5.2 The Level Shift Model

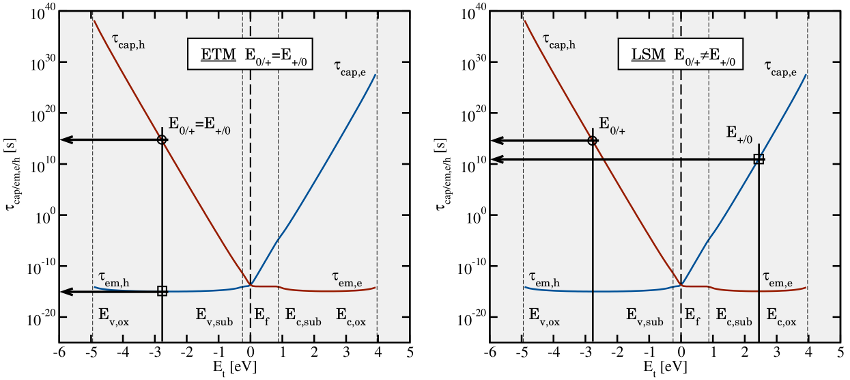

So far, only qualitative statements about the defect behavior could be made based on

the switching levels. In order to make quantitative predictions, the ETM

must be generalized in a way to account for the levels shift. Recall that the

conventional concept of the ETM is based on the assumption that the energy levels

for tunneling ‘into’ and ‘out of’ a defect coincide. This is only the case for

unrealistic defects which do not deform after a tunneling event. But as proven

in the previous Section 5.1, defects do undergo structural relaxation and

therefore feature two switching levels, say  for hole capture and

for hole capture and  for

hole emission for instance, which can even be separated by some electron

Volts (see Fig. 5.9). To be precise, the switching levels

for

hole emission for instance, which can even be separated by some electron

Volts (see Fig. 5.9). To be precise, the switching levels  and

and  actually originate from the one defect orbital and thus must be correctly

interpreted as one trap level, which shifts after each charging or discharging event.

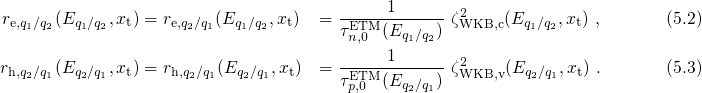

For the trapping kinetics, this means that only one of these levels can be

present in the band diagram at a time. For instance, when the defect in

Fig. 5.10 is in its neutral charge state, it has a trap level

actually originate from the one defect orbital and thus must be correctly

interpreted as one trap level, which shifts after each charging or discharging event.

For the trapping kinetics, this means that only one of these levels can be

present in the band diagram at a time. For instance, when the defect in

Fig. 5.10 is in its neutral charge state, it has a trap level  for hole

capture while its corresponding trap level

for hole

capture while its corresponding trap level  remains inactive for the time

being. If a hole capture process takes place, the

remains inactive for the time

being. If a hole capture process takes place, the  level vanishes and

thus the

level vanishes and

thus the  level appears. Based on the considerations above, the ETM

must be regarded as a special case of the level shift model (LSM) but with a

negligible defect relaxation. Consequently, the formulation of the ETM must be

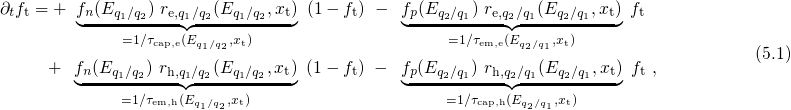

modified in order to account for the level shift. Thus equation (4.6) is rewritten

as

level appears. Based on the considerations above, the ETM

must be regarded as a special case of the level shift model (LSM) but with a

negligible defect relaxation. Consequently, the formulation of the ETM must be

modified in order to account for the level shift. Thus equation (4.6) is rewritten

as

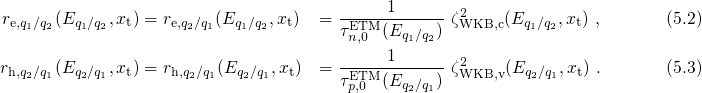

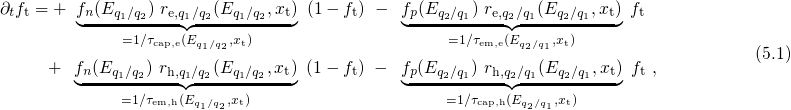

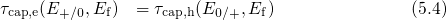

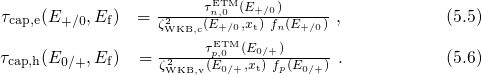

where the rates are defined as

and

and  denote the two charge states involved in the tunneling process and the

trap levels

denote the two charge states involved in the tunneling process and the

trap levels  and

and  corresponds to the switching traps introduced in

Section 2.3. The above rate equation is reminiscent of the ETM presented in the

previous Section 2.5.2. The peculiarity of the LSM is that the particular terms on

the right-hand side of equation (5.1) must be evaluated for different energies, namely

corresponds to the switching traps introduced in

Section 2.3. The above rate equation is reminiscent of the ETM presented in the

previous Section 2.5.2. The peculiarity of the LSM is that the particular terms on

the right-hand side of equation (5.1) must be evaluated for different energies, namely

or

or  , depending on the charge state of the defect before the

tunneling transition occurs. For instance, the positively charged defect of

Fig. 5.9 has a trap level

, depending on the charge state of the defect before the

tunneling transition occurs. For instance, the positively charged defect of

Fig. 5.9 has a trap level  , which must be applied for calculation of the

electron capture rate

, which must be applied for calculation of the

electron capture rate  (see Fig. 5.10). By contrast, the

neutralized defect features a trap level

(see Fig. 5.10). By contrast, the

neutralized defect features a trap level  used for the hole capture rate

used for the hole capture rate

. The calculation of the corresponding time constants is illustrated

in Fig. 5.10. It is important to note here that the expressions for

. The calculation of the corresponding time constants is illustrated

in Fig. 5.10. It is important to note here that the expressions for  ,

,  ,

,

, and

, and  remain the ‘same’ as in the ETM and only change in the

energy they are evaluated for. This is due to the fact that the tunneling

mechanism itself is not affected by the structural relaxation. Thus, analogously to

the ETM, the tunneling process can be described by the tunneling rates

(2.45) and (2.46) of the ETM and reasonably approximated by (5.2) and

(5.3).

remain the ‘same’ as in the ETM and only change in the

energy they are evaluated for. This is due to the fact that the tunneling

mechanism itself is not affected by the structural relaxation. Thus, analogously to

the ETM, the tunneling process can be described by the tunneling rates

(2.45) and (2.46) of the ETM and reasonably approximated by (5.2) and

(5.3).

