and

and  will be

derived analytically in the following. The time constants observed in TDDS can be

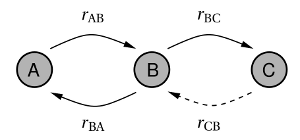

calculated on the basis of first passage times of a two-step process (see Fig. 7.5).

will be

derived analytically in the following. The time constants observed in TDDS can be

calculated on the basis of first passage times of a two-step process (see Fig. 7.5).

In order to promote the understanding of the eNMP model,  and

and  will be

derived analytically in the following. The time constants observed in TDDS can be

calculated on the basis of first passage times of a two-step process (see Fig. 7.5).

will be

derived analytically in the following. The time constants observed in TDDS can be

calculated on the basis of first passage times of a two-step process (see Fig. 7.5).

, provided that it was in the state

, provided that it was in the state  but not in

state B at the beginning. In the eNMP model, one is only interested in the

transition times between the stable states

but not in

state B at the beginning. In the eNMP model, one is only interested in the

transition times between the stable states  and

and  , in which the defect dwells

most of the time. Since the metastable states

, in which the defect dwells

most of the time. Since the metastable states  and

and  are energetically

higher than their corresponding stable counterparts

are energetically

higher than their corresponding stable counterparts  and

and  , the defect

only remains temporarily in these metastable states. This is in agreement

with the condition for the first passage time that the system must not be

in state B at the beginning. As a result, the transition rates between the

states

, the defect

only remains temporarily in these metastable states. This is in agreement

with the condition for the first passage time that the system must not be

in state B at the beginning. As a result, the transition rates between the

states  and

and  can be reasonably described as the inverse of first passage

times.

can be reasonably described as the inverse of first passage

times.

to

to

. The first passage time of such a process is calculated by equation (7.52).

Consider that the transition rate

. The first passage time of such a process is calculated by equation (7.52).

Consider that the transition rate  , indicated by the dashed arrow, does

not enter this equation.

, indicated by the dashed arrow, does

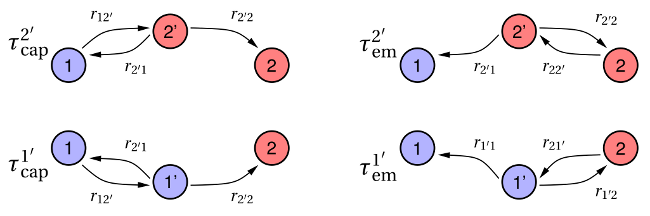

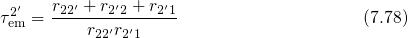

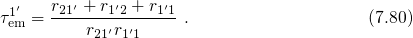

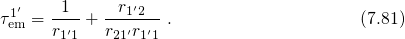

not enter this equation.The various transition pathways allowed in the eNMP model are summarized in the state diagrams of Fig. 7.6. The corresponding first passage times for the hole capture or emission read

and

and  . The superscript of

. The superscript of  denotes the intermediate

state, which has been passed through during a complete capture or the emission

event. Note that there exist two competing pathways for a hole capture event,

namely one over the intermediate state

denotes the intermediate

state, which has been passed through during a complete capture or the emission

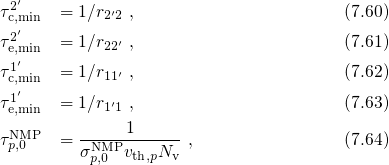

event. Note that there exist two competing pathways for a hole capture event,

namely one over the intermediate state  and one over

and one over  . Of course, the

same holds true for a hole emission event.

. Of course, the

same holds true for a hole emission event.For studying the field dependence of these capture and emission times, the definition

( ) is used for

) is used for  and

and  in the expression for the NMP barriers (7.17):

in the expression for the NMP barriers (7.17):

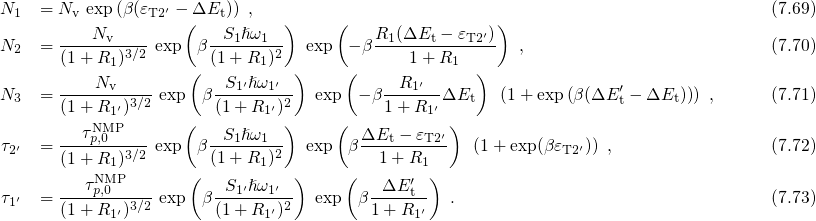

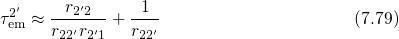

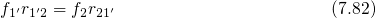

Recall that the hole capture process can proceed from state  over one of the

metastable states

over one of the

metastable states  or

or  to the final state

to the final state  according to the state diagram of

Fig. 7.3. The corresponding capture time constants are denoted as

according to the state diagram of

Fig. 7.3. The corresponding capture time constants are denoted as  and

and  ,

respectively, and will be discussed in the following. When the transition pathway

