate biases so that the recovery already ends before

.

.

A remarkable peculiarity of NBTI is the the asymmetry in the slopes during stress

( ) and relaxation (

) and relaxation ( ). It is related to the fact that

the recovery phase exceeds the duration of the stress phase by a couple

of decades. However, the ETM (see Fig. 4.15) predicts that the recovery

proceeds at equal pace or even faster than the degradation during stress

does. This is due to the fact that traps charged with

). It is related to the fact that

the recovery phase exceeds the duration of the stress phase by a couple

of decades. However, the ETM (see Fig. 4.15) predicts that the recovery

proceeds at equal pace or even faster than the degradation during stress

does. This is due to the fact that traps charged with  during stress

emit their holes with approximately the same time constants

during stress

emit their holes with approximately the same time constants  during

recovery.

during

recovery.

4.2.7 Investigation of the Temperature Dependence using a Quantum Refinement

Another important issue concern the temperature dependence of the ETM. Recall

that the experimental data exhibit an increased degradation at higher temperatures,

which was thought to go hand in hand with an enhanced ‘total’ hole concentration

.

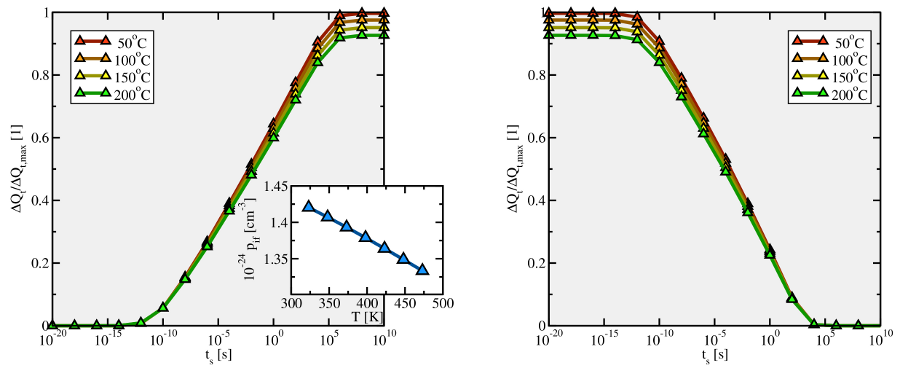

However, the simulations in Fig. 4.16 reveal an inverse tendency for the ETM. The

discrepancy might be attributed to a shift of the hole centroid into the substrate and

an associated reduction in the ‘interfacial’ hole concentration

.

However, the simulations in Fig. 4.16 reveal an inverse tendency for the ETM. The

discrepancy might be attributed to a shift of the hole centroid into the substrate and

an associated reduction in the ‘interfacial’ hole concentration  (see insert of

Fig. 4.16) for higher temperatures. In the band diagram, this is associated with a rise

of

(see insert of

Fig. 4.16) for higher temperatures. In the band diagram, this is associated with a rise

of  towards the center of the substrate bandgap and thus away from

towards the center of the substrate bandgap and thus away from  . The

relative position of

. The

relative position of  and

and  at the interface is the quantity which enters the

calculation of the tunneling rates (2.46) and yields a reduction in the amount of hole

trapping for higher temperatures. In a quantum mechanical treatment, the substrate

holes are described by channel wavefunctions, which are spread over the

whole channel region and penetrate deep into the dielectric. Tunneling and

thus charge trapping are eventually induced by the overlap of the hole and

trap wavefunctions. The ETM must be refined in order to account for the

quantum mechanical nature of the confined charge carriers in the channel.

Again equation (2.34) is taken as a starting point in the following derivation.

at the interface is the quantity which enters the

calculation of the tunneling rates (2.46) and yields a reduction in the amount of hole

trapping for higher temperatures. In a quantum mechanical treatment, the substrate

holes are described by channel wavefunctions, which are spread over the

whole channel region and penetrate deep into the dielectric. Tunneling and

thus charge trapping are eventually induced by the overlap of the hole and

trap wavefunctions. The ETM must be refined in order to account for the

quantum mechanical nature of the confined charge carriers in the channel.

Again equation (2.34) is taken as a starting point in the following derivation.

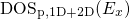

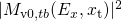

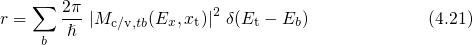

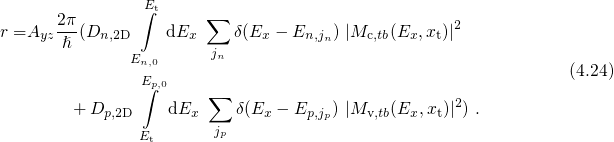

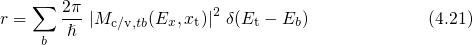

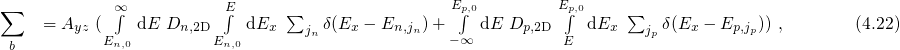

Here,  stands for the initial states. The sum over these states is split into

components parallel and perpendicular to the semiconductor-oxide interface, where

the charge carriers are confined in the latter direction. As derived in the

Appendix A.4, the number of states in an one-dimensional confined electron gas is

stands for the initial states. The sum over these states is split into

components parallel and perpendicular to the semiconductor-oxide interface, where

the charge carriers are confined in the latter direction. As derived in the

Appendix A.4, the number of states in an one-dimensional confined electron gas is

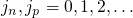

denote the quantum numbers and

denote the quantum numbers and  the respective

eigenstates of the confined states in the conduction or the valence band,

respectively. Note that the integrals run from the first confined eigenstate

the respective

eigenstates of the confined states in the conduction or the valence band,

respectively. Note that the integrals run from the first confined eigenstate

or

or  since they are located closest to the conduction or valence

band edges, respectively. Using (4.22), the rate (4.21) can be rewritten as

Due to the

since they are located closest to the conduction or valence

band edges, respectively. Using (4.22), the rate (4.21) can be rewritten as

Due to the  -function, the right-hand side of equation (4.22) can be simplified to