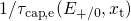

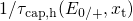

In the following, a new quantity, referred to as the demarcation

energy,

will be introduced. It determines equilibrium occupancy of the defects and is

defined by the condition

will be introduced. It determines equilibrium occupancy of the defects and is

defined by the condition

with

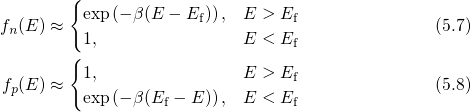

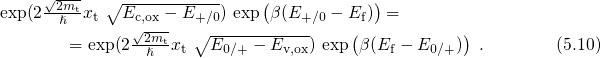

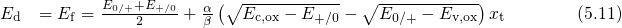

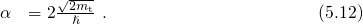

Assuming Boltzmann statistics, the energy dependences of the electron and hole

occupation can be approximated as follows: Suppose that  and

and  as it has been the case for the

as it has been the case for the  center. Then only the exponential terms of

center. Then only the exponential terms of  and

and  enter the time constants.

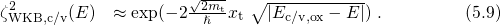

The WKB factors in the expressions (5.5) and (5.6) can be replaced by their

approximative variants for a rectangular barrier. Since

enter the time constants.

The WKB factors in the expressions (5.5) and (5.6) can be replaced by their

approximative variants for a rectangular barrier. Since  holds, equation (5.4) can be

rewritten as Taking the logarithm of this equation and after rearranging some terms, one obtains

with The factor

holds, equation (5.4) can be

rewritten as Taking the logarithm of this equation and after rearranging some terms, one obtains

with The factor  in equation (5.11) takes a value of approximately

in equation (5.11) takes a value of approximately  at

room temperature (

at

room temperature ( ). Thus the last term is negligible compared to the

remainder of equation (5.11) and

). Thus the last term is negligible compared to the

remainder of equation (5.11) and  can be estimated by This quantity predicts the electron occupancy of a defect when equilibrium has been

reached. For instance, when a stress voltage is applied to the gate of a pMOSFET,

can be estimated by This quantity predicts the electron occupancy of a defect when equilibrium has been

reached. For instance, when a stress voltage is applied to the gate of a pMOSFET,

is raised above

is raised above  and the initially neutral defect can capture a substrate hole

during the stress phase. Conversely, when the MOSFET is switched from stress to

relaxation,

and the initially neutral defect can capture a substrate hole

during the stress phase. Conversely, when the MOSFET is switched from stress to

relaxation,  falls below

falls below  and the positively charged defect will become

neutralized in equilibrium. As an example, the

and the positively charged defect will become

neutralized in equilibrium. As an example, the  level of the oxygen vacancy varies

between

level of the oxygen vacancy varies

between  and

and  according to the present DFT results. These values

lie too low to be shifted above

according to the present DFT results. These values

lie too low to be shifted above  for defects located close to the interface

(

for defects located close to the interface

( ). Therefore, the level

). Therefore, the level  of the

of the  center reveals that the LSM is

incompatible with the concept of hole capture into oxygen vacancies. All other

defect candidates, investigated by the DFT simulations in this thesis, feature

values of

center reveals that the LSM is

incompatible with the concept of hole capture into oxygen vacancies. All other

defect candidates, investigated by the DFT simulations in this thesis, feature

values of  close to

close to  and cannot be ruled out on the basis of the above

argument.

and cannot be ruled out on the basis of the above

argument.

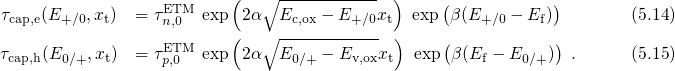

While the equilibrium occupation of the defects is given by the demarcation energy,

the trapping dynamics directly follow from the electron and hole capture time

constants, whose dependence on the Fermi level and the trap depth will be discussed

in the following. The ‘interesting’ instance is when the Fermi level is situated

inbetween the levels  and

and  (cf. Fig. 5.10). Using Boltzmann statistics

(5.7) and (5.8) and approximative WKB factor (5.9), the capture time constants can

be estimated by

(cf. Fig. 5.10). Using Boltzmann statistics

(5.7) and (5.8) and approximative WKB factor (5.9), the capture time constants can

be estimated by

In the equations above, the last term, originating from the Fermi-Dirac distribution,

has the largest impact on both time constants. For instance,  exponentially

depends on the energy difference

exponentially

depends on the energy difference  , that is, a higher

, that is, a higher  level

gives a larger

level

gives a larger  . Analogous considerations hold true for the energy

difference

. Analogous considerations hold true for the energy

difference  and

and  . These dependences are also reflected in the

exponential branches of the time constant plot in Fig. 5.10. Note that the

simulated defect in this figure has been placed only

. These dependences are also reflected in the

exponential branches of the time constant plot in Fig. 5.10. Note that the

simulated defect in this figure has been placed only  away from the

interface where the time taken for the tunnel step can be almost neglected.

However, when the defects are assumed to be situated deeper within the oxide,

their time constants are increased due to the reduced tunnel probability. As

demonstrated in Fig. 5.11 (left), this effect is more pronounced in the middle

of the oxide bandgap while it almost diminishes towards the band edges

due to the reduced tunneling barrier there. The ‘uninteresting’ instance is

when the Fermi level is situated above

away from the

interface where the time taken for the tunnel step can be almost neglected.