,

respectively, and will be discussed in the following. When the transition pathway

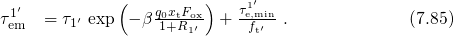

is preferred, the capture time constant in the form of (7.52) is given by

is preferred, the capture time constant in the form of (7.52) is given by

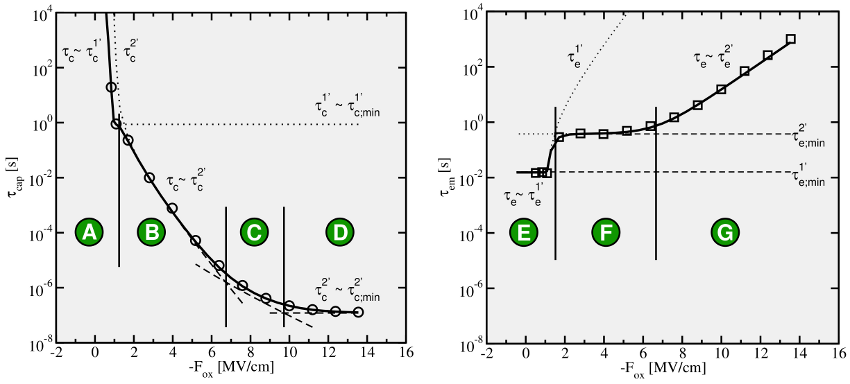

is

characterized by three distinct regimes, namely B, C, and D in Fig. 7.7.

is

characterized by three distinct regimes, namely B, C, and D in Fig. 7.7.

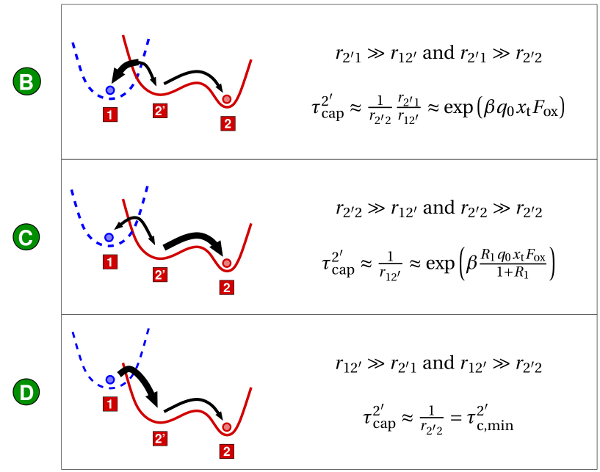

is the dominant

rate meaning that the transition2

is the dominant

rate meaning that the transition2

proceeds much faster than

proceeds much faster than  (cf. Fig. 7.8). Thus the pace

of the complete capture process (

(cf. Fig. 7.8). Thus the pace

of the complete capture process ( ) is determined by the second

transition

) is determined by the second

transition  , which is much slower and has a time constant of

, which is much slower and has a time constant of  .

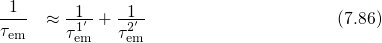

Since this second step is only thermally-activated,

.

Since this second step is only thermally-activated,  does not depend

on the oxide field. This is consistent with equation (7.65) at extremely high

negative oxide fields, at which both exponential terms become negligible

compared to

does not depend

on the oxide field. This is consistent with equation (7.65) at extremely high

negative oxide fields, at which both exponential terms become negligible

compared to  .

.

approaches the

order of magnitude of

approaches the

order of magnitude of  and even falls below

and even falls below  . Then the transition

. Then the transition

over the thermal barrier

over the thermal barrier  is undergone immediately after the

defect has changed from the state

is undergone immediately after the

defect has changed from the state  to

to  . Thus the kinetics of the

hole capture process are governed by the forward rate of the NMP process

. Thus the kinetics of the

hole capture process are governed by the forward rate of the NMP process

. As a result,

. As a result,  shows an exponential oxide field dependence,

which is reflected in the first term of equation (7.65). Note that the second

term is negligible due to its steeper exponential slope within this regime.

shows an exponential oxide field dependence,

which is reflected in the first term of equation (7.65). Note that the second

term is negligible due to its steeper exponential slope within this regime.

is already outbalanced by

its reverse rate

is already outbalanced by

its reverse rate  (see Fig. 7.8) and the ratio of both rates determines

the oxide field dependence. This gives an increased exponential slope

originating from the second term of equation (7.65).