-function, the right-hand side of equation (4.22) can be simplified to

The refined variant of the ETM shows an increase in the total hole concentration

(see inset of Fig. 4.17), which would suggest an increased degradation for

higher temperatures. Contrary to this ad hoc hypothesis, the simulations in Fig. 4.17

yield a reduced degradation, which is still in contrast to the experimental

observations (see Section 1.4). Actually, not the change in the hole concentration —

may it be

(see inset of Fig. 4.17), which would suggest an increased degradation for

higher temperatures. Contrary to this ad hoc hypothesis, the simulations in Fig. 4.17

yield a reduced degradation, which is still in contrast to the experimental

observations (see Section 1.4). Actually, not the change in the hole concentration —

may it be  or

or  — causes the inverse trend but the shift of

— causes the inverse trend but the shift of  relative to

relative to

. From a statistical point of view, traps and band states at an energy

. From a statistical point of view, traps and band states at an energy  will

equilibrate, meaning that their occupancies

will

equilibrate, meaning that their occupancies  and

and  will equalize. For higher

temperatures, the raise of

will equalize. For higher

temperatures, the raise of  in the band diagram implies a reduction of

in the band diagram implies a reduction of  and in

consequence

and in

consequence  , which is related to the amount of trapped charges. It is important

to note here that the density of states only affects the rates but not the equilibrium

trap occupancies. In conclusion, the inverse temperature dependence cannot

be ascribed to the deficiency of the classical variant of the ETM but it is

inherent to elastic tunneling itself. Furthermore, the curves in Fig. 4.17 are

shifted approximately two decades towards earlier times compared to the

classical variant, which worsens the problem of the early saturation during

stress.

, which is related to the amount of trapped charges. It is important

to note here that the density of states only affects the rates but not the equilibrium

trap occupancies. In conclusion, the inverse temperature dependence cannot

be ascribed to the deficiency of the classical variant of the ETM but it is

inherent to elastic tunneling itself. Furthermore, the curves in Fig. 4.17 are

shifted approximately two decades towards earlier times compared to the

classical variant, which worsens the problem of the early saturation during

stress.

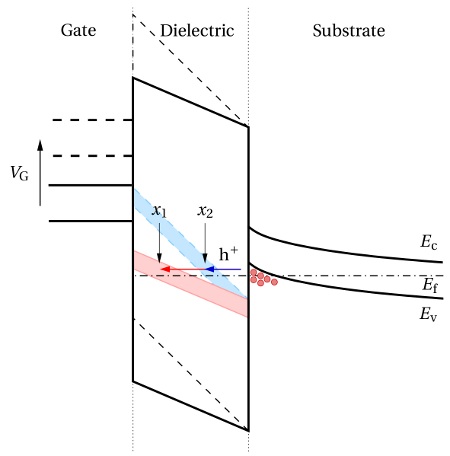

4.2.8 Charge Injection from the Gate

So far, the existing description of charge trapping has been restricted to

charge injection from the substrate. In device structures with thicker gate

dielectrics, the large tunneling distances from the gate towards the defects are

associated with small rates so that the presence of the gate contact as a

source or sink of charge carriers could be neglected. As the oxide thickness

of modern semiconductor devices has entered the nanometer range, this

assumption has lost its justification. Therefore, the ETM needs to be extended

by charge carrier injection from the gate. As illustrated in Fig. 4.18, this

can be achieved by introducing additional terms into the rates equation:

The subscripts  and

and  refer to quantities from the substrate or the poly-gate,

respectively. The simulations presented in Fig. 4.19 underline the importance of the

gate contact when thin dielectrics are considered. Recall that tunneling in the

conventional ETM can be envisaged as a tunneling hole front that starts at the

substrate interface and continues towards the gate. Traps located in the second half

of the dielectric are located closer to the gate and thus have shorter tunneling

distances to the gate. For these traps, electron injection from the gate outbalances

hole trapping from the substrate. Hence, the presence of the gate interface establishes

a spatial border to the penetrating hole front. When this border is reached, the

tunneling hole front stops, which causes an even earlier saturation during the stress

phase. At this point it is important to note that, depending on the spatial and

energetical distribution of traps, the band bending in the gate can also trigger

electron injection from the gate. A comparison of both models is presented in

Fig. 4.19. One may notice that the timescale for trapping is dramatically

reduced in the case of the extended ETM. For devices with relatively thick

gate dielectric of

refer to quantities from the substrate or the poly-gate,

respectively. The simulations presented in Fig. 4.19 underline the importance of the

gate contact when thin dielectrics are considered. Recall that tunneling in the

conventional ETM can be envisaged as a tunneling hole front that starts at the

substrate interface and continues towards the gate. Traps located in the second half

of the dielectric are located closer to the gate and thus have shorter tunneling

distances to the gate. For these traps, electron injection from the gate outbalances

hole trapping from the substrate. Hence, the presence of the gate interface establishes

a spatial border to the penetrating hole front. When this border is reached, the

tunneling hole front stops, which causes an even earlier saturation during the stress

phase. At this point it is important to note that, depending on the spatial and

energetical distribution of traps, the band bending in the gate can also trigger

electron injection from the gate. A comparison of both models is presented in

Fig. 4.19. One may notice that the timescale for trapping is dramatically

reduced in the case of the extended ETM. For devices with relatively thick

gate dielectric of  , the saturation sets in before

, the saturation sets in before  . In technologically

more relevant device structures with a gate dielectrics thinner than

. In technologically

more relevant device structures with a gate dielectrics thinner than  ,

the degradation due to hole trapping ends before

,

the degradation due to hole trapping ends before  and would even be

not assessable with ultra-fast MSM measurements[27]. The fact that only

traps with short tunneling times participate during the stress phase is also

reflected in a fast removal of trapped charges during the relaxation phase.