However, when the defects are assumed to be situated deeper within the oxide,

their time constants are increased due to the reduced tunnel probability. As

demonstrated in Fig. 5.11 (left), this effect is more pronounced in the middle

of the oxide bandgap while it almost diminishes towards the band edges

due to the reduced tunneling barrier there. The ‘uninteresting’ instance is

when the Fermi level is situated above  as well as

as well as  as shown

Fig. 5.11 (right). In this case

as shown

Fig. 5.11 (right). In this case  is larger than

is larger than  , implying that hole

capture is effectively suppressed. Note that analogous consideration holds

true for the electron capture when the Fermi level fall below

, implying that hole

capture is effectively suppressed. Note that analogous consideration holds

true for the electron capture when the Fermi level fall below  and

and

.

.

5.2.1 Model Evaluation

In this section, the LSM will be employed to investigate the impact of the level

shift on the trapping dynamics in NBTI experiments. Based on the NBTI

checklist established in Section 1.4, it will be tested whether this model is

capable of reproducing the NBTI degradation seen in experiments. The

following simulations are carried out on a pMOSFET ( )

with a strongly doped p-poly gate (

)

with a strongly doped p-poly gate ( ). The thickness of

the oxide layer has been chosen to be

). The thickness of

the oxide layer has been chosen to be  for demonstration purposes.

Thereby, the traps can be homogeneously spread within the dielectric but

are still sufficiently separated (

for demonstration purposes.

Thereby, the traps can be homogeneously spread within the dielectric but

are still sufficiently separated ( ) from the poly interface in order to

be able to neglect trapping from the gate. Furthermore, this wide range

of trap depths ensures a large distribution of capture and emission times

over 14 decades in time (cf. Fig. 5.11). The energy levels of the traps have

been assumed to be uniformly distributed with the

) from the poly interface in order to

be able to neglect trapping from the gate. Furthermore, this wide range

of trap depths ensures a large distribution of capture and emission times

over 14 decades in time (cf. Fig. 5.11). The energy levels of the traps have

been assumed to be uniformly distributed with the  and the

and the  levels being uncorrelated and thus independently calculated using a random

number generator. The operation temperature is set to

levels being uncorrelated and thus independently calculated using a random

number generator. The operation temperature is set to  and thus lies

in the middle of the range relevant for NBTI. It is noted that only charge

injection from the substrate is accounted for in the following simulations for

simplicity.

and thus lies

in the middle of the range relevant for NBTI. It is noted that only charge

injection from the substrate is accounted for in the following simulations for

simplicity.

In the following, the basic properties of the LSM will be discussed on the basis of a

simple showcase. Therefore, this model is evaluated for a type of defect whose trap

level  has a wide distribution below

has a wide distribution below  while the

while the  counterpart

is sharply peaked slightly above

counterpart

is sharply peaked slightly above  (see Fig. 5.12). At the beginning of

the stress phase nearly all defects are neutral and thus occupied by one

electron. In this state, the traps are characterized by the hole capture levels

(see Fig. 5.12). At the beginning of

the stress phase nearly all defects are neutral and thus occupied by one

electron. In this state, the traps are characterized by the hole capture levels

located below the substrate valence band. The corresponding electron

capture levels

located below the substrate valence band. The corresponding electron

capture levels  lie above the substrate conduction band but are inactive

for the time being. During the stress phase, the substrate holes must be

thermally excited to the defect level

lie above the substrate conduction band but are inactive

for the time being. During the stress phase, the substrate holes must be

thermally excited to the defect level  in order that a tunneling process can

occur. In equation (5.6) their energy-dependent concentration is linked to the

factor

in order that a tunneling process can

occur. In equation (5.6) their energy-dependent concentration is linked to the

factor  , which decays exponentially with decreasing energies assuming

Boltzmann statistics. This decay would lead to a temporal filling of traps from

energetically higher towards lower traps in the band diagram. Furthermore, the

tunneling of electrons and holes has an additional trap depth dependence,

which is reflected in the WKB factor of equation (5.6). Analogously to the

ETM, this would cause a temporal filling of traps starting from close to the

interface and continuing deep into the oxide. As demonstrated in Fig. 5.13, the

superposition of both effects results in a tunneling hole front which proceeds

from high defect levels close to the interface towards lower ones deep in the

oxide. The resulting time evolution of the trap occupancies is visualized in

Fig. 5.12.

, which decays exponentially with decreasing energies assuming

Boltzmann statistics. This decay would lead to a temporal filling of traps from

energetically higher towards lower traps in the band diagram. Furthermore, the

tunneling of electrons and holes has an additional trap depth dependence,

which is reflected in the WKB factor of equation (5.6). Analogously to the

ETM, this would cause a temporal filling of traps starting from close to the

interface and continuing deep into the oxide. As demonstrated in Fig. 5.13, the

superposition of both effects results in a tunneling hole front which proceeds

from high defect levels close to the interface towards lower ones deep in the

oxide. The resulting time evolution of the trap occupancies is visualized in

Fig. 5.12.

The temporal filling is also reflected in the occupancies of the demarcation energies,

shown in Fig. 5.14. As already mentioned before, only defects located above  can

participate in hole capture. As a consequence, the temporal filling of traps does

not proceed below

can

participate in hole capture. As a consequence, the temporal filling of traps does

not proceed below  , which thus marks a border to the tunneling hole

front.

, which thus marks a border to the tunneling hole

front.

After the stress phase, a large part of the hole capture levels has disappeared and is

replaced by their corresponding electron capture levels  . The latter

are assumed to be concentrated in a small trap band slightly above the

substrate conduction band. During the recovery phase, electrons in the substrate

conduction band must be thermally excited up to the

. The latter

are assumed to be concentrated in a small trap band slightly above the

substrate conduction band. During the recovery phase, electrons in the substrate

conduction band must be thermally excited up to the  level where

the trap depth-dependent tunneling process can take place. According to

Fig. 5.12, the defects are found to be filled according to their trap depth, visible

as a horizontally moving tunnel front. The small separation of the

level where

the trap depth-dependent tunneling process can take place. According to

Fig. 5.12, the defects are found to be filled according to their trap depth, visible

as a horizontally moving tunnel front. The small separation of the  levels on the energy scale results in a narrow distribution of electron capture