(see Fig. 7.8) and the ratio of both rates determines

the oxide field dependence. This gives an increased exponential slope

originating from the second term of equation (7.65).The transitions between these three regimes are smooth so that a curvature appears

in the time constant plots of  .

.

(A, B, C, and D) are separated by

the thin vertical lines and labeled by the green circles with the capital letters.

The dotted curves

(A, B, C, and D) are separated by

the thin vertical lines and labeled by the green circles with the capital letters.

The dotted curves  show the capture processes over a metastable state

show the capture processes over a metastable state  .

The field dependence of

.

The field dependence of  within a certain regime is shown by the dashed

curve, which becomes constant if

within a certain regime is shown by the dashed

curve, which becomes constant if  is insensitive to

is insensitive to  . Right: The same

but for the hole emission time constants with the regimes (E, F, and G).

. Right: The same

but for the hole emission time constants with the regimes (E, F, and G).

. With higher oxide fields (B

. With higher oxide fields (B  D) the blue potential (neutral

defect) is raised relative to the red one (positive defect). This is associated with

an increase of

D) the blue potential (neutral

defect) is raised relative to the red one (positive defect). This is associated with

an increase of  and a decrease of the reverse rate

and a decrease of the reverse rate  . In contrast to the

charge transfer reactions

. In contrast to the

charge transfer reactions  and

and  , the thermal transition

, the thermal transition  is

not affected by the oxide field.

is

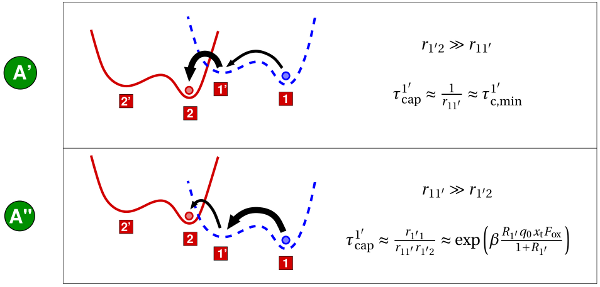

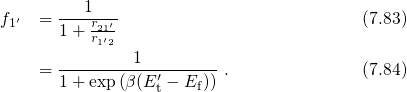

not affected by the oxide field.However, when the transition over the metastable state  is favored (regime A),

the capture time constant can be again formulated as a first passage time:

is favored (regime A),

the capture time constant can be again formulated as a first passage time:

is situated above the state

is situated above the state  by definition,

by definition,

holds. Therefore, the expression (7.75) can be approximated by

which is characterized by only two regimes (A’ and A”) now.

holds. Therefore, the expression (7.75) can be approximated by

which is characterized by only two regimes (A’ and A”) now.

is located relatively high

(see Fig. 7.9) and the transition rate

is located relatively high

(see Fig. 7.9) and the transition rate  exceeds

exceeds  . Therefore, the

first term of expression (7.76) vanishes and the field-insensitive transition

. Therefore, the

first term of expression (7.76) vanishes and the field-insensitive transition

with a time constant of

with a time constant of  dominates

dominates  .

.

is shifted downwards in the

configuration coordinate diagram, thereby decreasing the transition rate

is shifted downwards in the

configuration coordinate diagram, thereby decreasing the transition rate

. At a certain oxide field,

. At a certain oxide field,  falls below

falls below  and the first term of

the expression (7.76) becomes dominant (regime A”). As a consequence,

and the first term of

the expression (7.76) becomes dominant (regime A”). As a consequence,

governed by the field-dependent transition

governed by the field-dependent transition  , which causes

the exponential term of the expression (7.66). Depending on the value of

, which causes

the exponential term of the expression (7.66). Depending on the value of

, there exists a crossing point between the curves

, there exists a crossing point between the curves  and

and  ,

marking the transition between the regime A and B. It is noted that the

NMP transitions in the regimes A, B, and C also involve a nearly negligible

,

marking the transition between the regime A and B. It is noted that the

NMP transitions in the regimes A, B, and C also involve a nearly negligible

field dependence, which has already been present in the TSM for

instance.

field dependence, which has already been present in the TSM for

instance.The transition between A’ and A” yields a kink, which is visible in  of Fig. 7.7 (dotted line) but not in the overall hole capture time given by

of Fig. 7.7 (dotted line) but not in the overall hole capture time given by

.