The complete removal of positive charges during the relaxation phase is

achieved within approximately the same timescales than hole trapping during

stress. By contrast, the relaxation seen in experiments is often described as a

long-lasting process, which exceeds

and would even be

not assessable with ultra-fast MSM measurements[27]. The fact that only

traps with short tunneling times participate during the stress phase is also

reflected in a fast removal of trapped charges during the relaxation phase.

The complete removal of positive charges during the relaxation phase is

achieved within approximately the same timescales than hole trapping during

stress. By contrast, the relaxation seen in experiments is often described as a

long-lasting process, which exceeds  . More importantly, hole trapping is

reduced below five decades for oxide thicknesses below

. More importantly, hole trapping is

reduced below five decades for oxide thicknesses below  while the eMSM

data on a

while the eMSM

data on a  thick device (see Fig. 1.4) show at least seven decades.

thick device (see Fig. 1.4) show at least seven decades.

4.2.9 Width of the Trap Band

Up to this point, only broad distributions of trap levels have been addressed.

However, it is speculated that some high- dielectrics have a crystalline

structure[166], which is characterized by small temperature-induced variations of

bond distances and angles. These lattice distortions yield a small spreading of defect

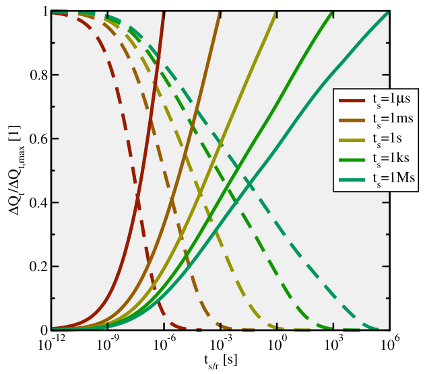

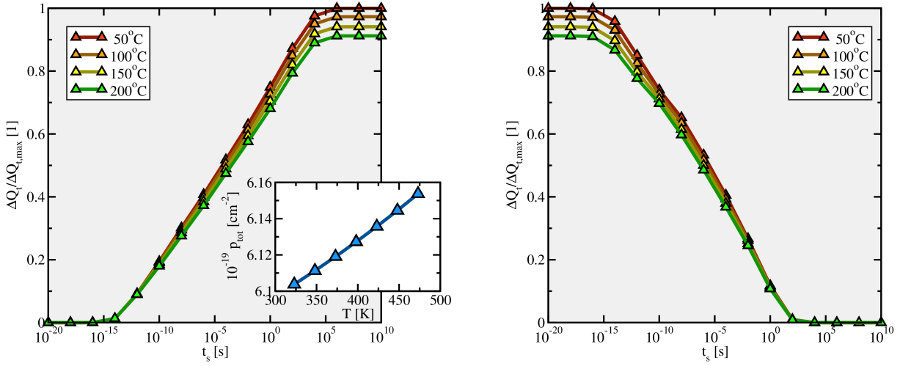

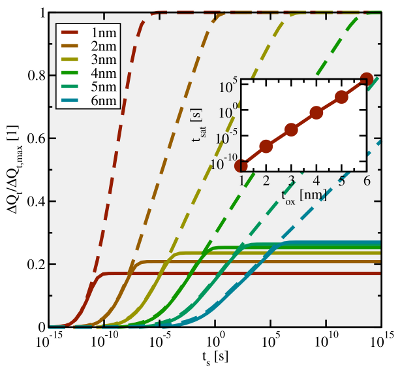

levels, seen as a small trap band in Fig. 4.20. In Fig. 4.20, the time evolution of

dielectrics have a crystalline

structure[166], which is characterized by small temperature-induced variations of

bond distances and angles. These lattice distortions yield a small spreading of defect

levels, seen as a small trap band in Fig. 4.20. In Fig. 4.20, the time evolution of

is plotted for a narrow distribution of defect levels. During stress, the onset of

hole trapping is shifted towards earlier times for increasing gate voltages. This

behavior can be traced back to different defects involved in charge trapping at

different

is plotted for a narrow distribution of defect levels. During stress, the onset of

hole trapping is shifted towards earlier times for increasing gate voltages. This

behavior can be traced back to different defects involved in charge trapping at

different  (see Fig. 4.21). As the gate bias is increased, defects located closer to

the substrate interface are moved into the region around the Fermi level. Due to

their reduced tunneling distances, they feature shorter trapping times and

therefore give rise to an earlier onset in the

(see Fig. 4.21). As the gate bias is increased, defects located closer to

the substrate interface are moved into the region around the Fermi level. Due to

their reduced tunneling distances, they feature shorter trapping times and

therefore give rise to an earlier onset in the  curves. Since the defects

in the active trapping region are spatially concentrated to a small region,

their corresponding tunneling distances are limited to a small range. Thus

the distribution of trapping times is sharply peaked, which becomes visible

as sudden jumps in the

curves. Since the defects

in the active trapping region are spatially concentrated to a small region,

their corresponding tunneling distances are limited to a small range. Thus

the distribution of trapping times is sharply peaked, which becomes visible

as sudden jumps in the  curves of Fig. 4.20. The shape of these

curves is in stark contrast to the wide range of timescales usually involved in

NBTI.

curves of Fig. 4.20. The shape of these

curves is in stark contrast to the wide range of timescales usually involved in

NBTI.

and

and  are given by the equations

(2.45) and (2.46), which already incorporate all elastic tunneling transitions between

one trap and the numerous band states. Due to their analytical complexity, these rate

equations are solved numerically using the numerical iteration scheme presented in

Section 3.2. The used simple first-order partial differential equation reads

are given by the equations

(2.45) and (2.46), which already incorporate all elastic tunneling transitions between

one trap and the numerous band states. Due to their analytical complexity, these rate

equations are solved numerically using the numerical iteration scheme presented in

Section 3.2. The used simple first-order partial differential equation reads

) and hole (

) and hole ( ) occupancy are defined as

) occupancy are defined as

being the Fermi-Dirac distribution. The above rate equation features the

same structure as that of equation (4.1). Therefore, the same mathematical

implications as for the phenomenological model hold true for the ETM.