times. From this it follows that two particular charging events at the upper

and the lower edge of the trap band can be hardly resolved in time. As a

consequence, no vertical component in the motion of the tunnel front is observed

during the recovery phase of Fig. 5.12. Analogously to the stress phase, the

tunneling hole front also appears in the occupancies of the demarcation

levels displayed in Fig. 5.14. During the relaxation phase, the

levels on the energy scale results in a narrow distribution of electron capture

times. From this it follows that two particular charging events at the upper

and the lower edge of the trap band can be hardly resolved in time. As a

consequence, no vertical component in the motion of the tunnel front is observed

during the recovery phase of Fig. 5.12. Analogously to the stress phase, the

tunneling hole front also appears in the occupancies of the demarcation

levels displayed in Fig. 5.14. During the relaxation phase, the  levels are

shifted below

levels are

shifted below  where they can be neutralized if equilibrium has been

reached. However, Fig. 5.14 reveals that the discharging of traps has not been

completed even until an unrealistic long relaxation time of

where they can be neutralized if equilibrium has been

reached. However, Fig. 5.14 reveals that the discharging of traps has not been

completed even until an unrealistic long relaxation time of  . It is important

to note here that

. It is important

to note here that  during stress and relaxation determines the active

area in which hole capture is possible. Defects above this area are already

unoccupied before stress and thus cannot capture a further hole, while the

ones below will remain neutral due to the high hole emission rate. As a

result, only defects within this area can change their charge state and thus

contribute to the net amount of captured holes and in further consequence to

NBTI.

during stress and relaxation determines the active

area in which hole capture is possible. Defects above this area are already

unoccupied before stress and thus cannot capture a further hole, while the

ones below will remain neutral due to the high hole emission rate. As a

result, only defects within this area can change their charge state and thus

contribute to the net amount of captured holes and in further consequence to

NBTI.

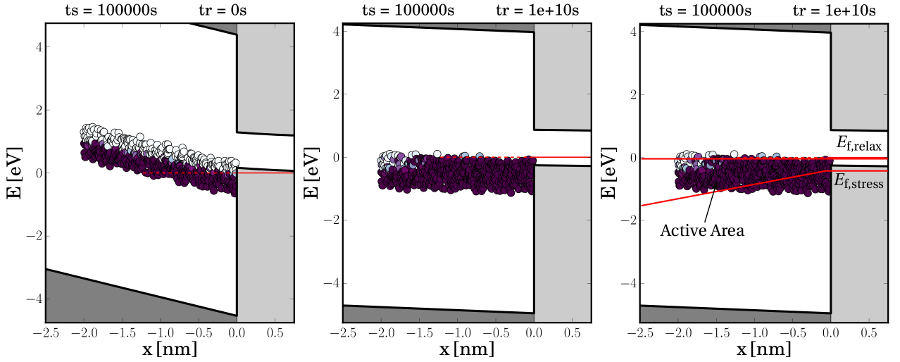

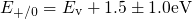

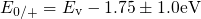

The LSM has been employed to simulate NBTI degradation in a pMOSFET for a

wide range of different stress conditions. The calculated stress/relaxation curves for

the aforementioned showcase are presented in Fig. 5.15. In contrast to the ETM,

they exhibit a marked temperature dependence in addition to the obvious field

acceleration. While the former one mainly stems from the temperature dependent

Fermi-Dirac distribution in  (cf. equation (5.6)), the latter one cannot be

simply interpreted by the lowering of the tunneling barrier at higher

(cf. equation (5.6)), the latter one cannot be

simply interpreted by the lowering of the tunneling barrier at higher  . The

field acceleration originates form the larger shift of the trap levels at higher

. The

field acceleration originates form the larger shift of the trap levels at higher

, as visualized in Fig. 5.16. As such, the field acceleration strongly

depends on the distribution of the trap levels in space and energy but is

not inherent to the LSM itself. For instance, a defect with

, as visualized in Fig. 5.16. As such, the field acceleration strongly

depends on the distribution of the trap levels in space and energy but is

not inherent to the LSM itself. For instance, a defect with  and

and

during stress will not be able to capture a hole at all (see Fig. 5.17).

during stress will not be able to capture a hole at all (see Fig. 5.17).

In order to obtain more realistic results, tunneling from interface states [23] has been

incorporated into LSM. The obtained degradation curves for defects with

and

and  are depicted in Fig. 5.18.

Based on these results, it will be evaluated whether the LSM can satisfactorily

reproduce the basic features seen in NBTI experiments. In the NBTI checklist of

Table 5.2, these features are formulated as necessary criteria, where each of them will

be judged in the following.

are depicted in Fig. 5.18.

Based on these results, it will be evaluated whether the LSM can satisfactorily

reproduce the basic features seen in NBTI experiments. In the NBTI checklist of

Table 5.2, these features are formulated as necessary criteria, where each of them will

be judged in the following.

- Hole trapping during stress and relaxation is found to cover the time range

from milliseconds to a few thousand seconds as in the reference data of

Section 1.4. Moreover, it even extends from

to

to  during stress

and from

during stress

and from  to

to  during relaxation and thus even goes far beyond

the experimental time window.

during relaxation and thus even goes far beyond

the experimental time window.

- At low stress voltages, the degradation curves feature only a weak

curvature and thus roughly follow a logarithmic time behavior.

- Only small deviations from the logarithmic time behavior are present at

low stress voltages in the relaxation phase. But one should kept in mind

that the relaxation data cannot be scaled as there is an intersection point

between the high and low temperature recovery curves.

- Since the degradation accumulated during the stress phase does not

completely recover during the much longer relaxation phase, the LSM

allows for the asymmetry between stress and relaxation. This can be

ascribed to the fact that the

levels are more widely spread on the

energy scale than their

levels are more widely spread on the

energy scale than their  counterparts. The wide separation of the

counterparts. The wide separation of the

levels is linked to a broad distribution of

levels is linked to a broad distribution of  , giving rise to a

retarded recovery.

, giving rise to a

retarded recovery.

- The field acceleration is found to follow a nearly linear behavior (cf.

Fig. 5.19), which is inconsistent with the NBTI criteria of Section 1.4.

- The elevated temperatures yield a weakly enhanced NBTI degradation

during stress (cf. Fig. 5.19), while they reduce the electron capture

times and thus lead to an accelerated recovery during relaxation. These

tendencies cannot be reconciled with the quadratic temperature activation

obtained in experiments.