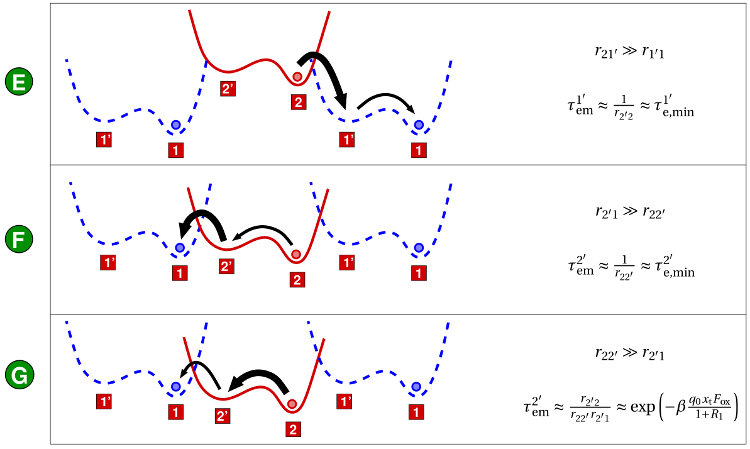

.Also the hole emission process has the possibility to proceed over either the state  or

or  , with

, with  and

and  being the corresponding emission time constants (see

Fig. 7.10). For the transition pathway over

being the corresponding emission time constants (see

Fig. 7.10). For the transition pathway over  the emission time constant can be

expressed as:

the emission time constant can be

expressed as:

applies,

applies,  has only two regimes, labeled with the capital letters

F and G in Fig. 7.7.

has only two regimes, labeled with the capital letters

F and G in Fig. 7.7.

is shifted

upwards so that

is shifted

upwards so that  dominates and the field-dependent NMP transition

dominates and the field-dependent NMP transition

determines the pace of

determines the pace of  . The sensitivity of

. The sensitivity of  to

the oxide field is reflected in the exponential term of equation (7.67).

to

the oxide field is reflected in the exponential term of equation (7.67).

proceeds

much faster than

proceeds

much faster than  over the purely thermal barrier

over the purely thermal barrier  . Thus,

. Thus,

is determined by the field-insensitive transition

is determined by the field-insensitive transition  with a time

constant of

with a time

constant of  . It is important to note that the field independence

of this regime is experimentally observed in the time constant plots of

‘normal’ defects (cf. Fig. 7.4 left).

. It is important to note that the field independence

of this regime is experimentally observed in the time constant plots of

‘normal’ defects (cf. Fig. 7.4 left).

.

.At a low oxide field (regime E), the state  is further shifted down, which

speeds up the NMP transition

is further shifted down, which

speeds up the NMP transition  and allows the pathway over the

metastable state

and allows the pathway over the

metastable state  . The corresponding emission time constant

. The corresponding emission time constant  is given by

is given by

the rate

the rate  is negligible compared to

is negligible compared to  and

and

and the above equation simplifies to

and the above equation simplifies to

and

and  and is marginally disturbed by the rate

and is marginally disturbed by the rate  . Then the states

. Then the states  and

and  can be assumed to be in quasi-equilibrium.

can be assumed to be in quasi-equilibrium.

holds so that the trap occupancy

holds so that the trap occupancy

is given by

is given by

is

equivalent to

is

equivalent to  . Furthermore, this equation can be used to simplify the

equation (7.68) as follows:

. Furthermore, this equation can be used to simplify the

equation (7.68) as follows:

falls below

falls below  at a certain relaxation voltage, the state

at a certain relaxation voltage, the state  becomes occupied

and the emission time

becomes occupied

and the emission time  is determined by the field-independent transition

is determined by the field-independent transition  with the time constant

with the time constant  . By contrast, if

. By contrast, if  is raised above

is raised above  , the state

, the state  is underpopulated thereby slowing down the hole emission process. This occupancy

effect is reflected in the second term, which reacts sensitive to changes in

is underpopulated thereby slowing down the hole emission process. This occupancy

effect is reflected in the second term, which reacts sensitive to changes in

.

.

The overall hole emission time  follows from

follows from

is shifted

below state

is shifted

below state  ,

,  reaches its minimum value and falls below

reaches its minimum value and falls below  . The resulting

drop in

. The resulting

drop in  is observed as the field dependence characterizing ‘anomalous’ defects

at weak oxide fields in TDDS experiments. As pointed out in Fig. 7.4, the

drop of

is observed as the field dependence characterizing ‘anomalous’ defects

at weak oxide fields in TDDS experiments. As pointed out in Fig. 7.4, the

drop of  occurs when the minimum of the state

occurs when the minimum of the state  passes that of state

passes that of state

, and is thus related to the exact shape of the configuration coordinate

diagram.

, and is thus related to the exact shape of the configuration coordinate

diagram.