Furthermore, equation (4.6) covers all four basic transitions illustrated Fig. 4.2 so

that it can be viewed as a comprehensive description of elastic tunneling in

MOSFETs.

being the Fermi-Dirac distribution. The above rate equation features the

same structure as that of equation (4.1). Therefore, the same mathematical

implications as for the phenomenological model hold true for the ETM.

Furthermore, equation (4.6) covers all four basic transitions illustrated Fig. 4.2 so

that it can be viewed as a comprehensive description of elastic tunneling in

MOSFETs.

and

and  in

in

and

and  of equation (

of equation ( and reverse

and reverse  rate considering hole trapping

(

rate considering hole trapping

( ).

). equilibrates to that of

the valence band states at the same energy

equilibrates to that of

the valence band states at the same energy  . For steady state conditions,

. For steady state conditions,  reads

reads

and

and  take the role of

take the role of  and

and  in (4.2), respectively. The

above equation shows that the trap occupancy is eventually governed by the

relative magnitude of

in (4.2), respectively. The

above equation shows that the trap occupancy is eventually governed by the

relative magnitude of  and

and  . Both time constants are most

strongly affected by the exponential decay of the Fermi-Dirac distribution. This

dependence is pointed out in Fig. 4.3, where the hole capture and emission

times are plotted with respect to the trap energy

. Both time constants are most

strongly affected by the exponential decay of the Fermi-Dirac distribution. This

dependence is pointed out in Fig. 4.3, where the hole capture and emission

times are plotted with respect to the trap energy  . In the region below

. In the region below

, the hole occupancy

, the hole occupancy  decreases by several orders of magnitude per

decreases by several orders of magnitude per

so that the hole capture times

so that the hole capture times  by far exceed the corresponding

emission times

by far exceed the corresponding

emission times  . Therefore, no effective hole trapping can take place in

this region, irrespectively of the temperature. By contrast above

. Therefore, no effective hole trapping can take place in

this region, irrespectively of the temperature. By contrast above  , the

exponential decay of

, the

exponential decay of  causes an increase in the hole emission times

causes an increase in the hole emission times  ,

which gives rise to hole trapping there. That is,

,

which gives rise to hole trapping there. That is,  can be regarded as a

demarcation energy between both regions. This fact is also reflected in the

equilibrium solution (4.12) when using the definitions of

can be regarded as a

demarcation energy between both regions. This fact is also reflected in the

equilibrium solution (4.12) when using the definitions of  and

and  .

.

) and emission times (

) and emission times ( ) for two

different temperatures as a function of the trap level

) for two

different temperatures as a function of the trap level  . The simulated device

is subject to heavy stress conditions, at which tunneling ‘through’ the dielectric

actually play a crucial role and should be taken into account. Nevertheless,

. The simulated device

is subject to heavy stress conditions, at which tunneling ‘through’ the dielectric

actually play a crucial role and should be taken into account. Nevertheless,  is set to a high gate voltage for illustration purposes only. The Fermi-Dirac

distribution predicts a decrease in

is set to a high gate voltage for illustration purposes only. The Fermi-Dirac

distribution predicts a decrease in  above

above  , which leads to exponentially

rising

, which leads to exponentially

rising  . Analogously,

. Analogously,  decays and

decays and  rises below the

rises below the  . As a

result,

. As a

result,  is larger than

is larger than  in the region above the

in the region above the  so that hole

trapping can occur there. By contrast, hole trapping is inhibited below

so that hole

trapping can occur there. By contrast, hole trapping is inhibited below  since

since  . For higher temperatures, the exponential decay becomes

weaker, which is reflected in smaller slopes of the

. For higher temperatures, the exponential decay becomes

weaker, which is reflected in smaller slopes of the  and

and  .

.  and

and

, the latter is a function of

, the latter is a function of  and cannot be taken out of the integrals in the

rate expressions (

and cannot be taken out of the integrals in the

rate expressions ( and

and

, the matrix element without the WKB factor, are subject

to small variations so that they weakly affect the tunneling rates. Since

the WKB factor falls off quickly with increasing

, the matrix element without the WKB factor, are subject

to small variations so that they weakly affect the tunneling rates. Since

the WKB factor falls off quickly with increasing  , the integral (

, the integral ( . Therefore, it

makes sense to approximate the rate integral (

. Therefore, it

makes sense to approximate the rate integral ( and define the resulting expression as

and define the resulting expression as  . This new

quantity incorporates the weak dependences on

. This new

quantity incorporates the weak dependences on  while the sensitive factors,

namely

while the sensitive factors,

namely  or

or  and the WKB factor, are separated. Due to the small variations

of

and the WKB factor, are separated. Due to the small variations

of  and

and  ,

,  shows small changes with

shows small changes with

compared to

compared to  and

and  (see Fig.

(see Fig.  as a prefactor of the WKB

factor is approximated as a constant. Using the above definitions, the rate equation

for holes reads:

as a prefactor of the WKB

factor is approximated as a constant. Using the above definitions, the rate equation

for holes reads:

becomes the essential

factor (cf. Fig. 4.6). It shows an exponential decay with increasing trap depth, which

results in a shift of

becomes the essential

factor (cf. Fig. 4.6). It shows an exponential decay with increasing trap depth, which

results in a shift of  and

and  towards larger times (cf. Fig. 4.7). Note that the

energy of the tunneling charge carrier also impacts the WKB factor and the capture

and the emission times. Since the energy dependence of the WKB factor enters

both the capture and the emission times, their relative magnitude remains

unaffected and the above argumentation of

towards larger times (cf. Fig. 4.7). Note that the

energy of the tunneling charge carrier also impacts the WKB factor and the capture

and the emission times. Since the energy dependence of the WKB factor enters

both the capture and the emission times, their relative magnitude remains

unaffected and the above argumentation of  as a demarcation energy remains

valid.

as a demarcation energy remains

valid.