The above list provides strong evidence that the LSM cannot be reconciled with the

experimental NBTI data. As a consequence, pure tunneling must be discarded as a

possible cause for hole trapping in NBTI.

for hole capture and

for hole capture and  for

hole emission for instance, which can even be separated by some electron

Volts (see Fig. 5.9). To be precise, the switching levels

for

hole emission for instance, which can even be separated by some electron

Volts (see Fig. 5.9). To be precise, the switching levels  and

and  actually originate from the one defect orbital and thus must be correctly

interpreted as one trap level, which shifts after each charging or discharging event.

For the trapping kinetics, this means that only one of these levels can be

present in the band diagram at a time. For instance, when the defect in

Fig. 5.10 is in its neutral charge state, it has a trap level

actually originate from the one defect orbital and thus must be correctly

interpreted as one trap level, which shifts after each charging or discharging event.

For the trapping kinetics, this means that only one of these levels can be

present in the band diagram at a time. For instance, when the defect in

Fig. 5.10 is in its neutral charge state, it has a trap level  for hole

capture while its corresponding trap level

for hole

capture while its corresponding trap level  remains inactive for the time

being. If a hole capture process takes place, the

remains inactive for the time

being. If a hole capture process takes place, the  level vanishes and

thus the

level vanishes and

thus the  level appears. Based on the considerations above, the ETM

must be regarded as a special case of the level shift model (LSM) but with a

negligible defect relaxation. Consequently, the formulation of the ETM must be

modified in order to account for the level shift. Thus equation (4.6) is rewritten

as

level appears. Based on the considerations above, the ETM

must be regarded as a special case of the level shift model (LSM) but with a

negligible defect relaxation. Consequently, the formulation of the ETM must be

modified in order to account for the level shift. Thus equation (4.6) is rewritten

as

and

and  for

electron and hole capture, respectively. When the positively charged trap (blue

filled circle in gray ellipse) captures a substrate electron with an energy of

for

electron and hole capture, respectively. When the positively charged trap (blue

filled circle in gray ellipse) captures a substrate electron with an energy of  (blue arrow), the defect level

(blue arrow), the defect level  vanishes but reappears at

vanishes but reappears at  . The now

neutral defect (red circle in gray ellipse) is only capable of capturing a hole from

the silicon valence band (red arrow). Right after this process the defect level

has returned to its initial position

. The now

neutral defect (red circle in gray ellipse) is only capable of capturing a hole from

the silicon valence band (red arrow). Right after this process the defect level

has returned to its initial position  again.

again.

). The defect is placed close to the interface (

). The defect is placed close to the interface ( ) of a

pMOSFET in the off-state and features one single trap level

) of a

pMOSFET in the off-state and features one single trap level  indicated by the vertical dashed line. In the present case, the trap level lies

indicated by the vertical dashed line. In the present case, the trap level lies

below the substrate valence band edge, where hole emission (circle)

proceeds much faster than hole capture (box). Note that for trap levels within

the substrate bandgap also tunneling from interface states

below the substrate valence band edge, where hole emission (circle)

proceeds much faster than hole capture (box). Note that for trap levels within

the substrate bandgap also tunneling from interface states  at which electron capture time is calculated

has been changed (

at which electron capture time is calculated

has been changed ( ). According to the equations (

). According to the equations ( and

and  are evaluated at two different trap levels, namely one at

are evaluated at two different trap levels, namely one at

for electron capture and another at

for electron capture and another at  for hole capture. For this case

the relative magnitude of

for hole capture. For this case

the relative magnitude of  and

and  depends on the energy distance of

the respective trap level to

depends on the energy distance of

the respective trap level to  .

. and

and  denote the two charge states involved in the tunneling process and the

trap levels

denote the two charge states involved in the tunneling process and the

trap levels  and

and  corresponds to the switching traps introduced in

Section

corresponds to the switching traps introduced in

Section  or

or  , depending on the charge state of the defect before the

tunneling transition occurs. For instance, the positively charged defect of

Fig.

, depending on the charge state of the defect before the

tunneling transition occurs. For instance, the positively charged defect of

Fig.  , which must be applied for calculation of the

electron capture rate

, which must be applied for calculation of the

electron capture rate  (see Fig.

(see Fig.  used for the hole capture rate

used for the hole capture rate

. The calculation of the corresponding time constants is illustrated

in Fig.

. The calculation of the corresponding time constants is illustrated

in Fig.  ,

,  ,

,

, and

, and  remain the ‘same’ as in the ETM and only change in the

energy they are evaluated for. This is due to the fact that the tunneling

mechanism itself is not affected by the structural relaxation. Thus, analogously to

the ETM, the tunneling process can be described by the tunneling rates

(

remain the ‘same’ as in the ETM and only change in the

energy they are evaluated for. This is due to the fact that the tunneling

mechanism itself is not affected by the structural relaxation. Thus, analogously to

the ETM, the tunneling process can be described by the tunneling rates

( will be introduced. It determines equilibrium occupancy of the defects and is

defined by the condition

will be introduced. It determines equilibrium occupancy of the defects and is

defined by the condition

and

and  as it has been the case for the

as it has been the case for the  center. Then only the exponential terms of

center. Then only the exponential terms of  and

and  enter the time constants.

The WKB factors in the expressions (5.5) and (5.6) can be replaced by their

approximative variants for a rectangular barrier.

enter the time constants.

The WKB factors in the expressions (5.5) and (5.6) can be replaced by their

approximative variants for a rectangular barrier.

holds, equation (5.4) can be

rewritten as

holds, equation (5.4) can be

rewritten as

in equation (5.11) takes a value of approximately

in equation (5.11) takes a value of approximately  at

room temperature (

at

room temperature ( ). Thus the last term is negligible compared to the

remainder of equation (5.11) and

). Thus the last term is negligible compared to the

remainder of equation (5.11) and  can be estimated by

can be estimated by

is raised above

is raised above  and the initially neutral defect can capture a substrate hole

during the stress phase. Conversely, when the MOSFET is switched from stress to

relaxation,

and the initially neutral defect can capture a substrate hole

during the stress phase. Conversely, when the MOSFET is switched from stress to

relaxation,  falls below

falls below  and the positively charged defect will become

neutralized in equilibrium. As an example, the

and the positively charged defect will become

neutralized in equilibrium. As an example, the  level of the oxygen vacancy varies

between

level of the oxygen vacancy varies

between  and

and  according to the present DFT results. These values

lie too low to be shifted above

according to the present DFT results. These values

lie too low to be shifted above  for defects located close to the interface

(

for defects located close to the interface

( ). Therefore, the level

). Therefore, the level  of the

of the  center reveals that the LSM is

incompatible with the concept of hole capture into oxygen vacancies. All other

defect candidates, investigated by the DFT simulations in this thesis, feature

values of

center reveals that the LSM is

incompatible with the concept of hole capture into oxygen vacancies. All other

defect candidates, investigated by the DFT simulations in this thesis, feature

values of  close to

close to  and cannot be ruled out on the basis of the above

argument.

and cannot be ruled out on the basis of the above

argument.

and

and  (cf. Fig.

(cf. Fig.

exponentially

depends on the energy difference

exponentially

depends on the energy difference  , that is, a higher

, that is, a higher  level

gives a larger

level

gives a larger  . Analogous considerations hold true for the energy

difference

. Analogous considerations hold true for the energy

difference  and

and  . These dependences are also reflected in the

exponential branches of the time constant plot in Fig. 5.10. Note that the

simulated defect in this figure has been placed only

. These dependences are also reflected in the

exponential branches of the time constant plot in Fig. 5.10. Note that the

simulated defect in this figure has been placed only  away from the

interface where the time taken for the tunnel step can be almost neglected.

However, when the defects are assumed to be situated deeper within the oxide,

their time constants are increased due to the reduced tunnel probability. As

demonstrated in Fig. 5.11 (left), this effect is more pronounced in the middle

of the oxide bandgap while it almost diminishes towards the band edges

due to the reduced tunneling barrier there. The ‘uninteresting’ instance is

when the Fermi level is situated above

away from the

interface where the time taken for the tunnel step can be almost neglected.

However, when the defects are assumed to be situated deeper within the oxide,

their time constants are increased due to the reduced tunnel probability. As

demonstrated in Fig. 5.11 (left), this effect is more pronounced in the middle

of the oxide bandgap while it almost diminishes towards the band edges

due to the reduced tunneling barrier there. The ‘uninteresting’ instance is

when the Fermi level is situated above  as well as

as well as  as shown

Fig. 5.11 (right). In this case

as shown

Fig. 5.11 (right). In this case  is larger than

is larger than  , implying that hole

capture is effectively suppressed. Note that analogous consideration holds

true for the electron capture when the Fermi level fall below

, implying that hole

capture is effectively suppressed. Note that analogous consideration holds

true for the electron capture when the Fermi level fall below  and

and

.

.

,

,  ). The increase in the time constants

is related to a larger tunneling distance for deeper traps. However, this effect,

incorporated in the WKB factor, becomes weaker for energies closer to the oxide

band edges since the tunneling barrier is dramatically lowered there.

). The increase in the time constants

is related to a larger tunneling distance for deeper traps. However, this effect,

incorporated in the WKB factor, becomes weaker for energies closer to the oxide

band edges since the tunneling barrier is dramatically lowered there.  ,

,  ) for the case when the Fermi

level is situated above both trap levels

) for the case when the Fermi

level is situated above both trap levels  and

and  . Since

. Since  exceeds

exceeds

, hole capture is overcompensated by hole emission and thus effectively

suppressed.

, hole capture is overcompensated by hole emission and thus effectively

suppressed. )

with a strongly doped p-poly gate (

)

with a strongly doped p-poly gate ( ). The thickness of

the oxide layer has been chosen to be

). The thickness of

the oxide layer has been chosen to be  for demonstration purposes.

Thereby, the traps can be homogeneously spread within the dielectric but

are still sufficiently separated (

for demonstration purposes.

Thereby, the traps can be homogeneously spread within the dielectric but

are still sufficiently separated ( ) from the poly interface in order to

be able to neglect trapping from the gate. Furthermore, this wide range

of trap depths ensures a large distribution of capture and emission times

over 14 decades in time (cf. Fig.

) from the poly interface in order to

be able to neglect trapping from the gate. Furthermore, this wide range

of trap depths ensures a large distribution of capture and emission times

over 14 decades in time (cf. Fig.  and the

and the  levels being uncorrelated and thus independently calculated using a random

number generator. The operation temperature is set to

levels being uncorrelated and thus independently calculated using a random

number generator. The operation temperature is set to  and thus lies

in the middle of the range relevant for NBTI. It is noted that only charge

injection from the substrate is accounted for in the following simulations for

simplicity.

and thus lies

in the middle of the range relevant for NBTI. It is noted that only charge

injection from the substrate is accounted for in the following simulations for

simplicity.

has a wide distribution below

has a wide distribution below  while the

while the  counterpart

is sharply peaked slightly above

counterpart

is sharply peaked slightly above  (see Fig.

(see Fig.  located below the substrate valence band. The corresponding electron

capture levels

located below the substrate valence band. The corresponding electron

capture levels  lie above the substrate conduction band but are inactive

for the time being. During the stress phase, the substrate holes must be

thermally excited to the defect level

lie above the substrate conduction band but are inactive

for the time being. During the stress phase, the substrate holes must be

thermally excited to the defect level  in order that a tunneling process can

occur. In equation (

in order that a tunneling process can

occur. In equation ( , which decays exponentially with decreasing energies assuming