,

,  , the

, the

, and their product for flat band conditions. For better visibility,

all functions are normalized to their maximal values. While

, and their product for flat band conditions. For better visibility,

all functions are normalized to their maximal values. While  and

and  remain within one order of magnitude, the WKB factor

drops significantly. Since only the product of the three quantities enters the

integrand of the rate equation (

remain within one order of magnitude, the WKB factor

drops significantly. Since only the product of the three quantities enters the

integrand of the rate equation ( .

.

as a function of the trap level for different

gate biases. Note that

as a function of the trap level for different

gate biases. Note that  remains within one or two orders of magnitude.

The peaks close to

remains within one or two orders of magnitude.

The peaks close to  can be traced back to a small kinetic energy of the holes

within a classical picture. Quantum mechanically, the amplitude of the channel

wavefunction at the interface is reduced for smaller charge carrier energies. This

results in a decreased overlap of the wavefunction in the matrix element, a

smaller tunneling probability, and ultimately in larger

can be traced back to a small kinetic energy of the holes

within a classical picture. Quantum mechanically, the amplitude of the channel

wavefunction at the interface is reduced for smaller charge carrier energies. This

results in a decreased overlap of the wavefunction in the matrix element, a

smaller tunneling probability, and ultimately in larger  close to the band

edges.

close to the band

edges.

) and emission

(

) and emission

( ) times constants on the trap depths. The more distant the traps

are located from the interface, the larger become

) times constants on the trap depths. The more distant the traps

are located from the interface, the larger become  and

and  .

This can be ascribed to the properties of the WKB factor, which decreases

exponentially with the spatial depth of traps. Hence, the tunneling rates are

reduced but the tunneling times are increased for deeper traps. Note that the

crossing between

.

This can be ascribed to the properties of the WKB factor, which decreases

exponentially with the spatial depth of traps. Hence, the tunneling rates are

reduced but the tunneling times are increased for deeper traps. Note that the

crossing between  and

and  always coincides with

always coincides with  , irrespectively of

the tunneling distance. As a consequence, the energetical border to the trapping

region does not vary with the trap depth.

, irrespectively of

the tunneling distance. As a consequence, the energetical border to the trapping

region does not vary with the trap depth. is situated above

is situated above  , the defect will capture a hole if the defect is initially occupied

by an electron. Vice versa, positively charged defects with

, the defect will capture a hole if the defect is initially occupied

by an electron. Vice versa, positively charged defects with  below

below  will

emit their holes. However, this relationship does not make any statement

about the time point when the tunneling transitions occur. This is solely

given by the respective capture (

will

emit their holes. However, this relationship does not make any statement

about the time point when the tunneling transitions occur. This is solely

given by the respective capture ( ) or emission (

) or emission ( ) time constant.

The actual trapping times are given by the WKB factor, which predicts

increasing capture (

) time constant.

The actual trapping times are given by the WKB factor, which predicts

increasing capture ( ) and emission (

) and emission ( ) times for larger tunneling

distances.

) times for larger tunneling

distances.

. Hence, distributions of energy levels with a spread larger

than

. Hence, distributions of energy levels with a spread larger

than  seem to be unrealistic and must be verified by detailed atomistic

investigations.

seem to be unrealistic and must be verified by detailed atomistic

investigations.

) with a strongly doped p-poly gate (

) with a strongly doped p-poly gate ( ) on

top of a

) on

top of a  thick

thick  layer. The traps in the dielectric are uniformly

distributed in space while their corresponding levels span a range from

layer. The traps in the dielectric are uniformly

distributed in space while their corresponding levels span a range from  to

to  below

below  . The operation temperature is

. The operation temperature is  so that this

value lies in the center of the temperature range relevant for NBTI. For

simplicity, only charge injection from the valence band has been taken into

account. Nevertheless, this does not affect the general findings of the model

discussion.

so that this

value lies in the center of the temperature range relevant for NBTI. For

simplicity, only charge injection from the valence band has been taken into

account. Nevertheless, this does not affect the general findings of the model

discussion.

and the threshold

voltage shift

and the threshold

voltage shift  . The former reveals a logarithmic time behavior, which

is preserved for a large time range and by far exceeds the measurement

window ranging from

. The former reveals a logarithmic time behavior, which

is preserved for a large time range and by far exceeds the measurement

window ranging from  to

to  . Recall that the behavior of one defect is

described by the rate equation (

. Recall that the behavior of one defect is

described by the rate equation ( is given by the dominating time

constants in the exponential term of equation (

is given by the dominating time

constants in the exponential term of equation ( holds. Then equation (

holds. Then equation (

represents a border between defects which ‘already

have’ and ‘still do not have’ captured holes from the substrate until the

time

represents a border between defects which ‘already

have’ and ‘still do not have’ captured holes from the substrate until the

time  . This border moves away from the substrate towards deep into the

dielectric as time progresses (see Fig. 4.9). Its shift follows a time logarithmic

law according to equation (4.19) and results in straight lines in

. This border moves away from the substrate towards deep into the

dielectric as time progresses (see Fig. 4.9). Its shift follows a time logarithmic

law according to equation (4.19) and results in straight lines in  of

Fig. 4.8. When the border arrives at the gate, hole trapping stops, which

becomes visible as a saturation in

of

Fig. 4.8. When the border arrives at the gate, hole trapping stops, which

becomes visible as a saturation in  and

and  . According to

the charge sheet approximation, charges more distant from the substrate

oxide interface make a smaller contribution to

. According to

the charge sheet approximation, charges more distant from the substrate

oxide interface make a smaller contribution to  due to their smaller

weighting factors

due to their smaller

weighting factors  in equation (3.25). This yields the curvature seen

in

in equation (3.25). This yields the curvature seen

in  plots of Fig. 4.8. However, the resulting curves still roughly

follow a logarithmic time behavior. When disregarding the oxide field and

temperature dependence for the time being, this fact might be misinterpreted as

an agreement with the experimentally observed logarithmic time behavior

(1.8).

plots of Fig. 4.8. However, the resulting curves still roughly

follow a logarithmic time behavior. When disregarding the oxide field and

temperature dependence for the time being, this fact might be misinterpreted as

an agreement with the experimentally observed logarithmic time behavior

(1.8).

as a function

of stress time for different gate biases (

as a function

of stress time for different gate biases ( ). Charge trapping occurs

over up to approximately 15 decades and shows a logarithmic time dependence.