Boltzmann statistics. This decay would lead to a temporal filling of traps from

energetically higher towards lower traps in the band diagram. Furthermore, the

tunneling of electrons and holes has an additional trap depth dependence,

which is reflected in the WKB factor of equation (

, which decays exponentially with decreasing energies assuming

Boltzmann statistics. This decay would lead to a temporal filling of traps from

energetically higher towards lower traps in the band diagram. Furthermore, the

tunneling of electrons and holes has an additional trap depth dependence,

which is reflected in the WKB factor of equation (

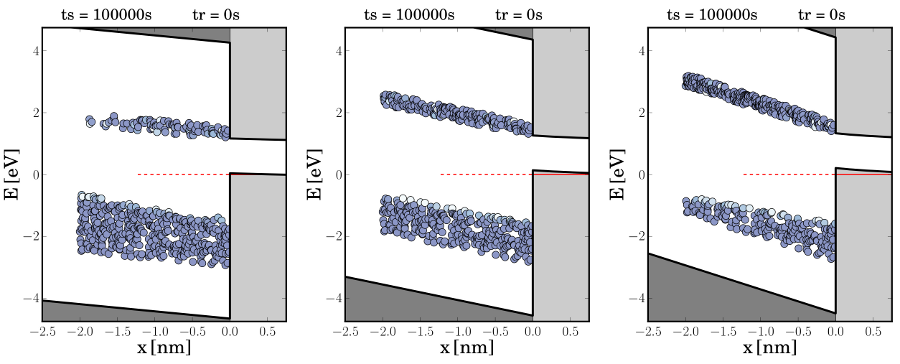

,

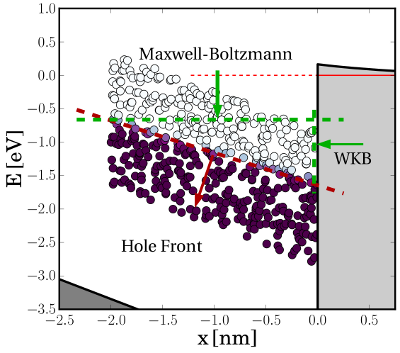

,  ). The

substrate Fermi level is indicated by the red line and the small circles represent

the trap levels

). The

substrate Fermi level is indicated by the red line and the small circles represent

the trap levels  and

and  of the single defects. The neutral defects are

assumed to have fully occupied defect orbitals and thus can only trap holes.

Therefore, they feature hole capture levels

of the single defects. The neutral defects are

assumed to have fully occupied defect orbitals and thus can only trap holes.

Therefore, they feature hole capture levels  , which are located below

the center of the substrate bandgap and are said to be ‘active’. By contrast,

the positively charged defects are assumed to be able to trap electrons only.

Accordingly, they have only electron capture levels

, which are located below

the center of the substrate bandgap and are said to be ‘active’. By contrast,

the positively charged defects are assumed to be able to trap electrons only.

Accordingly, they have only electron capture levels  above midgap but no

energy levels

above midgap but no

energy levels  , which reappear once these defects are charged again. It is

emphasized that the occupancy of one defect is related to which of its trap levels

, which reappear once these defects are charged again. It is

emphasized that the occupancy of one defect is related to which of its trap levels

and

and  is active at the moment. Therefore, the above figures also

reflects the trap occupancies at a certain time. Since the trap levels are recorded

at the beginning, the middle, and the end of the stress and the relaxation phase,

these figures show the tunneling hole front, which is illustrated by the active

trap levels and thus the occupancy of the defects.

is active at the moment. Therefore, the above figures also

reflects the trap occupancies at a certain time. Since the trap levels are recorded

at the beginning, the middle, and the end of the stress and the relaxation phase,

these figures show the tunneling hole front, which is illustrated by the active

trap levels and thus the occupancy of the defects.

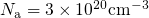

. The capture

time constants are determined by the exponential decay in the WKB factor

and the Fermi-Dirac distribution. The latter has been approximated by the

Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution and shows an exponential energy dependence

a few

. The capture

time constants are determined by the exponential decay in the WKB factor

and the Fermi-Dirac distribution. The latter has been approximated by the

Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution and shows an exponential energy dependence

a few  away from the Fermi level. As indicated by the green vertical arrow,

this dependence leads to a tunneling hole front moving downwards in the band

diagram. By contrast, the WKB factor is most strongly affected by the trap

depth, resulting in an tunneling hole from the substrate to deep into the oxide

(green horizontal arrow). The resulting motion of the tunneling hole front is

depicted by red arrow.

away from the Fermi level. As indicated by the green vertical arrow,

this dependence leads to a tunneling hole front moving downwards in the band

diagram. By contrast, the WKB factor is most strongly affected by the trap

depth, resulting in an tunneling hole from the substrate to deep into the oxide

(green horizontal arrow). The resulting motion of the tunneling hole front is

depicted by red arrow. can

participate in hole capture. As a consequence, the temporal filling of traps does

not proceed below

can

participate in hole capture. As a consequence, the temporal filling of traps does

not proceed below  , which thus marks a border to the tunneling hole

front.

, which thus marks a border to the tunneling hole

front.

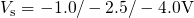

at the end of the stress phase

for the defects shown in Fig.

at the end of the stress phase

for the defects shown in Fig.  ,

,  ). The white

circles represent neutral defects which have not trapped a hole during the stress

phase. The purple filling color indicates that the defect is positively charged

due to a finished hole capture event. Since there exist neutral defects with an

). The white

circles represent neutral defects which have not trapped a hole during the stress

phase. The purple filling color indicates that the defect is positively charged

due to a finished hole capture event. Since there exist neutral defects with an

level above

level above  , hole trapping has not reached saturation after a stress

period lasting

, hole trapping has not reached saturation after a stress

period lasting  .

.  .

.  ) and relaxation (

) and relaxation ( ). The defects situated

below

). The defects situated

below  cannot capture a hole during stress while those located above

cannot capture a hole during stress while those located above

remain positively charged during relaxation and thus do not contribute

to

remain positively charged during relaxation and thus do not contribute

to  .