The slopes in the plot increase linearly with the oxide field, which cannot

be reconciled with the quadratic field dependence obtained from experiments.

). Charge trapping occurs

over up to approximately 15 decades and shows a logarithmic time dependence.

The slopes in the plot increase linearly with the oxide field, which cannot

be reconciled with the quadratic field dependence obtained from experiments.

for different gate

biases. The resulting curves roughly approximate a logarithmic time dependence

in a small experimental window from

for different gate

biases. The resulting curves roughly approximate a logarithmic time dependence

in a small experimental window from  to

to  .

.

).

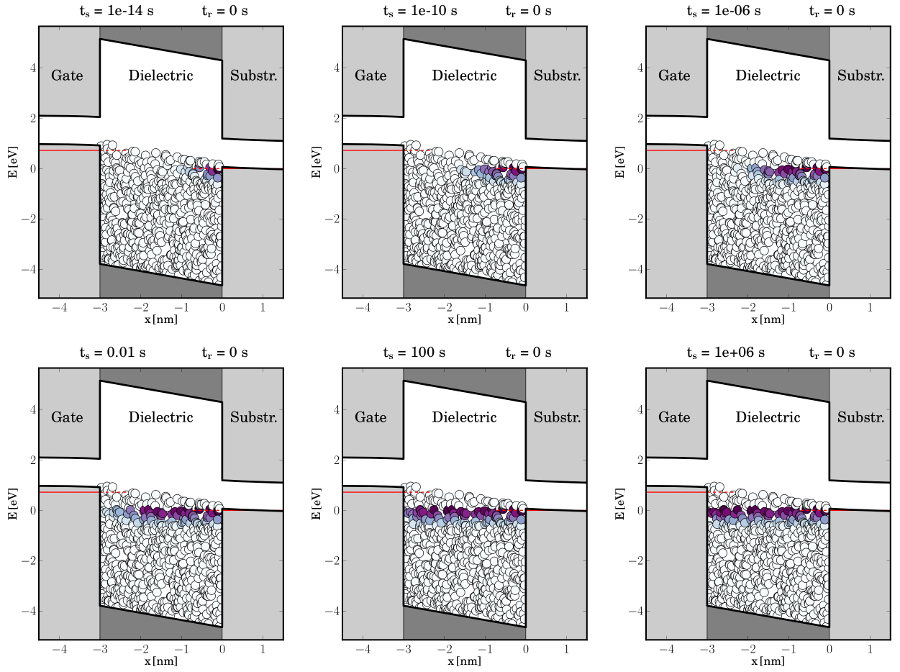

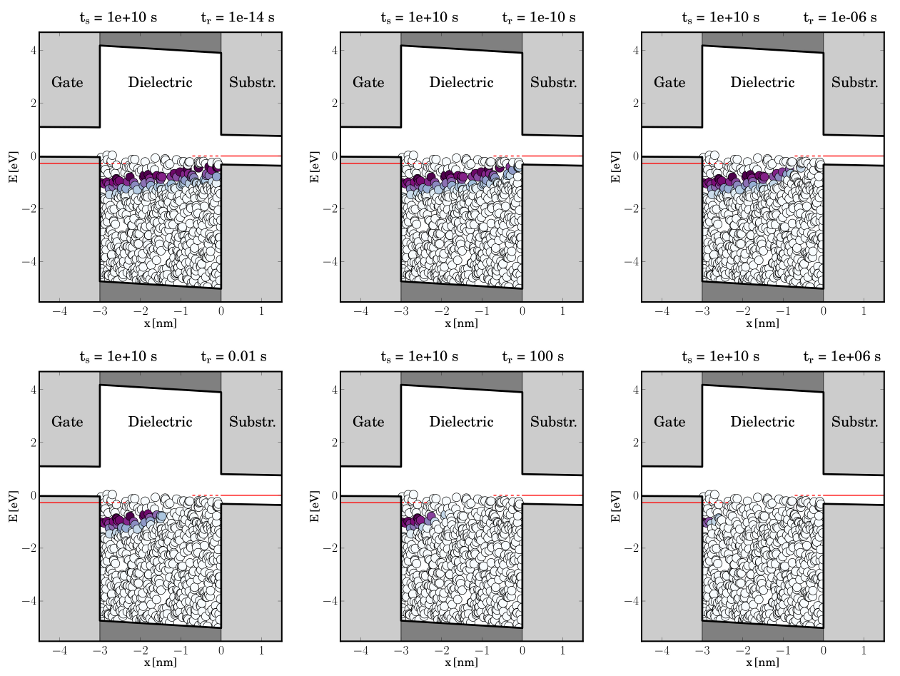

Single traps are represented by the small circles located in the lower part of the

oxide bandgap, where the occupied and the empty states are depicted as purple

and white filled circles, respectively. The hole occupation of traps in the band

diagram is recorded for a series of stress times and demonstrates the filling of

traps with time. One can recognize a tunneling hole front, which starts from

the substrate (right) and penetrates deep into the dielectric (towards the left).

For demonstration purposes, the simulations were performed with the upper

edge of the trap band shifted slightly above the substrate valence band. Note

that traps located above the Fermi level do not have captured holes. This is

due to the fact that these traps are energetically located within the substrate

bandgap and thus have no corresponding energy level which can serve as a hole

source in a tunneling process. Furthermore, hole trapping from the poly-gate

has been neglected in these simulations but this aspect will be addressed later

in Section

).

Single traps are represented by the small circles located in the lower part of the

oxide bandgap, where the occupied and the empty states are depicted as purple

and white filled circles, respectively. The hole occupation of traps in the band

diagram is recorded for a series of stress times and demonstrates the filling of

traps with time. One can recognize a tunneling hole front, which starts from

the substrate (right) and penetrates deep into the dielectric (towards the left).

For demonstration purposes, the simulations were performed with the upper

edge of the trap band shifted slightly above the substrate valence band. Note

that traps located above the Fermi level do not have captured holes. This is

due to the fact that these traps are energetically located within the substrate

bandgap and thus have no corresponding energy level which can serve as a hole

source in a tunneling process. Furthermore, hole trapping from the poly-gate

has been neglected in these simulations but this aspect will be addressed later

in Section  and lasts

over approximately 15 decades. In this context one should consider that the electrical

characterization methods used in NBTI have a limited time resolution of about

and lasts

over approximately 15 decades. In this context one should consider that the electrical

characterization methods used in NBTI have a limited time resolution of about  .

Therefore, they can only assess the accumulated degradation within a small

measurement window while a large part of the real degradation is invisible in the

experimental data. However, note that despite the wide time range, hole trapping is

limited to a few seconds in a

.

Therefore, they can only assess the accumulated degradation within a small

measurement window while a large part of the real degradation is invisible in the

experimental data. However, note that despite the wide time range, hole trapping is

limited to a few seconds in a  thick device (cf. Fig.

thick device (cf. Fig.

,

,  ). For comparison with Section

). For comparison with Section  below the substrate valence

band edge in this simulation. One can observe an early saturation for devices

with an oxide thickness equal or smaller than

below the substrate valence

band edge in this simulation. One can observe an early saturation for devices

with an oxide thickness equal or smaller than  , not seen in experiments.

The inset shows that the time point of saturation is shifted out of the

measurement window for devices with an oxide thickness notably exceeding a

value of

, not seen in experiments.

The inset shows that the time point of saturation is shifted out of the

measurement window for devices with an oxide thickness notably exceeding a

value of  .

.  . According to measurement data,

. According to measurement data,  should follow a quadratic

field dependence up to approximately

should follow a quadratic

field dependence up to approximately  . However, the required scaling

factors do not show the correct tendency. Recall that only defects energetically

shifted above

. However, the required scaling

factors do not show the correct tendency. Recall that only defects energetically

shifted above  are capable of capturing holes. Therefore, the amount of

trapped charges per unit time is determined by the difference between

are capable of capturing holes. Therefore, the amount of

trapped charges per unit time is determined by the difference between  and

and

before and during the application of the stress voltage. The relative

shift of these both energies is directly related to the surface potential

before and during the application of the stress voltage. The relative

shift of these both energies is directly related to the surface potential  according to equation (

according to equation ( follows a nearly linear behavior over a wide range of the electric fields. As a

result, one obtains a linear dependence for

follows a nearly linear behavior over a wide range of the electric fields. As a

result, one obtains a linear dependence for  in the NBTI region

(indicated in Fig.

in the NBTI region

(indicated in Fig.

versus the applied gate bias and

the oxide field for the simulated pMOSFET (

versus the applied gate bias and

the oxide field for the simulated pMOSFET ( ). This quantity is

proportional to the scaling factor

). This quantity is

proportional to the scaling factor  in the simulated curves of Fig.

in the simulated curves of Fig.  shows a nearly linear dependence on the oxide field.

shows a nearly linear dependence on the oxide field.

curve for heavier stress conditions, which shifts

the end of the relaxation phase below

curve for heavier stress conditions, which shifts

the end of the relaxation phase below  .

. . This gives rise to a tunneling

electron

. This gives rise to a tunneling

electron .

.

) and relaxation (

) and relaxation ( ). It is related to the fact that

the recovery phase exceeds the duration of the stress phase by a couple

of decades. However, the ETM (see Fig.

). It is related to the fact that

the recovery phase exceeds the duration of the stress phase by a couple

of decades. However, the ETM (see Fig.  during stress

emit their holes with approximately the same time constants

during stress

emit their holes with approximately the same time constants  during

recovery.

during

recovery.

,

,

) for different stress times. Each pair of curves is normalized to the

last stress value. Note that both curves approximately cover the same number of

decades, which is in disagreement with the experimentally obtained asymmetry

in the slopes during the stress and the relaxation phase.

) for different stress times. Each pair of curves is normalized to the

last stress value. Note that both curves approximately cover the same number of

decades, which is in disagreement with the experimentally obtained asymmetry

in the slopes during the stress and the relaxation phase.

(see insert of

Fig.

(see insert of

Fig.  towards the center of the substrate bandgap and thus away from

towards the center of the substrate bandgap and thus away from  . The

relative position of

. The

relative position of  and

and  at the interface is the quantity which enters the

calculation of the tunneling rates (

at the interface is the quantity which enters the

calculation of the tunneling rates (

stands for the initial states. The sum over these states is split into

components parallel and perpendicular to the semiconductor-oxide interface, where

the charge carriers are confined in the latter direction. As derived in the

Appendix A.4, the number of states in an one-dimensional confined electron gas is

stands for the initial states. The sum over these states is split into

components parallel and perpendicular to the semiconductor-oxide interface, where

the charge carriers are confined in the latter direction. As derived in the

Appendix A.4, the number of states in an one-dimensional confined electron gas is

denote the quantum numbers and

denote the quantum numbers and  the respective

eigenstates of the confined states in the conduction or the valence band,

respectively. Note that the integrals run from the first confined eigenstate

the respective

eigenstates of the confined states in the conduction or the valence band,

respectively. Note that the integrals run from the first confined eigenstate

or

or  since they are located closest to the conduction or valence

band edges, respectively. Using (4.22), the rate (4.21) can be rewritten as

since they are located closest to the conduction or valence

band edges, respectively. Using (4.22), the rate (4.21) can be rewritten as

-function, the right-hand side of equation (4.22) can be simplified to

-function, the right-hand side of equation (4.22) can be simplified to

. Surprisingly, the classical simulations predict a decrease in the

amount of trapped holes for higher temperatures. This seems to be related to

the reduction in the interfacial hole concentration

. Surprisingly, the classical simulations predict a decrease in the

amount of trapped holes for higher temperatures. This seems to be related to

the reduction in the interfacial hole concentration  shown in the insert of

the left plot.

shown in the insert of

the left plot. (see inset of Fig.