. . The latter

are assumed to be concentrated in a small trap band slightly above the

substrate conduction band. During the recovery phase, electrons in the substrate

conduction band must be thermally excited up to the

. The latter

are assumed to be concentrated in a small trap band slightly above the

substrate conduction band. During the recovery phase, electrons in the substrate

conduction band must be thermally excited up to the  level where

the trap depth-dependent tunneling process can take place. According to

Fig.

level where

the trap depth-dependent tunneling process can take place. According to

Fig.  levels on the energy scale results in a narrow distribution of electron capture

times. From this it follows that two particular charging events at the upper

and the lower edge of the trap band can be hardly resolved in time. As a

consequence, no vertical component in the motion of the tunnel front is observed

during the recovery phase of Fig.

levels on the energy scale results in a narrow distribution of electron capture

times. From this it follows that two particular charging events at the upper

and the lower edge of the trap band can be hardly resolved in time. As a

consequence, no vertical component in the motion of the tunnel front is observed

during the recovery phase of Fig.  levels are

shifted below

levels are

shifted below  where they can be neutralized if equilibrium has been

reached. However, Fig.

where they can be neutralized if equilibrium has been

reached. However, Fig.  . It is important

to note here that

. It is important

to note here that  during stress and relaxation determines the active

area in which hole capture is possible. Defects above this area are already

unoccupied before stress and thus cannot capture a further hole, while the

ones below will remain neutral due to the high hole emission rate. As a

result, only defects within this area can change their charge state and thus

contribute to the net amount of captured holes and in further consequence to

NBTI.

during stress and relaxation determines the active

area in which hole capture is possible. Defects above this area are already

unoccupied before stress and thus cannot capture a further hole, while the

ones below will remain neutral due to the high hole emission rate. As a

result, only defects within this area can change their charge state and thus

contribute to the net amount of captured holes and in further consequence to

NBTI.

(cf. equation (

(cf. equation ( . The

field acceleration originates form the larger shift of the trap levels at higher

. The

field acceleration originates form the larger shift of the trap levels at higher

, as visualized in Fig.

, as visualized in Fig.  and

and

during stress will not be able to capture a hole at all (see Fig.

during stress will not be able to capture a hole at all (see Fig.

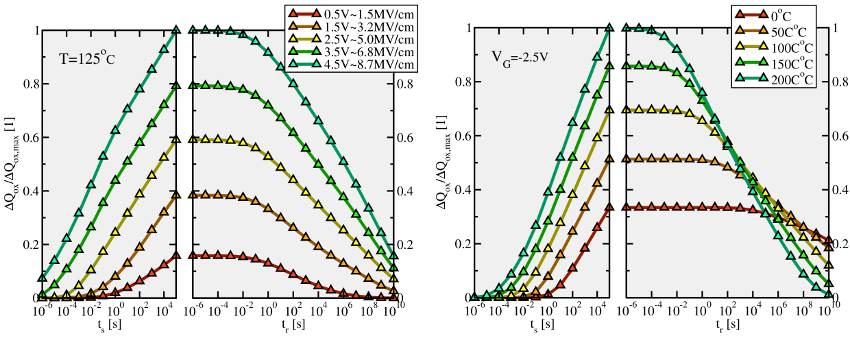

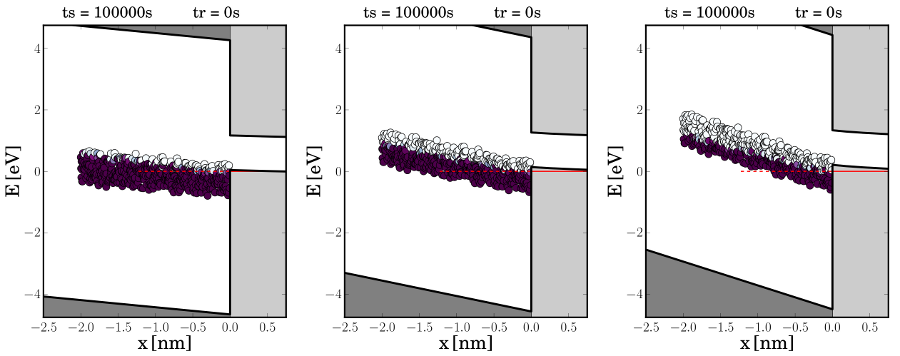

as a function of stress time

for different gate biases.

as a function of stress time

for different gate biases.

and

and  (both second row) after a

stress time of

(both second row) after a

stress time of  for

for  (from left to right) and

(from left to right) and

. The higher position of the

. The higher position of the  levels goes hand in hand with

shorter hole capture times and in consequence a larger amount of trapped

charges after a stress time of

levels goes hand in hand with

shorter hole capture times and in consequence a larger amount of trapped

charges after a stress time of  . From this it can be concluded that the oxide

field dependence of the LSM primarily originates from the upwards shift of the

trap levels but is only marginally influenced by the reduced tunneling barrier

at higher

. From this it can be concluded that the oxide

field dependence of the LSM primarily originates from the upwards shift of the

trap levels but is only marginally influenced by the reduced tunneling barrier

at higher  .

.

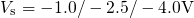

after a stress time

of

after a stress time

of  for

for  (from left to right) and

(from left to right) and  . It

can be recognized that a higher

. It

can be recognized that a higher  increases the portion of

increases the portion of  levels above

levels above

and thus a larger number of traps are available for hole capture.

and thus a larger number of traps are available for hole capture. and

and  are depicted in Fig.

are depicted in Fig.  to

to  during stress

and from

during stress

and from  to

to  during relaxation and thus even goes far beyond

the experimental time window.

during relaxation and thus even goes far beyond

the experimental time window.

levels are more widely spread on the

energy scale than their

levels are more widely spread on the

energy scale than their  counterparts. The wide separation of the

counterparts. The wide separation of the

levels is linked to a broad distribution of

levels is linked to a broad distribution of  , giving rise to a

retarded recovery.

, giving rise to a

retarded recovery.

) when smaller biases are applied to the gate. The

degradation curves follow a nearly logarithmic behavior over a wide time range,

where the curves obtained for a small stress voltages can be better approximated

by a power-law. Furthermore, none of the curves show a sign of saturation until

a stress time of

) when smaller biases are applied to the gate. The

degradation curves follow a nearly logarithmic behavior over a wide time range,

where the curves obtained for a small stress voltages can be better approximated

by a power-law. Furthermore, none of the curves show a sign of saturation until

a stress time of  . It is noted that their slopes appear to be insensitive

to the applied gate bias — except from small gate biases again. Regarding

the relaxation phase, deviations from the time logarithmic behavior can be

recognized below

. It is noted that their slopes appear to be insensitive

to the applied gate bias — except from small gate biases again. Regarding

the relaxation phase, deviations from the time logarithmic behavior can be

recognized below  .

.

and

and

demonstrate that the LSM does not reproduce the quadratic field and

temperature dependence seen in experiments.

demonstrate that the LSM does not reproduce the quadratic field and

temperature dependence seen in experiments.