(see inset of Fig.  or

or  — causes the inverse trend but the shift of

— causes the inverse trend but the shift of  relative to

relative to

. From a statistical point of view, traps and band states at an energy

. From a statistical point of view, traps and band states at an energy  will

equilibrate, meaning that their occupancies

will

equilibrate, meaning that their occupancies  and

and  will equalize. For higher

temperatures, the raise of

will equalize. For higher

temperatures, the raise of  in the band diagram implies a reduction of

in the band diagram implies a reduction of  and in

consequence

and in

consequence  , which is related to the amount of trapped charges. It is important

to note here that the density of states only affects the rates but not the equilibrium

trap occupancies. In conclusion, the inverse temperature dependence cannot

be ascribed to the deficiency of the classical variant of the ETM but it is

inherent to elastic tunneling itself. Furthermore, the curves in Fig.

, which is related to the amount of trapped charges. It is important

to note here that the density of states only affects the rates but not the equilibrium

trap occupancies. In conclusion, the inverse temperature dependence cannot

be ascribed to the deficiency of the classical variant of the ETM but it is

inherent to elastic tunneling itself. Furthermore, the curves in Fig.

(see the insert of the

left plot) would suggest an increased hole trapping for higher temperatures. In

comparison to the classical variant, a shift of the whole set of curves towards

earlier times is observed.

(see the insert of the

left plot) would suggest an increased hole trapping for higher temperatures. In

comparison to the classical variant, a shift of the whole set of curves towards

earlier times is observed.

and

and  refer to quantities from the substrate or the poly-gate,

respectively. The simulations presented in Fig.

refer to quantities from the substrate or the poly-gate,

respectively. The simulations presented in Fig.  , the saturation sets in before

, the saturation sets in before  . In technologically

more relevant device structures with a gate dielectrics thinner than

. In technologically

more relevant device structures with a gate dielectrics thinner than  ,

the degradation due to hole trapping ends before

,

the degradation due to hole trapping ends before  and would even be

not assessable with ultra-fast MSM measurements

and would even be

not assessable with ultra-fast MSM measurements . More importantly, hole trapping is

reduced below five decades for oxide thicknesses below

. More importantly, hole trapping is

reduced below five decades for oxide thicknesses below  while the eMSM

data on a

while the eMSM

data on a  thick device (see Fig.

thick device (see Fig.

,

,  ). It is

noted that the uppermost trap level is located

). It is

noted that the uppermost trap level is located  below the substrate

valence band edge in this simulation. In the case of the extended ETM, one can

recognize an early saturation, which reflects the stopping of the hole front in

the dielectric. As pointed out in the inset, this time point of saturation is moved

towards an earlier time, which may lie within typical measurement windows for

NBTI (ranging from

below the substrate

valence band edge in this simulation. In the case of the extended ETM, one can

recognize an early saturation, which reflects the stopping of the hole front in

the dielectric. As pointed out in the inset, this time point of saturation is moved

towards an earlier time, which may lie within typical measurement windows for

NBTI (ranging from  to

to  ). One should keep in mind that only devices

with an oxide thickness thicker than

). One should keep in mind that only devices

with an oxide thickness thicker than  show a logarithmic time behavior

beyond

show a logarithmic time behavior

beyond  , which corresponds to the largest investigated stress times.

, which corresponds to the largest investigated stress times. dielectrics have a crystalline

structure

dielectrics have a crystalline

structure is plotted for a narrow distribution of defect levels. During stress, the onset of

hole trapping is shifted towards earlier times for increasing gate voltages. This

behavior can be traced back to different defects involved in charge trapping at

different

is plotted for a narrow distribution of defect levels. During stress, the onset of

hole trapping is shifted towards earlier times for increasing gate voltages. This

behavior can be traced back to different defects involved in charge trapping at

different  (see Fig.

(see Fig.  curves. Since the defects

in the active trapping region are spatially concentrated to a small region,

their corresponding tunneling distances are limited to a small range. Thus

the distribution of trapping times is sharply peaked, which becomes visible

as sudden jumps in the

curves. Since the defects

in the active trapping region are spatially concentrated to a small region,

their corresponding tunneling distances are limited to a small range. Thus

the distribution of trapping times is sharply peaked, which becomes visible

as sudden jumps in the  curves of Fig.

curves of Fig.

(

( ) for

stress (left) and relaxation (right) presuming a narrow distribution of defect

levels (

) for

stress (left) and relaxation (right) presuming a narrow distribution of defect

levels ( ) centered around

) centered around  below the substrate valence band

edge. For this assumption, the ETM predicts short jumps or drops in

below the substrate valence band

edge. For this assumption, the ETM predicts short jumps or drops in  for both phases, which are limited to only a very few decades. This cannot be

reconciled with NBTI data with a relaxation phase that spans over 10 decades.

In the case of

for both phases, which are limited to only a very few decades. This cannot be

reconciled with NBTI data with a relaxation phase that spans over 10 decades.

In the case of  , the defect levels are not moved into the region around

the Fermi level so that no trapping can occur.

, the defect levels are not moved into the region around

the Fermi level so that no trapping can occur.

) where traps with smaller tunneling time constants (

) where traps with smaller tunneling time constants ( ) are

situated. This leads to an earlier onset of charge trapping for higher gate

voltages.

) are

situated. This leads to an earlier onset of charge trapping for higher gate

voltages.